Chemistry:Methylphenidate

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌmɛθəlˈfɛnɪdeɪt, -ˈfiː-/ |

| Trade names | Ritalin, Concerta, others |

| Other names | MPH[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682188 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | High[2] |

| Addiction liability | High[3] |

| Routes of administration | Insufflation, intravenous, oral, rectal, sublingual, transdermal[2] |

| Drug class | Central nervous system stimulant & norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Insufflation: approx. 70% Oral: approx. 30% (range: 11–52%) |

| Protein binding | 10–33% |

| Metabolism | Liver (80%) mostly CES1A1-mediated |

| Elimination half-life | 2–3 hours[10] |

| Duration of action |

|

| Excretion | Urine (90%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C14H19NO2 |

| Molar mass | 233.311 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 74 °C (165 °F) [11] |

| Boiling point | 136 °C (277 °F) [11] |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Methylphenidate, sold under the brand names Ritalin (/ˈrɪtəlɪn/ RIT-ə-lin) and Concerta (/kənˈsɜːrtə/ kən-SUR-tə) among others, is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant used medically to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and, to a lesser extent, narcolepsy. It is a primary medication for ADHD (e.g. in the UK[12]); it may be taken by mouth or applied to the skin, and different formulations have varying durations of effect, commonly ranging from 2–4 hours.[2]

Common adverse reactions of methylphenidate include: euphoria, dilated pupils, tachycardia, palpitations, headache, insomnia, anxiety, hyperhidrosis, weight loss, decreased appetite, dry mouth, nausea, and abdominal pain.[6] Withdrawal symptoms may include: chills, depression, drowsiness, dysphoria, exhaustion, headache, irritability, lethargy, nightmares, restlessness, suicidal thoughts, and weakness.[2]

Methylphenidate is believed to work by blocking the reuptake of dopamine and norepinephrine by neurons.[13][14] It is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant of the phenethylamine and piperidine classes.

Etymology

The word methylphenidate is a portmanteau of the chemical name, Methyl-2-phenyl-2-(piperidin-2-yl) acetate.

Uses

Methylphenidate is most commonly used to treat ADHD and narcolepsy.[15]

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Methylphenidate is used for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.[16] The dosage may vary and is titrated to effect, with some guidelines recommending initial treatment with a low dose.[17] Immediate-release methylphenidate is used daily along with the longer-acting form to achieve full-day control of symptoms.[18][19] Methylphenidate is not approved for children under six years of age.[20][21]

In children over age 6 and adolescents, the short-term benefits and cost-effectiveness of methylphenidate are well established.[22][23] A number of reviews have established the safety and effectiveness for individuals with ADHD over several years.[24][25][26]

Approximately 70% of those who use methylphenidate see improvements in ADHD symptoms.[27] Children with ADHD who use stimulant medications generally have better relationships with peers and family members, perform better in school, are less distractible and impulsive, and have longer attention spans.[24] There is evidence to suggest that children diagnosed with ADHD who do not receive treatment will have an increased risk of substance use disorders as adults.[28][29]

The precise magnitude of improvement in ADHD symptoms and quality of life produced by methylphenidate treatment remains uncertain (As of March 2023).[30] Methylphenidate is not included in the World Health Organization Essential Medicines List, as findings by the World Health Organization indicate evidence of benefit versus harm to be unclear in the treatment of ADHD.[31] A 2021 systematic review did not find clear evidence for using IR methylphenidate (immediate-release) for adults.[32]

Since ADHD diagnosis has increased around the world, methylphenidate may be misused as a "study drug" by some populations, which may be harmful.[33] This also applies to people who may be experiencing a different issue and are misdiagnosed with ADHD.[33] People in this category can then experience negative side-effects of the drug, which worsen their condition.[33]

Narcolepsy

Narcolepsy, a chronic sleep disorder characterized by overwhelming daytime drowsiness and uncontrollable sleep, is treated primarily with stimulants. Methylphenidate is considered effective in increasing wakefulness, vigilance, and performance.[34] Methylphenidate improves measures of somnolence on standardized tests, such as the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT), but performance does not improve to levels comparable to healthy people.[35]

Other medical uses

Methylphenidate may also be prescribed for off-label use in treatment-resistant cases of bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder.[36] It can also improve depression in several groups, including stroke, cancer, and HIV-positive patients.[37] There is weak evidence in favor of methylphenidate's effectiveness for depression,[38] including providing additional benefit in combination with antidepressants.[39] In individuals with terminal cancer, methylphenidate can be used to counteract opioid-induced somnolence, to increase the analgesic effects of opioids, to treat depression, and to improve cognitive function.[40] A 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis found that all studies on geriatric depression reported positive results of methylphenidate use; the review recommended short-term use in combination with citalopram.[41] A 2018 review found low-quality evidence supporting its use to treat apathy as seen in Alzheimer's disease, in addition to slight benefits for cognition and cognitive performance.[42]

Enhancing performance

Methylphenidate's efficacy as an athletic performance enhancer, cognitive enhancer, aphrodisiac, and euphoriant is supported by research.[43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51] However, the manner in which methylphenidate is used for these purposes (high dosages, alternate routes of administration, during sleep deprivation, etc.) can result in severe unintended side effects.[52][53][51] A 2015 review found that therapeutic doses of amphetamine and methylphenidate result in modest improvements in cognition, including working memory, episodic memory, and inhibitory control, in normal healthy adults;[54][lower-alpha 1][55][lower-alpha 2] the cognition-enhancing effects of these drugs are known to occur through the indirect activation of both dopamine receptor D1 and adrenoceptor α2 in the prefrontal cortex.[54] Methylphenidate and other ADHD stimulants also improve task saliency and increase arousal.[56][57] Stimulants such as amphetamine and methylphenidate can improve performance on difficult and boring tasks,[56][lower-alpha 3][57][58] and are used by some students as a study and test-taking aid.[33][59] Based upon studies of self-reported illicit stimulant use, performance-enhancing use rather than use as a recreational drug, is the primary reason that students use stimulants.[60]

Excessive doses of methylphenidate, above the therapeutic range, can interfere with working memory and cognitive control.[56][57] Like amphetamine and bupropion, methylphenidate increases stamina and endurance in humans primarily through reuptake inhibition of dopamine in the central nervous system.[61] Similar to the loss of cognitive enhancement when using large amounts, large doses of methylphenidate can induce side effects that impair athletic performance, such as rhabdomyolysis and hyperthermia.[9] While literature suggests it might improve cognition, most authors agree that using the drug as a study aid when an ADHD diagnosis is not present does not actually improve GPA.[33] Moreover, it has been suggested that students who use the drug for studying may be self-medicating for potentially deeper underlying issues.[33]

Contraindications

Methylphenidate is contraindicated for individuals with agitation, tics, glaucoma, heart defects or a hypersensitivity to any ingredients contained in methylphenidate pharmaceuticals.[9]

Pregnant women are advised to only use the medication if the benefits outweigh the potential risks.[62] Not enough human studies have been conducted to conclusively demonstrate an effect of methylphenidate on fetal development.[63] In 2018, a review concluded that it has not been teratogenic in rats and rabbits, and that it "is not a major human teratogen".[64]

Adverse effects

The most common side effects associated with methylphenidate (in standard and extended-release formulations) are appetite loss, dry mouth, anxiety/nervousness, nausea, and insomnia.[66] Gastrointestinal adverse effects may include abdominal pain and weight loss. Nervous system adverse effects may include akathisia (agitation/restlessness), irritability, dyskinesia (tics), Oromandibular dystonia,[67] lethargy (drowsiness/fatigue), and dizziness. Cardiac adverse effects may include palpitations, changes in blood pressure, and heart rate (typically mild), and tachycardia (rapid heart rate).[68] Ophthalmologic adverse effects may include blurred vision caused by pupil dilatation and dry eyes, with less frequent reports of diplopia and mydriasis.[contradictory][69][70]

Smokers with ADHD who take methylphenidate may increase their nicotine dependence, and smoke more often than before they began using methylphenidate, with increased nicotine cravings and an average increase of 1.3 cigarettes per day.[71]

There is some evidence of mild reductions in height with prolonged treatment in children.[72] This has been estimated at 1 centimetre (0.4 in) or less per year during the first three years with a total decrease of 3 centimetres (1.2 in) over 10 years.[73][74]

Hypersensitivity (including skin rash, urticaria, and fever) is sometimes reported when using transdermal methylphenidate. The Daytrana patch has a much higher rate of skin reactions than oral methylphenidate.[75]

Methylphenidate can worsen psychosis in people who are psychotic, and in very rare cases it has been associated with the emergence of new psychotic symptoms.[76] It should be used with extreme caution in people with bipolar disorder due to the potential induction of mania or hypomania.[77] There have been very rare reports of suicidal ideation, but some authors claim that evidence does not support a link.[72] Logorrhea is occasionally reported and visual hallucinations are very rarely reported.[69] Priapism is a very rare adverse event that can be potentially serious.[78]

