Rust (programming language)

The official Rust logo | |

| Paradigms | |

|---|---|

| Designed by | Graydon Hoare |

| Developer | Rust Foundation |

| First appeared | May 15, 2015 |

| Typing discipline | |

| Implementation language | Rust |

| Platform | Cross-platform[note 1] |

| OS | Cross-platform[note 2] |

| License | MIT and Apache 2.0[note 3] |

| Filename extensions | .rs, .rlib |

| Influenced by | |

| Influenced | |

Rust is a multi-paradigm, general-purpose programming language that emphasizes performance, type safety, and concurrency. It enforces memory safety—meaning that all references point to valid memory—without a garbage collector. To simultaneously enforce memory safety and prevent data races, its "borrow checker" tracks the object lifetime of all references in a program during compilation. Rust was influenced by ideas from functional programming, including immutability, higher-order functions, and algebraic data types. It is popular for systems programming.[12][13][14]

Software developer Graydon Hoare created Rust as a personal project while working at Mozilla Research in 2006. Mozilla officially sponsored the project in 2009. In the years following the first stable release in May 2015, Rust was adopted by companies including Amazon, Discord, Dropbox, Google (Alphabet), Meta, and Microsoft. In December 2022, it became the first language other than C and assembly to be supported in the development of the Linux kernel.

Rust has been noted for its rapid adoption,[15] and has been studied in programming language theory research.[16][17][18]

History

Origins (2006–2012)

Rust grew out of a personal project begun in 2006 by Mozilla Research employee Graydon Hoare.[19] Mozilla began sponsoring the project in 2009 as a part of the ongoing development of an experimental browser engine called Servo,[20] which was officially announced by Mozilla in 2010.[21][22] During the same year, work shifted from the initial compiler written in OCaml to a self-hosting compiler based on LLVM written in Rust. The new Rust compiler successfully compiled itself in 2011.[20]

Evolution (2012–2019)

Rust's type system underwent significant changes between versions 0.2, 0.3, and 0.4. In version 0.2, which was released in March 2012, classes were introduced for the first time.[23] Four months later, version 0.3 added destructors and polymorphism, through the use of interfaces.[24] In October 2012, version 0.4 was released, which added traits as a means of inheritance. Interfaces were combined with traits and removed as a separate feature; and classes were replaced by a combination of implementations and structured types.[25]

Through early 2010s, memory management through the ownership system was gradually consolidated to prevent memory bugs. By 2013, Rust's garbage collector was removed, with the ownership rules in place.[19]

In January 2014, the editor-in-chief of Dr. Dobb's Journal, Andrew Binstock, commented on Rust's chances of becoming a competitor to C++, along with D, Go, and Nim (then Nimrod). According to Binstock, while Rust was "widely viewed as a remarkably elegant language", adoption slowed because it radically changed from version to version.[26] The first stable release, Rust 1.0, was announced on May 15, 2015.[27][28]

The development of the Servo browser engine continued alongside Rust's own growth. In September 2017, Firefox 57 was released as the first version that incorporated components from Servo, in a project named "Firefox Quantum".[29]

Mozilla layoffs and Rust Foundation (2020–present)

In August 2020, Mozilla laid off 250 of its 1,000 employees worldwide, as part of a corporate restructuring caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.[30][31] The team behind Servo was disbanded. The event raised concerns about the future of Rust, as some members of the team were active contributors to Rust.[32] In the following week, the Rust Core Team acknowledged the severe impact of the layoffs and announced that plans for a Rust foundation were underway. The first goal of the foundation would be to take ownership of all trademarks and domain names, and take financial responsibility for their costs.[33]

On February 8, 2021, the formation of the Rust Foundation was announced by its five founding companies (AWS, Huawei, Google, Microsoft, and Mozilla).[34][35] In a blog post published on April 6, 2021, Google announced support for Rust within the Android Open Source Project as an alternative to C/C++.[36]

On November 22, 2021, the Moderation Team, which was responsible for enforcing community standards and the Code of Conduct, announced their resignation "in protest of the Core Team placing themselves unaccountable to anyone but themselves".[37] In May 2022, the Rust Core Team, other lead programmers, and certain members of the Rust Foundation board implemented governance reforms in response to the incident.[38]

The Rust Foundation posted a draft for a new trademark policy on April 6, 2023, revising its rules on how the Rust logo and name can be used, which resulted in negative reactions from Rust users and contributors.[39]

Syntax and features

Rust's syntax is similar to that of C and C++,[40][41] although many of its features were influenced by functional programming languages.[42] Hoare described Rust as targeted at "frustrated C++ developers" and emphasized features such as safety, control of memory layout, and concurrency.[20] Safety in Rust includes the guarantees of memory safety, type safety, and lack of data races.