U.S. Food and Drug Administration-commissioned studies in 2011 indicate that in children, young adults, and adults, there is no association between serious adverse cardiovascular events (sudden death, heart attack, and stroke) and the medical use of methylphenidate or other ADHD stimulants.[79]

Because some adverse effects may only emerge during chronic use of methylphenidate, a constant watch for adverse effects is recommended.[80]

A 2018 Cochrane review found that methylphenidate might be associated with serious side effects such as heart problems, psychosis, and death. The certainty of the evidence was stated as very low.[81]

The same review found tentative evidence that it may cause both serious and non-serious adverse effects in children.[81][lower-alpha 4]

Overdose

The symptoms of a moderate acute overdose on methylphenidate primarily arise from central nervous system overstimulation; these symptoms include: vomiting, nausea, agitation, tremors, hyperreflexia, muscle twitching, euphoria, confusion, hallucinations, delirium, hyperthermia, sweating, flushing, headache, tachycardia, heart palpitations, cardiac arrhythmias, hypertension, mydriasis, and dryness of mucous membranes.[9][82] A severe overdose may involve symptoms such as hyperpyrexia, sympathomimetic toxidrome, convulsions, paranoia, stereotypy (a repetitive movement disorder), rhabdomyolysis, coma, and circulatory collapse.[9][82][83][lower-alpha 5] A methylphenidate overdose is rarely fatal with appropriate care.[83] Following injection of methylphenidate tablets into an artery, severe toxic reactions involving abscess formation and necrosis have been reported.[84]

Treatment of a methylphenidate overdose typically involves the administration of benzodiazepines, with antipsychotics, α-adrenoceptor agonists and propofol serving as second-line therapies.[83]

Addiction and dependence

Methylphenidate is a stimulant with an addiction liability and dependence liability similar to amphetamine. It has moderate liability among addictive drugs;[85][86] accordingly, addiction and psychological dependence are possible and likely when methylphenidate is used at high doses as a recreational drug.[86] When used above the medical dose range, stimulants are associated with the development of stimulant psychosis.[87]

Biomolecular mechanisms

Methylphenidate has the potential to induce euphoria due to its pharmacodynamic effect (i.e., dopamine reuptake inhibition) in the brain's reward system. At therapeutic doses, ADHD stimulants do not sufficiently activate the reward system; consequently, when taken as directed in doses that are commonly prescribed for the treatment of ADHD, methylphenidate use lacks the capacity to cause an addiction.[86]

Interactions

Methylphenidate may inhibit the metabolism of vitamin K anticoagulants, certain anticonvulsants, and some antidepressants (tricyclic antidepressants, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors). Concomitant administration may require dose adjustments, possibly assisted by monitoring of plasma drug concentrations.[8] There are several case reports of methylphenidate inducing serotonin syndrome with concomitant administration of antidepressants.[88][89][90][91]

When methylphenidate is coingested with ethanol, a metabolite called ethylphenidate is formed via hepatic transesterification,[92][93] not unlike the hepatic formation of cocaethylene from cocaine and ethanol. The reduced potency of ethylphenidate and its minor formation means it does not contribute to the pharmacological profile at therapeutic doses and even in overdose cases ethylphenidate concentrations remain negligible.[94][93]

Coingestion of alcohol (ethanol) also increases the blood plasma levels of d-methylphenidate by up to 40%.[95]

Liver toxicity from methylphenidate is extremely rare, but limited evidence suggests that intake of β-adrenergic agonists with methylphenidate may increase the risk of liver toxicity.[96]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Neurotransmitter transporter |

Measure (units) |

dl-MPH | d-MPH | l-MPH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAT | Ki (nM) | 121 | 161 | 2250 |

| IC50 (nM) | 20 | 23 | 1600 | |

| NET | Ki (nM) | 788 | 206 | >10000 |

| IC50 (nM) | 51 | 39 | 980 | |

| SERT | Ki (nM) | >10000 | >10000 | >6700 |

| IC50 (nM) | — | >10000 | >10000 | |

| GPCR | Measure (units) |

dl-MPH | d-MPH | l-MPH |

| 5-HT1A | Ki (nM) | 5000 | 3400 | >10000 |

| IC50 (nM) | 10000 | 6800 | >10000 | |

| 5-HT2B | Ki (nM) | >10000 | 4700 | >10000 |

| IC50 (nM) | >10000 | 4900 | >10000 |

Methylphenidate primarily acts as a norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI). It is a benzylpiperidine and phenethylamine derivative which also shares part of its basic structure with catecholamines.

Methylphenidate is a psychostimulant and increases the activity of the central nervous system through inhibition on reuptake of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine and dopamine. As models of ADHD suggest, it is associated with functional impairments in some of the brain's neurotransmitter systems, particularly those involving dopamine in the mesocortical and mesolimbic pathways and norepinephrine in the prefrontal cortex and locus coeruleus.[100] Psychostimulants like methylphenidate and amphetamine may be effective in treating ADHD because they increase neurotransmitter activity in these systems. When reuptake of those neurotransmitters is halted, its concentration and effects in the synapse increase and last longer, respectively. Therefore, methylphenidate is called a norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor.[94] By increasing the effects of norepinephrine and dopamine, methylphenidate increases the activity of the central nervous system and produces effects such as increased alertness, reduced fatigue, and improved attention.[100][101]

Methylphenidate is most active at modulating levels of dopamine (DA) and to a lesser extent norepinephrine (NE).[102] Methylphenidate binds to and blocks dopamine transporters (DAT) and norepinephrine transporters (NET).[103] Variability exists between DAT blockade, and extracellular dopamine, leading to the hypothesis that methylphenidate amplifies basal dopamine activity, leading to nonresponse in those with low basal DA activity.[104] On average, methylphenidate elicits a 3–4 times increase in dopamine and norepinephrine in the striatum and prefrontal cortex.[1] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies suggest that long-term treatment with ADHD stimulants (specifically, amphetamine and methylphenidate) decreases abnormalities in brain structure and function found in subjects with ADHD.[105][106][107][lower-alpha 6]

Both amphetamine and methylphenidate are predominantly dopaminergic drugs, yet their mechanisms of action are distinct. Methylphenidate acts as a norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor, while amphetamine is both a releasing agent and reuptake inhibitor of dopamine and norepinephrine. Methylphenidate's mechanism of action in the release of dopamine and norepinephrine is fundamentally different from most other phenethylamine derivatives, as methylphenidate is thought to increase neuronal firing rate,[108][109][110] whereas amphetamine reduces firing rate, but causes monoamine release by reversing the flow of the monoamines through monoamine transporters via a diverse set of mechanisms, including TAAR1 activation and modulation of VMAT2 function, among other mechanisms.[111][112][lower-alpha 7][113][lower-alpha 8] The difference in mechanism of action between methylphenidate and amphetamine results in methylphenidate inhibiting amphetamine's effects on monoamine transporters when they are co-administered.[111][better source needed]

Methylphenidate has both dopamine transporter and norepinephrine transporter binding affinity, with the dextromethylphenidate enantiomers displaying a prominent affinity for the norepinephrine transporter.[114] Both the dextrorotary and levorotary enantiomers displayed receptor affinity for the serotonergic 5HT1A and 5HT2B subtypes, though direct binding to the serotonin transporter was not observed.[99] A later study confirmed the d-threo-methylphenidate (dexmethylphenidate) binding to the 5HT1A receptor, but no significant activity on the 5HT2B receptor was found.[115]

There exist some paradoxical findings that oppose the notion that methylphenidate acts as silent antagonist of the DAT (DAT inhibitor).[116] 80% occupancy of the DAT is necessary for methylphenidate's euphoriant effect, but re-administration of methylphenidate beyond this level of DAT occupancy has been found to produce similarly potent euphoriant effects (despite DAT occupancy being unchanged with repeated administration).[116] By contrast, other DAT inhibitors such as bupropion have not been observed to exhibit this effect.[117] These observations have prompted the hypothesis that methylphenidate may act as a "DAT inverse agonist" or "negative allosteric modifier of the DAT" by reversing the direction of the dopamine efflux by the DAT at higher dosages.[118]

Methylphenidate may protect neurons from the neurotoxic effects of Parkinson's disease and methamphetamine use disorder.[119] The hypothesized mechanism of neuroprotection is through inhibition of methamphetamine–DAT interactions, and through reducing cytosolic dopamine, leading to decreased production of dopamine-related reactive oxygen species.[119]

The dextrorotary enantiomers are significantly more potent than the levorotary enantiomers, and some medications therefore only contain dexmethylphenidate.[102] The studied maximized daily dosage of OROS methylphenidate appears to be 144 mg/day.[120]

Pharmacokinetics

Methylphenidate taken by mouth has a bioavailability of 11–52% with a duration of action around 2–4 hours for instant-release (i.e. Ritalin), 3–8 hours for sustained-release (i.e. Ritalin SR), and 8–12 hours for extended-release (i.e. Concerta). The half-life of methylphenidate is 2–3 hours, depending on the individual. The peak plasma time is achieved at about 2 hours.[10] Methylphenidate has a low plasma protein binding of 10–33% and a volume of distribution of 2.65 L/kg.[7]

Dextromethylphenidate is much more bioavailable than levomethylphenidate when administered orally, and is primarily responsible for the psychoactivity of racemic methylphenidate.[10]

The oral bioavailability and speed of absorption for immediate-release methylphenidate is increased when administered with a meal.[121] The effects of a high fat meal on the observed Cmax differ between some extended-release formulations, with combined IR/ER and OROS formulations showing reduced Cmax levels[122] while liquid-based extended-release formulations showed increased Cmax levels when administered with a high-fat meal, according to some researchers.[123] A 2003 study, however, showed no difference between a high-fat meal administration and a fasting administration of oral methylphenidate.[124]

Methylphenidate is metabolized into ritalinic acid by CES1A1 enzymes in the liver. Dextromethylphenidate is selectively metabolized at a slower rate than levomethylphenidate.[125] 97% of the metabolised drug is excreted in the urine, and between 1 and 3% is excreted in the faeces. A small amount, less than 1%, of the drug is excreted in the urine in its unchanged form.[7]

Chemistry

- Despite the claim made by some urban legends, it is not a cocaine derivative nor analog; cocaine is a local anesthetic and ligand channel blocker with SNDRI action, while methylphenidate is an NDRI with 2–3 fold selectivity for the dopamine transporter (DAT) over the norepinephrine transporter (NET). Cocaine is also more potent in serotonin transporters (SERTs) than NDRI sites.[126][127]

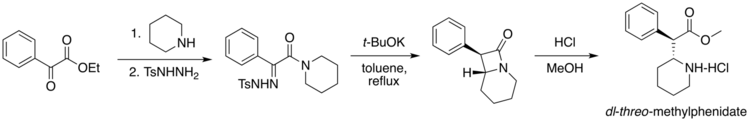

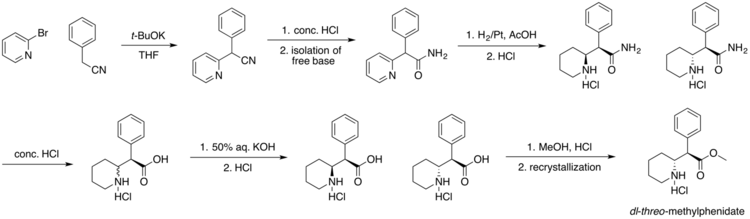

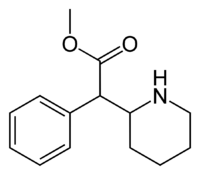

Four isomers of methylphenidate are possible, since the molecule has two chiral centers. One pair of threo isomers and one pair of erythro are distinguished, from which primarily d-threo-methylphenidate exhibits the pharmacologically desired effects.[102][128] The erythro diastereomers are pressor amines, a property not shared with the threo diastereomers. When the drug was first introduced it was sold as a 4:1 mixture of erythro:threo diastereomers, but it was later reformulated to contain only the threo diastereomers. "TMP" refers to a threo product that does not contain any erythro diastereomers, i.e. (±)-threo-methylphenidate. Since the threo isomers are energetically favored, it is easy to epimerize out any of the undesired erythro isomers. The drug that contains only dextrorotatory methylphenidate is sometimes called d-TMP, although this name is only rarely used and it is much more commonly referred to as dexmethylphenidate, d-MPH, or d-threo-methylphenidate. A review on the synthesis of enantiomerically pure (2R,2'R)-(+)-threo-methylphenidate hydrochloride has been published.[129]

Detection in biological fluids

The concentration of methylphenidate or ritalinic acid, its major metabolite, may be quantified in plasma, serum or whole blood in order to monitor compliance in those receiving the drug therapeutically, to confirm the diagnosis in potential poisoning victims or to assist in the forensic investigation in a case of fatal overdosage.[132]

History

Methylphenidate was first synthesized in 1944 and was approved for medical use in the United States in 1955.[133][134][135] It was synthesized by chemist Leandro Panizzon and sold by Swiss company CIBA (now Novartis).[133] He named the drug after his wife Margarita, nicknamed Rita, who used Ritalin to compensate for low blood pressure.[136] Methylphenidate was not reported to be a stimulant until 1954.[137][138] The drug was introduced for medical use in the United States in 1957.[139] Originally, it was marketed as a mixture of two racemates, 80% (±)-erythro and 20% (±)-threo, under the brand name Centedrin.[137] Subsequent studies of the racemates showed that the central stimulant activity is associated with the threo racemate and were focused on the separation and interconversion of the erythro isomer into the more active threo isomer.[137][140][141][142] The erythro isomer was eliminated, and now modern formulations of methyphenidate contain only the threo isomer in a 50:50 mixture of d- and l-isomers.[137]

Methylphenidate was first used to allay barbiturate-induced coma, narcolepsy and depression.[143] It was later used to treat memory deficits in the elderly.[144] Beginning in the 1960s, it was used to treat children with ADHD based on earlier work, starting with the studies by American psychiatrist Charles Bradley[145] on the use of psychostimulant drugs, such as Benzedrine, with then called "maladjusted children".[146] Production and prescription of methylphenidate rose significantly in the 1990s, especially in the United States, as the ADHD diagnosis came to be better understood and more generally accepted within the medical and mental health communities.[147]

In 2000, Alza Corporation received US FDA approval to market Concerta, an extended-release form of methylphenidate.[8][148][149]

It was estimated that the number of doses of methylphenidate used globally in 2013 increased by 66% compared to 2012.[150] In 2021, it was the 43rd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 15 million prescriptions.[151][152] It is available as a generic medication.[2]

Society and culture

Names

Methylphenidate is sold in the majority of countries worldwide.[153]:8–9 Brand names for methylphenidate include Ritalin (in honor of Rita, the wife of the molecule discoverer), Rilatine (in Belgium to avoid a conflict of commercial name with the RIT pharmaceutical company), Concerta,[8] Medikinet, Adaphen, Addwize, Inspiral, Methmild, Artige, Attenta, Cognil, Konsenidat, Equasym, Foquest,[154] Methylin, Penid, Phenida, Prohiper, and Tradea.[153]:8–9

Available forms

The dextrorotary enantiomer of methylphenidate, known as dexmethylphenidate, is sold as a generic and under the brand names Focalin and Attenade in both an immediate-release and an extended-release form. There is some evidence that dexmethylphenidate has better bioavailability and a longer duration of action than methylphenidate.[155]

Immediate-release

Structural formula for the substance among Ritalin tablet series. (Ritalin, Ritalin LA, Ritalin SR.) The volume of distribution was 2.65±1.11 L/kg for d-methylphenidate and 1.80±0.91 L/kg for l-methylphenidate subsequent to swallow of Ritalin tablet.[6]

Structural formula for the substance inside Concerta tablet. Following administration of Concerta, plasma concentrations of the l-isomer were approximately 1/40 the plasma concentrations of the d-isomer.[8] Note that the substance is the same as for Concerta - the differences lies in other aspects of the individual pills.

Methylphenidate was originally available as an immediate-release racemic mixture formulation under the Novartis brand name Ritalin, although a variety of generics are available, some under other brand names. Generic brand names include Ritalina, Rilatine, Attenta, Medikinet, Metadate, Methylin, Penid, Tranquilyn, and Rubifen.[citation needed]

Extended-release

Extended-release methylphenidate products include:

| Brand name(s) | Generic name(s)[156]Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; refs with no name must have content[157][158]

|

Duration | Dosage form |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aptensio XR (US); Biphentin (CA) |

Currently unavailable | 12 hours[159][160] | XR capsule |

| Concerta (US/CA/AU); Concerta XL (UK) |

methylphenidate ER (US/CA);[lower-roman 1] methylphenidate ER‑C (CA)[lower-roman 2] |

12 hours[161] | OROS tablet |

| Quillivant XR (US) | Currently unavailable | 12 hours[161] | oral suspension |

| Daytrana (US) | methylphenidate film, extended release;transdermal (US)[lower-roman 3] | 11 hours[162] | transdermal patch |

| Metadate CD (US); Equasym XL (UK) |

methylphenidate ER (US)[lower-roman 4] | 8–10 hours[161] | CD/XL capsule |

| QuilliChew ER (US) | Currently unavailable | 8 hours[163] | chewable tablet |

| Ritalin LA (US/AU); Medikinet XL (UK) |

methylphenidate ER (US)[lower-roman 5] | 8 hours[161] | ER capsule |

| Ritalin SR (US/CA/UK); Rubifen SR (NZ) |

Metadate ER (US);[lower-roman 6] Methylin ER (US);[lower-roman 7] methylphenidate SR (US/CA)[lower-roman 8] |

5–8 hours[161] | CR tablet |

| |||

Concerta tablets are marked with the letters "ALZA" and followed by: "18", "27", "36", or "54", relating to the dosage strength in milligrams. Approximately 22% of the dose is immediate-release,[164] and the remaining 78% of the dose is released over 10–12 hours post-ingestion, with an initial increase over the first 6–7 hours, and subsequent decline in the released drug.[165]

Ritalin LA capsules are marked with the letters "NVR" (abbrev.: Novartis) and followed by: "R20", "R30", or "R40", depending on the (mg) dosage strength. Ritalin LA[68] provides two standard doses – half the total dose being released immediately and the other half released four hours later. In total, each capsule is effective for about eight hours.