Hello World program

Below is a "Hello, World!" program in Rust. The Template:Rust keyword denotes a function, and the println! macro prints the message to standard output.[43] Statements in Rust are separated by semicolons.

fn main() {

println!("Hello, World!");

}

Keywords and control flow

In Rust, blocks of code are delimited by curly brackets, and control flow is implemented by keywords such as if, else, while, and for.[44] Pattern matching can be done using the Template:Rust keyword.[45] In the examples below, explanations are given in comments, which start with //.[46]

fn main() {

// Defining a mutable variable with 'let mut'

// Using the macro vec! to create a vector

let mut values = vec![1, 2, 3, 4];

for value in &values {

println!("value = {}", value);

}

if values.len() > 5 {

println!("List is longer than five items");

}

// Pattern matching

match values.len() {

0 => println!("Empty"),

1 => println!("One value"),

// pattern matching can use ranges of integers

2..=10 => println!("Between two and ten values"),

11 => println!("Eleven values"),

// A `_` pattern is called a "wildcard", it matches any value

_ => println!("Many values"),

};

// while loop with predicate and pattern matching using let

while let Some(value) = values.pop() {

println!("value = {value}"); // using curly brackets to format a local variable

}

}

Expression blocks

Rust is expression-oriented, with nearly every part of a function body being an expression, including control-flow operators.[47] The ordinary if expression is used instead of C's ternary conditional. With returns being implicit, a function does not need to end with a return expression; if the semicolon is omitted, the value of the last expression in the function is used as the return value,[48] as seen in the following recursive implementation of the factorial function:

fn factorial(i: u64) -> u64 {

if i == 0 {

1

} else {

i * factorial(i - 1)

}

}

The following iterative implementation uses the ..= operator to create an inclusive range:

fn factorial(i: u64) -> u64 {

(2..=i).product()

}

Closures

In Rust, anonymous functions are called closures.[49] They are defined using the following syntax:

|<parameter-name>: <type>| -> <return-type> { <body> };

For example:

let f = |x: i32| -> i32 { x * 2 };

With type inference, however, the compiler is able to infer the type of each parameter and the return type, so the above form can be written as:

let f = |x| { x * 2 };

With closures with a single expression (i.e. a body with one line) and implicit return type, the curly braces may be omitted:

let f = |x| x * 2;

Closures with no input parameter are written like so:

let f = || println!("Hello, world!");

Closures may be passed as input parameters of functions that expect a function pointer:

// A function which takes a function pointer as an argument and calls it with

// the value `5`.

fn apply(f: fn(i32) -> i32) -> i32 {

// No semicolon, to indicate an implicit return

f(5)

}

fn main() {

// Defining the closure

let f = |x| x * 2;

println!("{}", apply(f)); // 10

println!("{}", f(5)); // 10

}

However, one may need complex rules to describe how values in the body of the closure are captured. They are implemented using the Fn, FnMut, and FnOnce traits:[50]

Fn: the closure captures by reference (&T). They are used for functions that can still be called if they only have reference access (with&) to their environment.FnMut: the closure captures by mutable reference (&mut T). They are used for functions that can be called if they have mutable reference access (with&mut) to their environment.FnOnce: the closure captures by value (T). They are used for functions that are only called once.

With these traits, the compiler will capture variables in the least restrictive manner possible.[50] They help govern how values are moved around between scopes, which is largely important since Rust follows a lifetime construct to ensure values are "borrowed" and moved in a predictable and explicit manner.[51]

The following demonstrates how one may pass a closure as an input parameter using the Fn trait:

// A function that takes a value of type F (which is defined as

// a generic type that implements the `Fn` trait, e.g. a closure)

// and calls it with the value `5`.

fn apply_by_ref<F>(f: F) -> i32

where F: Fn(i32) -> i32

{

f(5)

}

fn main() {

let f = |x| {

println!("I got the value: {}", x);

x * 2

};

// Applies the function before printing its return value

println!("5 * 2 = {}", apply_by_ref(f));

}

// ~~ Program output ~~

// I got the value: 5

// 5 * 2 = 10

The previous function definition can also be shortened for convenience as follows:

fn apply_by_ref(f: impl Fn(i32) -> i32) -> i32 {

f(5)

}Types

Rust is strongly typed and statically typed. The types of all variables must be known at compilation time; assigning a value of a particular type to a differently typed variable causes a compilation error. Variables are declared with the keyword let, and type inference is used to determine their type.[52] Variables assigned multiple times must be marked with the keyword mut (short for mutable).[53]

The default integer type is Template:Rust, and the default floating point type is Template:Rust. If the type of a literal number is not explicitly provided, either it is inferred from the context or the default type is used.[54]