Metadate CD capsules contain two types of beads: 30% are immediate-release, and the other 70% are evenly sustained release.[166]

Medikinet Retard/CR/Adult/Modified Release tablets are an extended-release oral capsule form of methylphenidate. It delivers 50% of the dosage as IR MPH and the remaining 50% in 3–4 hours.[167][168]

Skin patch

A methylphenidate skin patch is sold under the brand name Daytrana in the United States. It was developed and marketed by Noven Pharmaceuticals and approved in the US in 2006.[9] It is also referred to as methylphenidate transdermal system (MTS). It is approved as a once-daily treatment in children with ADHD aged 6–17 years. It is mainly prescribed as a second-line treatment when oral forms are not well tolerated, or if people have difficulty with compliance. Noven's original FDA submission indicated that it should be used for 12 hours. When the FDA rejected the submission, they requested evidence that a shorter time period was safe and effective; Noven provided such evidence, and it was approved for a 9-hour period.[169]

Orally administered methylphenidate is subject to first-pass metabolism, by which the levo-isomer is extensively metabolized. By circumventing this first-pass metabolism, the relative concentrations of ℓ-threo-methylphenidate are much higher with transdermal administration (50–60% of those of dexmethylphenidate instead of about 14–27%).[170]

A 39 nanograms/mL peak serum concentration of methylphenidate has been found to occur between 7.5–10.5 hours after administration.[9] However, the onset to peak effect is 2 hours, and the clinical effects remain up to 2 hours after the patch has been removed. The absorption is increased when the transdermal patch is applied onto inflamed skin or skin that has been exposed to heat. The absorption lasts for approximately 9 hours after application (onto normal, unexposed to heat and uninflamed skin). 90% of the medication is excreted in the urine as metabolites and unchanged drug.[9]

Parenteral formulation

When it was released in the United States, methylphenidate was available from CIBA in a parenteral form for use by medical professionals. It came in 10mL multiple-dose vials containing 100 mg methylphenidate HCl and 100 mg lactose in lyophilized (freeze-dried) form. It was also available as single-dose ampoules containing 20 mg methylphenidate HCl. Instructions were to reconstitute with 10mL sterile solvent (water). The indication was 10 to 20 mg (1.0mL from MDV's, up to one full single-use ampoule) to produce a focused, talkative state that could help certain patients breakdown the resistance to therapy. Parenteral methylphenidate was discontinued out of a concern for the actual benefit and of inducing a psychic dependence. This is not truth serum in the normal sense, as it does not impair the ability to control the flow of information like a barbiturate agent (Pentothal©) or similar might.[citation needed]

Cost

Brand-name and generic formulations are available.[2]

Legal status

Internationally, methylphenidate is a Schedule II drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[171]

Legal

|

Controlled Substance

|

Illegal

|

| Country/Territory | Status | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| "Schedule 8" controlled substance. Such drugs must be kept in a lockable safe until dispensed and possession without prescription is punishable by fines and imprisonment. | [172] | ||

| Schedule III of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act and is illegal to possess without a prescription, with unlawful possession punishable by up to three years imprisonment, or (via summary conviction) by up to one year imprisonment and/or fines of up to two thousand dollars. Unlawful possession for the purpose of trafficking is punishable by up to ten years imprisonment, or (via summary conviction) by up to eighteen months imprisonment. | [173] | ||

| Schedule 1 Illicit Drug under the Illicit Drugs Control Act 2004 | [174] | ||

| Covered by the "narcotics" schedule, prescription and distribution conditions are restricted, with hospital or city specialist-only (pediatrician for children, psychiatrist or neurologist for adults) prescription for the initial treatment and yearly consultations.[175] | |||

| Controlled under the schedule 1 of the Dangerous Drugs Ordinance (cap. 134). | [176] | ||

| Methylphenidate is a schedule X drug and is controlled by the Drugs and Cosmetics Rule, 1945. It is dispensed only by physician's prescription. Legally, 2 grams of methylphenidate is classified as a small quantity, and 50 grams as a large or commercial quantity. | [177][178] | ||

| In New Zealand, methylphenidate is a 'class B2 controlled substance'. Unlawful possession is punishable by six-month prison sentence and distribution by a 14-year sentence. | |||

| List I controlled psychotropic substance without recognized medical value. The Constant Committee for Drug Control of the Russian Ministry of Health has put methylphenidate and its derivatives on the National List of Narcotics, Psychotropic Substances and Their Precursors, and the Government banned methylphenidate for any use on 25 October 2014. | [179] | ||

| List II controlled substance with recognized medical value. Possession without a prescription is punishable by up to three years in prison. | [180] | ||

| Controlled 'Class B' substance. Possession without prescription carries a sentence up to 5 years or an unlimited fine, or both; supplying methylphenidate is 14 years or an unlimited fine, or both. | [181] | ||

| Classified as a Schedule II controlled substance, the designation used for substances that have a recognized medical value but present a high potential for misuse. | [182] |

Controversy

Methylphenidate has been the subject of controversy in relation to its use in the treatment of ADHD. The prescription of psychostimulant medication to children to reduce ADHD symptoms has been a major point of criticism.[183][need quotation to verify] The contention that methylphenidate acts as a gateway drug has been discredited by multiple sources,[184] according to which abuse is statistically very low and "stimulant therapy in childhood does not increase the risk for subsequent drug and alcohol abuse disorders later in life".[185] A study found that ADHD medication was not associated with an increased risk of cigarette use, and in fact, stimulant treatments such as Ritalin seemed to lower this risk.[186] People treated with stimulants such as methylphenidate during childhood were less likely to have substance use disorders in adulthood.[187]

Among countries with the highest rates of use of methylphenidate medication is Iceland,[188] where research shows that the drug was the most commonly used substance among people who inject drugs.[189] The study involved 108 people who inject drugs and 88% of them had injected methylphenidate within the last 30 days and for 63% of them, methylphenidate was the most preferred substance.

Treatment of ADHD by way of methylphenidate has led to legal actions, including malpractice suits regarding informed consent, inadequate information on side effects, misdiagnosis, and coercive use of medications by school systems.[190]

Research

Methylphenidate may be effective as a treatment for apathy in Alzheimer's disease.[191]

Replacement therapy

Methylphenidate has shown some benefits as a replacement therapy for individuals who are addicted to and dependent upon methamphetamine.[192] Methylphenidate and amphetamine have been investigated as a chemical replacement for the treatment of cocaine addiction.[193][194] Its effectiveness in treatment of cocaine, psychostimulant addiction or psychological dependence has not been proven.[195]

Footnotes

- ↑ The procognitive actions of psychostimulants are only associated with low doses ... cognition-enhancing effects of psychostimulants involve the preferential elevation of catecholamines in the PFC and the subsequent activation of norepinephrine α2 and dopamine D1 receptors. ... This differential modulation of PFC-dependent processes across dose appears to be associated with the differential involvement of noradrenergic α2 versus α1 receptors.[54]

- ↑ The results of this meta-analysis ... do confirm the reality of cognitive enhancing effects for normal healthy adults in general, while also indicating that these effects are modest in size.[55]

- ↑ Therapeutic (relatively low) doses of psychostimulants, such as methylphenidate and amphetamine, improve performance on working memory tasks both in normal subjects and those with ADHD ... [It] is now believed that dopamine and norepinephrine, but not serotonin, produce the beneficial effects of stimulants on working memory. At abused (relatively high) doses, stimulants can interfere with working memory and cognitive control ... stimulants act not only on working memory function, but also on general levels of arousal and, within the nucleus accumbens, improve the saliency of tasks. Thus, stimulants improve performance on effortful but tedious tasks ... through indirect stimulation of dopamine and norepinephrine receptors.[56]

- ↑ "Our findings suggest that methylphenidate may be associated with a number of serious adverse events as well as a large number of non-serious adverse events in children" "Concerning adverse events associated with the treatment, our systematic review of randomised clinical trials (RCTs) demonstrated no increase in serious adverse events, but a high proportion of participants suffered a range of non-serious adverse events."[81]