Primitive types

| Type | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Boolean value | ||

| Unsigned 8-bit integer (a byte) |

| |

| Signed integers, up to 128 bits | ||

| Unsigned integers, up to 128 bits | ||

| Pointer-sized integers (size depends on platform) | ||

| Floating-point numbers | ||

| ||

| UTF-8-encoded string slice, the primitive string type. It is usually seen in its borrowed form, Template:Rust. It is also the type of string literals, Template:Rust[56] | ||

| Array – collection of N objects of the same type T, stored in contiguous memory | ||

| Slice – a dynamically-sized view into a contiguous sequence[57] | ||

| Tuple – a finite heterogeneous sequence |

| |

| Never type (unreachable value) | Template:Rust |

Standard library

| Type | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| A pointer to a heap-allocated value[59] | let boxed: Box<u8> = Box::new(5); let val: u8 = *boxed; | |

| UTF-8-encoded strings (dynamic) | ||

| Platform-native strings[note 7] (borrowed[60] and dynamic[61]) | ||

| Paths (borrowed[62] and dynamic[63]) | ||

| C-compatible, null-terminated strings (borrowed[64] and dynamic[64]) | ||

| Dynamic arrays | ||

| Option type | ||

| Error handling using a result type | ||

| Reference counting pointer[65] | let five = Rc::new(5); let also_five = five.clone(); | |

| Atomic, thread-safe reference counting pointer[66] | let foo = Arc::new(vec![1.0, 2.0]); let a = foo.clone(); // a can be sent to another thread | |

| A mutable memory location[67] | let c = Cell::new(5); c.set(10); | |

Mutex<T>

|

A mutex lock for shared data[68] | let mutex = Mutex::new(0_u32); let _guard = mutex.lock(); |

| Readers–writer lock[69] | let lock = RwLock::new(5); let r1 = lock.read().unwrap(); | |

| A conditional monitor for shared data[70] | let (lock, cvar) = (Mutex::new(true), Condvar::new());

// As long as the value inside the `Mutex<bool>` is `true`, we wait.

let _guard = cvar.wait_while(lock.lock().unwrap(), |pending| { *pending }).unwrap();

| |

| Type that represents a span of time[71] | Duration::from_millis(1) // 1ms | |

| Hash table[72] | let mut player_stats = HashMap::new();

player_stats.insert("damage", 1);

player_stats.entry("health").or_insert(100);

| |

| B-tree[73] | let mut solar_distance = BTreeMap::from([

("Mercury", 0.4),

("Venus", 0.7),

]);

solar_distance.entry("Earth").or_insert(1.0);

|

Option values are handled using syntactic sugar, such as the if let construction, to access the inner value (in this case, a string):[74]

fn main() {

let name1: Option<&str> = None;

// In this case, nothing will be printed out

if let Some(name) = name1 {

println!("{name}");

}

let name2: Option<&str> = Some("Matthew");

// In this case, the word "Matthew" will be printed out

if let Some(name) = name2 {

println!("{name}");

}

}

Pointers

| Type | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| References (immutable and mutable) | ||

|

||

| A pointer to heap-allocated value

(or possibly null pointer if wrapped in option)[64] |

||

|

Rust does not use null pointers to indicate a lack of data, as doing so can lead to null dereferencing. Accordingly, the basic & and &mut references are guaranteed to not be null. Rust instead uses Option for this purpose: Some(T) indicates that a value is present, and None is analogous to the null pointer.[75] Option implements a "null pointer optimization", avoiding any spatial overhead for types that cannot have a null value (references or the NonZero types, for example).[76]

Unlike references, the raw pointer types *const and *mut may be null; however, it is impossible to dereference them unless the code is explicitly declared unsafe through the use of an unsafe block. Unlike dereferencing, the creation of raw pointers is allowed inside of safe Rust code.[77]

User-defined types

User-defined types are created with the struct or enum keywords. The struct keyword is used to denote a record type that groups multiple related values.[78] enums can take on different variants at runtime, with its capabilities similar to algebraic data types found in functional programming languages.[79] Both structs and enums can contain fields with different types.[80] Alternative names for the same type can be defined with the type keyword.[81]

The impl keyword can define methods for a user-defined type (data and functions are defined separately). Implementations fulfill a role similar to that of classes within other languages.[82]

Type conversion

Ownership and lifetimes

Rust's ownership system consists of rules that ensure memory safety without using a garbage collector. At compile time, each value must be attached to a variable called the owner of that value, and every value must have exactly one owner.[84] Values are moved between different owners through assignment or passing a value as a function parameter. Values can also be borrowed, meaning they are temporarily passed to a different function before being returned to the owner.[85] With these rules, Rust can prevent the creation and use of dangling pointers:[85][86]

fn print_string(s: String) {

println!("{}", s);