- ↑ The management of amphetamine, dextroamphetamine, and methylphenidate overdose is largely supportive, with a focus on interruption of the sympathomimetic syndrome with judicious use of benzodiazepines. In cases where agitation, delirium, and movement disorders are unresponsive to benzodiazepines, second-line therapies include antipsychotics such as ziprasidone or haloperidol, central alpha-adrenoreceptor agonists such as dexmedetomidine, or propofol. ... However, fatalities are rare with appropriate care.[83]

- ↑ Basal ganglia regions like the right globus pallidus, the right putamen, and the nucleus caudatus are structurally affected in children with ADHD. These changes and alterations in limbic regions like ACC and amygdala are more pronounced in non-treated populations and seem to diminish over time from child to adulthood. Treatment seems to have positive effects on brain structure.[107]

- ↑ VMAT2 is the CNS vesicular transporter for not only the biogenic amines DA, NE, EPI, 5-HT, and HIS, but likely also for the trace amines TYR, PEA, and thyronamine (THYR) ... AMPH release of DA from synapses requires both an action at VMAT2 to release DA to the cytoplasm and a concerted release of DA from the cytoplasm via "reverse transport" through DAT.[112]

- ↑ Despite the challenges in determining synaptic vesicle pH, the proton gradient across the vesicle membrane is of fundamental importance for its function. Exposure of isolated catecholamine vesicles to protonophores collapses the pH gradient and rapidly redistributes transmitter from inside to outside the vesicle. ... Amphetamine and its derivatives like methamphetamine are weak base compounds that are the only widely used class of drugs known to elicit transmitter release by a non-exocytic mechanism. As substrates for both DAT and VMAT, amphetamines can be taken up to the cytosol and then sequestered in vesicles, where they act to collapse the vesicular pH gradient.[113]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Amfetamine and methylphenidate medications for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: complementary treatment options". European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 21 (9): 477–492. September 2012. doi:10.1007/s00787-012-0286-5. PMID 22763750.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 "Methylphenidate Hydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". AHFS. https://www.drugs.com/monograph/methylphenidate-hydrochloride.html.

- ↑ Today's Medical Assistant: Clinical and administrative procedures. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2012. p. 571. ISBN 9781455701506. https://books.google.com/books?id=YalYPI1KqTQC&pg=PA571. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ↑ "Ritalin Product information". 25 April 2012. https://health-products.canada.ca/dpd-bdpp/info.do?lang=en&code=800.

- ↑ "Controlled Drugs and Substances Act". 31 March 2022. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-38.8/FullText.html.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Ritalin- methylphenidate hydrochloride tablet". 26 June 2021. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=c0bf0835-6a2f-4067-a158-8b86c4b0668a.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Ritalin LA- methylphenidate hydrochloride capsule, extended release". 26 June 2021. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=effd952d-ac94-47bb-b107-589a4934dcca.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 "Concerta- methylphenidate hydrochloride tablet, extended release". 1 July 2021. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=1a88218c-5b18-4220-8f56-526de1a276cd.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 "Daytrana- methylphenidate patch". 15 June 2021. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=2c312c31-3198-4775-91ab-294e0b4b9e7f.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Pharmacokinetics and clinical effectiveness of methylphenidate". Clinical Pharmacokinetics 37 (6): 457–470. December 1999. doi:10.2165/00003088-199937060-00002. PMID 10628897.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Methylphenidate". https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/4158.

- ↑ "Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Treatment". 24 December 2021. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd/treatment/.

- ↑ "Neurobiology of executive functions: catecholamine influences on prefrontal cortical functions". Biological Psychiatry 57 (11): 1377–1384. June 2005. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.08.019. PMID 15950011.

- ↑ Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific basis and practical applications (4th ed.). Cambridge University Press. 11 April 2013. ISBN 978-1107686465.

- ↑ "Methylphenidate". https://www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB00422.

- ↑ "Stimulants: use and abuse in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Current Opinion in Pharmacology 5 (1): 87–93. February 2005. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2004.10.001. PMID 15661631.

- ↑ "Methylphenidate dose optimization for ADHD treatment: review of safety, efficacy, and clinical necessity". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 13: 1741–1751. 2 June 2021. doi:10.2147/NDT.S130444. PMID 28740389.

- ↑ "ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit / hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents". Pediatrics 128 (5): 1007–1022. November 2011. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2654. PMID 22003063.

- ↑ Handbook of Adolescent Health Care. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health / Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2009. ISBN 978-0-7817-9020-8. OCLC 226304727.:722

- ↑ "Psychopharmacology for young children: clinical needs and research opportunities". Pediatrics 108 (4): 983–989. October 2001. doi:10.1542/peds.108.4.983. PMID 11581454.

- ↑ "Integrative neuroscience approach to predict ADHD stimulant response". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics 6 (5): 753–763. May 2006. doi:10.1586/14737175.6.5.753. PMID 16734523.

- ↑ "Methylphenidate in children with hyperactivity: review and cost-utility analysis". Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 10 (2): 85–94. 2001. doi:10.1002/pds.564. PMID 11499858.

- ↑ "Clinical inquiries. Is methylphenidate useful for treating adolescents with ADHD?". The Journal of Family Practice 53 (8): 659–661. August 2004. PMID 15298843. http://www.jfponline.com/Pages.asp?AID=1753. Retrieved 30 April 2009.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "Chapter 3: Medications for ADHD". Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook: A physician's guide to ADHD (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer. 2010. pp. 111–113. ISBN 9781441913968.

- ↑ "Long-term outcomes with medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: current status of knowledge". CNS Drugs 25 (7): 539–554. July 2011. doi:10.2165/11589380-000000000-00000. PMID 21699268.

- ↑ "Chapter 3: Medications for ADHD". Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook: A physician's guide to ADHD (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer. 2010. pp. 121–123. ISBN 9781441913968.

- ↑ "Practice parameter for the use of stimulant medications in the treatment of children, adolescents, and adults". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 41 (2 Suppl): 26S–49S. February 2002. doi:10.1097/00004583-200202001-00003. PMID 11833633.

- ↑ "Effect of stimulant medications for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on later substance use and the potential for stimulant misuse, abuse, and diversion". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 68 (11): 15–22. 2007. doi:10.4088/jcp.1107e28. PMID 18307377.

- ↑ "Does stimulant therapy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder beget later substance abuse? A meta-analytic review of the literature". Pediatrics 111 (1): 179–185. January 2003. doi:10.1542/peds.111.1.179. PMID 12509574.

- ↑ "Methylphenidate for children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2023 (3): CD009885. 27 March 2023. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009885.pub3. PMID 36971690. PMC 10042435. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369558291. "the certainty of the evidence for all outcomes is very low and therefore the true magnitude of effects remain unclear".

- ↑ "eEML - Electronic Essential Medicines List". https://list.essentialmeds.org/recommendations/1200.

- ↑ "Immediate-release methylphenidate for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Wiley) 1 (1): CD013011. January 2021. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd013011.pub2. PMID 33460048.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 "Mitigating risks of students use of study drugs through understanding motivations for use and applying harm reduction theory: a literature review". Harm Reduction Journal 14 (1): 68. October 2017. doi:10.1186/s12954-017-0194-6. PMID 28985738.

- ↑ "Treatment modalities for narcolepsy". Neurology 50 (2 Suppl 1): S43–S48. February 1998. doi:10.1212/WNL.50.2_Suppl_1.S43. PMID 9484423.

- ↑ "Evaluation of treatment with stimulants in narcolepsy". Sleep 17 (8 Suppl): S103–S106. December 1994. doi:10.1093/sleep/17.suppl_8.S103. PMID 7701190.

- ↑ "Wake-promoting pharmacotherapy for psychiatric disorders". Current Psychiatry Reports 16 (12): 524. December 2014. doi:10.1007/s11920-014-0524-2. PMID 25312027.

- ↑ "Methylphenidate: A review of its neuropharmacological, neuropsychological, and adverse clinical effects". Human Psychopharmacology 19 (3): 151–180. April 2004. doi:10.1002/hup.579. PMID 15079851.

- ↑ "Comparative efficacy and safety of stimulant-type medications for depression: A systematic review and network meta-analysis". Journal of Affective Disorders 292: 416–423. September 2021. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.119. PMID 34144366.

- ↑ "A Review of Psychostimulants for Adults With Depression". Federal Practitioner 32 (Suppl 3): 30S–37S. April 2015. PMID 30766117.

- ↑ "Palliative uses of methylphenidate in patients with cancer: a review". Journal of Clinical Oncology 20 (1): 335–339. January 2002. doi:10.1200/JCO.20.1.335. PMID 11773187.

- ↑ "Methylphenidate use in geriatric depression: A systematic review". International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 36 (9): 1304–1312. September 2021. doi:10.1002/gps.5536. PMID 33829530.

- ↑ "Pharmacological interventions for apathy in Alzheimer's disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 5 (6): CD012197. May 2018. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012197.pub2. PMID 29727467.

- ↑ "Treatment" (in en). 1 June 2018. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd/treatment/.

- ↑ "Chronic oral methylphenidate treatment reversibly increases striatal dopamine transporter and dopamine type 1 receptor binding in rats". Journal of Neural Transmission 124 (5): 655–667. May 2017. doi:10.1007/s00702-017-1680-4. PMID 28116523.

- ↑ "The cognition-enhancing effects of psychostimulants involve direct action in the prefrontal cortex". Biological Psychiatry 77 (11): 940–950. June 2015. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.09.013. PMID 25499957.

- ↑ "Prescription Stimulants' Effects on Healthy Inhibitory Control, Working Memory, and Episodic Memory: A Meta-analysis". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 27 (6): 1069–1089. June 2015. doi:10.1162/jocn_a_00776. PMID 25591060. https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1141&context=neuroethics_pubs. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ↑ "From Clinical Application to Cognitive Enhancement: The Example of Methylphenidate". Current Neuropharmacology 14 (1): 17–27. 2016. doi:10.2174/1570159x13666150407225902. PMID 26813119.

- ↑ "Use of cognitive enhancers: methylphenidate and analogs". European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 23 (1): 3–15. January 2019. doi:10.26355/eurrev_201901_16741. PMID 30657540.

- ↑ "Cognitive enhancement effects of stimulants: a randomized controlled trial testing methylphenidate, modafinil, and caffeine". Psychopharmacology 238 (2): 441–451. February 2021. doi:10.1007/s00213-020-05691-w. PMID 33201262.

- ↑ "Sexual desire disorders". Psychiatry 5 (6): 50–55. June 2008. PMID 19727285.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 "ADHD Prescription Medications and Their Effect on Athletic Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Sports Medicine - Open 8 (1): 5. January 2022. doi:10.1186/s40798-021-00374-y. PMID 35022919.

- ↑ "Heat-related illness risk with methylphenidate use" (in English). Journal of Pediatric Health Care 25 (2): 127–132. 1 March 2011. doi:10.1016/j.pedhc.2010.07.006. PMID 21320685.

- ↑ "Cardiovascular and temperature adverse actions of stimulants". British Journal of Pharmacology 178 (13): 2551–2568. July 2021. doi:10.1111/bph.15465. PMID 33786822.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 "The cognition-enhancing effects of psychostimulants involve direct action in the prefrontal cortex". Biological Psychiatry 77 (11): 940–950. June 2015. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.09.013. PMID 25499957.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 "Prescription Stimulants' Effects on Healthy Inhibitory Control, Working Memory, and Episodic Memory: A Meta-analysis". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 27 (6): 1069–1089. June 2015. doi:10.1162/jocn_a_00776. PMID 25591060. https://repository.upenn.edu/neuroethics_pubs/130. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 "Chapter 13: Higher cognitive function and behavioral control". Molecular Neuropharmacology: A foundation for clinical neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2009. p. 318. ISBN 9780071481274.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 "Psychostimulants and cognition: a continuum of behavioral and cognitive activation". Pharmacological Reviews 66 (1): 193–221. January 2014. doi:10.1124/pr.112.007054. PMID 24344115.

- ↑ "Non-specific effects of methylphenidate (Ritalin) on cognitive ability and decision-making of ADHD and healthy adults". Psychopharmacology 210 (4): 511–519. July 2010. doi:10.1007/s00213-010-1853-4. PMID 20424828.

- ↑ "Pills become an addictive study aid". JS Online. 26 March 2006. http://www.jsonline.com/story/index.aspx?id=410902.

- ↑ "Illicit use of specific prescription stimulants among college students: prevalence, motives, and routes of administration". Pharmacotherapy 26 (10): 1501–1510. October 2006. doi:10.1592/phco.26.10.1501. PMID 16999660.

- ↑ "Neurophysiological determinants of theoretical concepts and mechanisms involved in pacing". Sports Medicine 43 (5): 301–311. May 2013. doi:10.1007/s40279-013-0030-4. PMID 23456493.

- ↑ "Methylphenidate: Use During Pregnancy and Breastfeeding". Drugs.com. https://www.drugs.com/pregnancy/methylphenidate.html.

- ↑ "Exposure to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder medications during pregnancy". Canadian Family Physician 53 (7): 1153–1155. July 2007. PMID 17872810.

- ↑ "Pharmacological Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder During Pregnancy and Lactation". Pharmaceutical Research 35 (3): 46. February 2018. doi:10.1007/s11095-017-2323-z. PMID 29411149.

- ↑ "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". Lancet 369 (9566): 1047–1053. March 2007. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831.

- ↑ "Long-acting methylphenidate formulations in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review of head-to-head studies". BMC Psychiatry (Springer Science and Business Media LLC) 13 (1): 237. September 2013. doi:10.1186/1471-244x-13-237. PMID 24074240.

- ↑ "Oromandibular dystonia secondary to methylphenidate: A case report and literature review". Int Arch Health Sci 7: 108–111. 2020. doi:10.4103/iahs.iahs_71_19. https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA626978803&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&issn=23832568&p=AONE&sw=w&userGroupName=anon%7E859e3a3c. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 "Ritalin LA (methylphenidate hydrochloride) extended-release capsules". Novartis. http://www.pharma.us.novartis.com/product/pi/pdf/ritalin_la.pdf.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 "Drug therapy of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: current trends". Mens Sana Monographs 10 (1): 45–69. January 2012. doi:10.4103/0973-1229.87261. PMID 22654382.

- ↑ "Ocular side effects of selected systemic drugs". Optometry Clinics 2 (4): 73–96. 1992. PMID 1363080.

- ↑ "Long-term relationship between methylphenidate and tobacco consumption and nicotine craving in adults with ADHD in a prospective cohort study". European Neuropsychopharmacology 23 (6): 542–554. June 2013. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.06.004. PMID 22809706.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 "Practitioner review: current best practice in the management of adverse events during treatment with ADHD medications in children and adolescents". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 54 (3): 227–246. March 2013. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12036. PMID 23294014.

- ↑ "Growth on stimulant medication; clarifying the confusion: a review". Archives of Disease in Childhood 90 (8): 801–806. August 2005. doi:10.1136/adc.2004.056952. PMID 16040876.

- ↑ "ADHD, Multimodal Treatment, and Longitudinal outcome: Evidence, paradox, and challenge". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Cognitive Science 6 (1): 39–52. January 2015. doi:10.1002/wcs.1324. PMID 25558298.

- ↑ "Transdermal therapy for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder with the methylphenidate patch (MTS)". CNS Drugs 28 (3): 217–228. March 2014. doi:10.1007/s40263-014-0141-y. PMID 24532028.

- ↑ "Methylphenidate-induced psychosis in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: report of 3 new cases and review of the literature". Clinical Neuropharmacology 33 (4): 204–206. July 2010. doi:10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181e29174. PMID 20571380.

- ↑ "Frequency of stimulant treatment and of stimulant-associated mania / hypomania in bipolar disorder patients". Psychopharmacology Bulletin 41 (4): 37–47. 2008. PMID 19015628.

- ↑ "Methylphenidate ADHD medications: Drug safety communication – risk of long-lasting erections". 17 December 2013. https://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm378876.htm.

- ↑ "FDA drug safety communication: Safety review update of medications used to treat attention-ceficit / hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and young adults". 20 December 2011. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm277770.htm. "ADHD drugs and serious cardiovascular events in children and young adults". The New England Journal of Medicine 365 (20): 1896–1904. November 2011. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110212. PMID 22043968. "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Safety Review Update of Medications used to treat Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in adults". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 15 December 2011. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm279858.htm. "ADHD medications and risk of serious cardiovascular events in young and middle-aged adults". JAMA 306 (24): 2673–2683. December 2011. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1830. PMID 22161946.

- ↑ "Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Possible causes and treatment". International Journal of Clinical Practice 53 (7): 524–528. 1999. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.1999.tb11794.x. PMID 10692738.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 81.2 "Methylphenidate for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents - assessment of adverse events in non-randomised studies". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 5 (5): CD012069. May 2018. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012069.pub2. PMID 29744873.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 "Methylphenidate hydrochloride (PIM 344)". International Programme on Chemical Safety. http://www.inchem.org/documents/pims/pharm/pim344.htm.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 83.2 83.3 "Overdose of drugs for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: Clinical presentation, mechanisms of toxicity, and management". CNS Drugs 27 (7): 531–543. July 2013. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0084-8. PMID 23757186.

- ↑ "Severe toxicity due to injected but not oral or nasal abuse of methylphenidate tablets". Swiss Medical Weekly 141: w13267. 2011. doi:10.4414/smw.2011.13267. PMID 21984207.

- ↑ "Methylphenidate Abuse and Psychiatric Side Effects". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2 (5): 159–164. October 2000. doi:10.4088/PCC.v02n0502. PMID 15014637.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 86.2 "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and addictive disorders". Molecular Neuropharmacology: A foundation for clinical neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2009. p. 368. ISBN 9780071481274.

- ↑ "Risks of high-dose stimulants in the treatment of disorders of excessive somnolence: A case-control study". Sleep 28 (6): 667–672. June 2005. doi:10.1093/sleep/28.6.667. PMID 16477952.

- ↑ "Serotonin syndrome induced by augmentation of SSRI with methylphenidate". Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 62 (2): 246. April 2008. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01767.x. PMID 18412855.

- ↑ "Serotonin syndrome with sertraline and methylphenidate in an adolescent". Clinical Neuropharmacology 38 (2): 65–66. 2015. doi:10.1097/WNF.0000000000000075. PMID 25768857.

- ↑ "Manic switch and serotonin syndrome induced by augmentation of paroxetine with methylphenidate in a patient with major depression". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry 34 (4): 719–720. May 2010. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.03.016. PMID 20298736.

- ↑ "Serotonin syndrome". Neurology 45 (2): 219–223. February 1995. doi:10.1212/wnl.45.2.219. PMID 7854515.

- ↑ "New methylphenidate formulations for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery 2 (1): 121–143. January 2005. doi:10.1517/17425247.2.1.121. PMID 16296740.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 "Ethylphenidate formation in human subjects after the administration of a single dose of methylphenidate and ethanol". Drug Metabolism and Disposition 28 (6): 620–624. June 2000. PMID 10820132.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 "Detection of the novel metabolite ethylphenidate after methylphenidate overdose with alcohol coingestion". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 19 (4): 362–366. August 1999. doi:10.1097/00004714-199908000-00013. PMID 10440465.

- ↑ "Influence of ethanol and gender on methylphenidate pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 81 (3): 346–353. March 2007. doi:10.1038/sj.clpt.6100082. PMID 17339864.

- ↑ "Adrenergic modulation of hepatotoxicity". Drug Metabolism Reviews 29 (1–2): 329–353. 1997. doi:10.3109/03602539709037587. PMID 9187524.

- ↑ "Differential pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of methylphenidate enantiomers: Does chirality matter?". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 28 (3 Suppl 2): S54–S61. June 2008. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181733560. PMID 18480678.

- ↑ "Methylphenidate and its ethanol transesterification metabolite ethylphenidate: brain disposition, monoamine transporters and motor activity". Behavioural Pharmacology 18 (1): 39–51. February 2007. doi:10.1097/fbp.0b013e3280143226. PMID 17218796.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 "A comprehensive in vitro screening of d-, l-, and dl-threo-methylphenidate: an exploratory study". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 16 (6): 687–698. December 2006. doi:10.1089/cap.2006.16.687. PMID 17201613.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 "Chapter 6: Widely projecting systems: Monoamines, acetylcholine, and orexin". Molecular Neuropharmacology: A foundation for clinical neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2009. pp. 154–157. ISBN 9780071481274.

- ↑ "A randomized, controlled effectiveness trial of OROS-methylphenidate compared to usual care with immediate-release methylphenidate in attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder". The Canadian Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 13 (1): e50–e62. 2006. PMID 16456216. http://www.cjcp.ca/pdf/CJCP_05-012_e50.pdf.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 102.2 "Methylphenidate and its isomers: their role in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder using a transdermal delivery system". CNS Drugs 20 (9): 713–738. 2006. doi:10.2165/00023210-200620090-00002. PMID 16953648.

- ↑ "Neurotransmitter transporters and their impact on the development of psychopharmacology". British Journal of Pharmacology 147 (Suppl 1): S82–S88. January 2006. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706428. PMID 16402124.

- ↑ "Mechanism of action of methylphenidate: insights from PET imaging studies". Journal of Attention Disorders 6 (Suppl 1): S31–S43. 1 January 2002. doi:10.1177/070674370200601s05. PMID 12685517.

- ↑ "Meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of inhibition and attention in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: exploring task-specific, stimulant medication, and age effects". JAMA Psychiatry 70 (2): 185–198. February 2013. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.277. PMID 23247506.

- ↑ "Effect of psychostimulants on brain structure and function in ADHD: a qualitative literature review of magnetic resonance imaging-based neuroimaging studies". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 74 (9): 902–917. September 2013. doi:10.4088/JCP.12r08287. PMID 24107764.

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 "Meta-analysis of structural MRI studies in children and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder indicates treatment effects". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 125 (2): 114–126. February 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01786.x. PMID 22118249.

- ↑ "Dysfunctions in dopamine systems and ADHD: evidence from animals and modeling". Neural Plasticity 11 (1–2): 97–114. 2004. doi:10.1155/NP.2004.97. PMID 15303308.

- ↑ "Focalin XR". RxList. https://www.rxlist.com/focalin-xr-drug.htm#description.

- ↑ "Concerta XL 18 mg – 54 mg prolonged release tablets". eMC. http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/8380.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 "The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity". Journal of Neurochemistry 116 (2): 164–176. January 2011. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. PMID 21073468.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 "VMAT2: a dynamic regulator of brain monoaminergic neuronal function interacting with drugs of abuse". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1216 (1): 86–98. January 2011. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05906.x. PMID 21272013. Bibcode: 2011NYASA1216...86E.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 "Striatal dopamine neurotransmission: regulation of release and uptake". Basal Ganglia 6 (3): 123–148. August 2016. doi:10.1016/j.baga.2016.02.001. PMID 27141430.

- ↑ "Dexmethylphenidate hydrochloride in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 2 (4): 467–473. December 2006. doi:10.2147/nedt.2006.2.4.467. PMID 19412495.

- ↑ "The psychostimulant d-threo-(R,R)-methylphenidate binds as an agonist to the 5HT(1A) receptor". Die Pharmazie 64 (2): 123–125. February 2009. PMID 19322953.

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 "Relationship between psychostimulant-induced "high" and dopamine transporter occupancy". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 93 (19): 10388–10392. September 1996. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.19.10388. PMID 8816810. Bibcode: 1996PNAS...9310388V.

- ↑ "Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of bupropion for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence". Drug and Alcohol Dependence 96 (3): 222–232. August 2008. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.010. PMID 18468815.

- ↑ "Dopamine reuptake transporter (DAT) "inverse agonism" – a novel hypothesis to explain the enigmatic pharmacology of cocaine". Neuropharmacology 87: 19–40. December 2014. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.06.012. PMID 24953830.

- ↑ 119.0 119.1 "Neuropharmacological mechanisms underlying the neuroprotective effects of methylphenidate". Current Neuropharmacology 6 (4): 379–385. December 2008. doi:10.2174/157015908787386041. PMID 19587858.

- ↑ "Concerta". 1 October 2018. https://www.drugs.com/pro/concerta.html.

- ↑ "Methylphenidate hydrochloride given with or before breakfast: II. Effects on plasma concentration of methylphenidate and ritalinic acid". Pediatrics 72 (1): 56–59. July 1983. doi:10.1542/peds.72.1.56. PMID 6866592. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9gv7p39v. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ↑ "Cotempla XR-ODT- methylphenidate tablet, orally disintegrating". 1 July 2021. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=33f70f58-c871-42c8-8adb-345caeafefcd.

- ↑ "Quillivant XR- methylphenidate hydrochloride suspension, extended release". 30 June 2021. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=c2dc2109-44a6-4797-b04e-18761dd9d45a.

- ↑ "Bioavailability of modified-release methylphenidate: influence of high-fat breakfast when administered intact and when capsule content sprinkled on applesauce". Biopharmaceutics & Drug Disposition 24 (6): 233–243. September 2003. doi:10.1002/bdd.358. PMID 12973820.

- ↑ "Methylphenidate is stereoselectively hydrolyzed by human carboxylesterase CES1A1". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 310 (2): 469–476. August 2004. doi:10.1124/jpet.104.067116. PMID 15082749.

- ↑ Neuropathology of Drug Addictions and Substance Misuse. 3: General processes and mechanisms, prescription medications, caffeine and areca, polydrug misuse, emerging addictions, and non-drug addictions. Academic Press. 2016. p. 651. ISBN 9780128006771. https://books.google.com/books?id=Yu9eBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA651. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ↑ "Efficacy of stimulants for cognitive enhancement in non-attention deficit hyperactivity disorder youth: A systematic review". Addiction 109 (4): 547–557. April 2014. doi:10.1111/add.12460. PMID 24749160.

- ↑ "Conformational analysis of methylphenidate and its structural relationship to other dopamine reuptake blockers such as CFT". Pharmaceutical Research 12 (10): 1430–1434. October 1995. doi:10.1023/A:1016262815984. PMID 8584475.

- ↑ "Approaches to the Preparation of Enantiomerically Pure (2R,2′R)-(+)-threo-Methylphenidate Hydrochloride". Adv. Synth. Catal. 343 (5): 379–392. 2001. doi:10.1002/1615-4169(200107)343:5<379::AID-ADSC379>3.0.CO;2-4.

- ↑ "A Stereoselective Synthesis ofdl-threo-Methylphenidate: Preparation and Biological Evaluation of Novel Analogues". The Journal of Organic Chemistry 63 (26): 9628–9629. 1998. doi:10.1021/jo982214t.

- ↑ "Chemistry, design, and structure-activity relationship of cocaine antagonists". Chemical Reviews 100 (3): 925–1024. March 2000. doi:10.1021/cr9700538. PMID 11749256.

- ↑ Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (9th ed.). Seal Beach, CA: Biomedical Publications. 2011. pp. 1091–1093.

- ↑ 133.0 133.1 "The history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders 2 (4): 241–255. December 2010. doi:10.1007/s12402-010-0045-8. PMID 21258430.

- ↑ "Classics in chemical neuroscience: Methylphenidate". ACS Chem Neurosci 7 (8): 1030–1040. August 2016. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00199. PMID 27409720.

- ↑ Panizzon L (1944). "La preparazione di piridile piperidil-arilacetonitrili e di alcuni prodotti di trasformazione (Parte Ia)". Helvetica Chimica Acta 27: 1748–1756. doi:10.1002/hlca.194402701222.

- ↑ The 100 Most Important Chemical Compounds: A reference guide. ABC-CLIO. 1 January 2007. p. 178. ISBN 9780313337581. https://books.google.com/books?id=a4DuGVwyN6cC&q=named+ritalin+after+his+wife&pg=PA178. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ↑ 137.0 137.1 137.2 137.3 "Methylphenidate and its isomers: their role in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder using a transdermal delivery system". CNS Drugs 20 (9): 713–738. 2006. doi:10.2165/00023210-200620090-00002. PMID 16953648.

- ↑ "Ritalin, eine neuartige synthetische Verbindung mit spezifischer zentralerregender Wirkungskomponente" (in de). Klinische Wochenschrift 32 (19–20): 445–450. May 1954. doi:10.1007/BF01466968. PMID 13164273.

- ↑ "Psychostimulants and cognition: A continuum of behavioral and cognitive activation". Pharmacol Rev 66 (1): 193–221. 2014. doi:10.1124/pr.112.007054. PMID 24344115.

- ↑ Hartmann, M.; Panizzon, L., "Pyridine and piperidine compounds and process of making same", US patent 2507631, issued 16 May 1950, assigned to CIBA Pharmaceutical Products, Inc

- ↑ Rouietscji, R., "Process for the conversion of stereoisomers", US patent 2838519, issued 10 June 1958, assigned to CIBA Pharmaceutical Products, Inc

- ↑ Rouietscji, R., "Process for the conversion of stereoisomers", US patent 2957880, issued 25 October 1960, assigned to CIBA Pharmaceutical Products, Inc

- ↑ The 100 Most Important Chemical Compounds: A reference guide. ABC-CLIO. August 2007. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-313-33758-1. https://archive.org/details/100mostimportant0000myer. Retrieved 10 September 2010. "... named ritalin after his wife ..."

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Psychopharmacology. Berlin, DE / London, UK: Springer. 2010. p. 763. ISBN 978-3540686989.

- ↑ Ritalin and attention deficit disorder: History of its use, effects, and side effects (Report). 1995. http://www.crossinology.com/pdf/RITALINus.pdf. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ↑ "Benzedrine and dexedrine in the treatment of children's behavior disorders". Pediatrics 5 (1): 24–37. January 1950. doi:10.1542/peds.5.1.24. PMID 15404645.

- ↑ DEA Congressional Testimony (Report). U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. 16 May 2000. http://www.dea.gov/pubs/cngrtest/ct051600.htm. Retrieved 2 November 2007.

- ↑ "Drug Approval Package: Concerta (methylphenidate HCI) NDA #21-121". 24 December 1999. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2000/21-121_Concerta.cfm.

- ↑ "Newly Approved Drug Therapies (637) Concerta, Alza". http://www.centerwatch.com/drug-information/fda-approvals/drug-details.aspx?DrugID=637.

- ↑ "Narcotics monitoring board reports 66% increase in global consumption of methylphenidate". The Pharmaceutical Journal (Royal Pharmaceutical Society) 294 (7853). 4 March 2015. doi:10.1211/PJ.2015.20068042. https://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/news-and-analysis/news-in-brief/narcotics-monitoring-board-reports-66-increase-in-global-consumption-of-methylphenidate/20068042.article?firstPass=false. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ↑ "The Top 300 of 2021". https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Top300Drugs.aspx.

- ↑ "Methylphenidate - Drug Usage Statistics". https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Methylphenidate.

- ↑ 153.0 153.1 Application for inclusion to the 22nd expert committee on the selection and use of essential medicines: Methylphenidate hydrochloride (Report). World Health Organization. 8 December 2018. https://www.who.int/selection_medicines/committees/expert/22/applications/s24_methylphenidate.pdf. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ↑ Foquest: Methylphenidate hydrochloride controlled release capsules (vers. E). Product Monograph. Pickering, Ontario, Canada: Purdue Pharma. 1 March 2019. Submission Control Nr 214860. https://www.caddra.ca/wp-content/uploads/FOQUEST-Product-Monograph-E-01Mar2019.pdf. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ↑ "Dexmethylphenidate hydrochloride in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 2 (4): 467–473. December 2006. doi:10.2147/nedt.2006.2.4.467. PMID 19412495.

- ↑ "Education / training". University of Illinois. http://www.psych.uic.edu/docassist/ClinicalResources.html. "Ritalin‑SR, methylphenidate SR, Methylin ER, and Metadate ER are the same formulation and have the same drug delivery system"

- ↑

"New product: Sandoz methylphenidate SR 20 mg" (PDF) (Press release). Sandoz Canada Inc. 5 May 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

An alternative to Ritalin‑SR from Novartis

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedusfda-drugdb - ↑ "A review of long-acting medications for ADHD in Canada". Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 18 (4): 331–339. November 2009. PMID 19881943.

- ↑ "Aptensio XR Prescribing Information". http://www.aptensioxr.com/resources/full-prescribing-information.pdf.

- ↑ 161.0 161.1 161.2 161.3 161.4 "Methylphenidate". 26 July 2009. http://www.fpnotebook.com/peds/Pharm/Mthylphndt.htm.

- ↑ "Daytrana transdermal". WebMD. http://www.webmd.com/drugs/2/drug-144192/daytrana+transdermal/details.

- ↑ "Quillichew ER (methylphenidate HCl extended-release chewable tablets CII)". Pfizer Medical Information (pfizermedicalinformation.com) (Press release). U.S.: Pfizer. Archived from the original on 16 April 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ↑ "Concerta for Kids with ADHD". Pediatrics.about.com. 1 April 2003. http://pediatrics.about.com/cs/adhd/a/concerta.htm.

- ↑ "Concerta (methylphenidate extended-release tablets)". RxList. http://www.rxlist.com/concerta-drug.htm.

- ↑ "Metadate CD". http://adhd.emedtv.com/metadate-cd/metadate-cd.html.

- ↑ "Long-acting methylphenidate formulations in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review of head-to-head studies". BMC Psychiatry 13: 237. September 2013. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-13-237. PMID 24074240.

- ↑ "UK Report on Ritalin". p. 9. https://mhraproductsproduction.blob.core.windows.net/docs/4781baf366b1fafd0ea203962ccb54faadcdcfcc.

- ↑ Methylphenidate transdermal system (MTS) (safety summary). Noven Pharmaceuticals. 24 October 2005. NDA No. 21-514, Appendix 3. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/AC/05/briefing/2005-4195B1_01_04-Noven-Appendix-3.pdf. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ↑ "Methylphenidate and its isomers: their role in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder using a transdermal delivery system". CNS Drugs 20 (9): 713–738. 2006. doi:10.2165/00023210-200620090-00002. PMID 16953648. "Methylphenidate transdermal system: In attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children". Drugs 66 (8): 1117–1126. 2006. doi:10.2165/00003495-200666080-00007. PMID 16789796.

- ↑ Green List: Annex to the annual statistical report on psychotropic substances (form P) (Report) (23rd ed.). Vienna International Centre, Austria: International Narcotics Board. August 2003. (1.63 MB). http://www.incb.org/pdf/e/list/green.pdf. Retrieved 2 March 2006.

- ↑ "Poisons Standard 2012 as amended made under paragraph 52D(2)(a) of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989". Therapeutic Goods Administration. 27 November 2014. https://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2015C00043.

- ↑ Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (Report). Laws. Department of Justice, Government of Canada. 25 April 2017. S.C. 1996, c. 19. http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-38.8/. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ↑ "FIJI ISLANDS ILLICIT DRUGS CONTROL ACT 2004". https://www.health.gov.fj/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Fiji-Illicit-Drug-Act-2004.pdf.

- ↑ "TDAH : la prescription de méthylphénidate peut désormais être initiée en villexxxxxxxxx" (in fr). VIDAL. https://www.vidal.fr/actualites/27908-tdah-la-prescription-de-methylphenidate-peut-desormais-etre-initiee-en-villexxxxxxxxx.html.

- ↑ "Dangerous Drugs Ordinance". https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap134?xpid=ID_1438402701417_001.