}

fn main() {

let s = String::from("Hello, World");

print_string(s); // s consumed by print_string

// s has been moved, so cannot be used any more

// another print_string(s); would result in a compile error

}

Because of these ownership rules, Rust types are known as linear or affine types, meaning each value can be used exactly once. This enforces a form of software fault isolation as the owner of a value is solely responsible for its correctness and deallocation.[87]

Lifetimes are usually an implicit part of all reference types in Rust. Each lifetime encompasses a set of locations in the code for which a variable is valid. For example, a reference to a local variable has a lifetime corresponding to the block it is defined in:[88]

fn main() {

let r = 9; // ------------------+- Lifetime 'a

// |

{ // |

let x = 5; // -+-- Lifetime 'b |

println!("r: {}, x: {}", r, x); // | |

} // | |

// |

println!("r: {}", r); // |

} // ------------------+

The borrow checker in the Rust compiler uses lifetimes to ensure that the values a reference points to remain valid. It also ensures that a mutable reference exists only if no immutable references exist at the same time.[89][90] In the example above, the subject of the reference (variable x) has a shorter lifetime than the lifetime of the reference itself (variable r), therefore the borrow checker errors, preventing x from being used from outside its scope.[91] Rust's memory and ownership system was influenced by region-based memory management in languages such as Cyclone and ML Kit.[4]

Rust defines the relationship between the lifetimes of the objects created and used by functions, using lifetime parameters, as a signature feature.[92]

When a stack or temporary variable goes out of scope, it is dropped by running its destructor. The destructor may be programmatically defined through the drop function. This technique enforces the so-called resource acquisition is initialization (RAII) design pattern, in which resources, such as file descriptors or network sockets, are tied to the lifetime of an object: when the object is dropped, the resource is closed.[93][94]

The example below parses some configuration options from a string and creates a struct containing the options. The struct only contains references to the data; so, for the struct to remain valid, the data referred to by the struct must be valid as well. The function signature for parse_config specifies this relationship explicitly. In this example, the explicit lifetimes are unnecessary in newer Rust versions, due to lifetime elision, which is an algorithm that automatically assigns lifetimes to functions if they are trivial.[95]

use std::collections::HashMap;

// This struct has one lifetime parameter, 'src. The name is only used within the struct's definition.

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Config<'src> {

hostname: &'src str,

username: &'src str,

}

// This function also has a lifetime parameter, 'cfg. 'cfg is attached to the "config" parameter, which

// establishes that the data in "config" lives at least as long as the 'cfg lifetime.

// The returned struct also uses 'cfg for its lifetime, so it can live at most as long as 'cfg.

fn parse_config<'cfg>(config: &'cfg str) -> Config<'cfg> {

let key_values: HashMap<_, _> = config

.lines()

.filter(|line| !line.starts_with('#'))

.filter_map(|line| line.split_once('='))

.map(|(key, value)| (key.trim(), value.trim()))

.collect();

Config {

hostname: key_values["hostname"],

username: key_values["username"],

}

}

fn main() {

let config = parse_config(

r#"hostname = foobar

username=barfoo"#,

);

println!("Parsed config: {:#?}", config);

}

Memory safety

Rust is designed to be memory safe. It does not permit null pointers, dangling pointers, or data races.[96][97][98] Data values can be initialized only through a fixed set of forms, all of which require their inputs to be already initialized.[99]

Unsafe code can subvert some of these restrictions, using the unsafe keyword.[77] Unsafe code may also be used for low-level functionality, such as volatile memory access, architecture-specific intrinsics, type punning, and inline assembly.[100]

Memory management

Rust does not use garbage collection. Memory and other resources are instead managed through the "resource acquisition is initialization" convention,[101] with optional reference counting. Rust provides deterministic management of resources, with very low overhead.[102] Values are allocated on the stack by default, and all dynamic allocations must be explicit.[103]

The built-in reference types using the & symbol do not involve run-time reference counting. The safety and validity of the underlying pointers is verified at compile time, preventing dangling pointers and other forms of undefined behavior.[104] Rust's type system separates shared, immutable references of the form &T from unique, mutable references of the form &mut T. A mutable reference can be coerced to an immutable reference, but not vice versa.[105]

Polymorphism

Generics

Rust's more advanced features include the use of generic functions. A generic function is given generic parameters, which allow the same function to be applied to different variable types. This capability reduces duplicate code[106] and is known as parametric polymorphism.

The following program calculates the sum of two things, for which addition is implemented using a generic function:

use std::ops::Add;

// sum is a generic function with one type parameter, T

fn sum<T>(num1: T, num2: T) -> T

where

T: Add<Output = T>, // T must implement the Add trait where addition returns another T

{

num1 + num2 // num1 + num2 is syntactic sugar for num1.add(num2) provided by the Add trait

}

fn main() {

let result1 = sum(10, 20);

println!("Sum is: {}", result1); // Sum is: 30

let result2 = sum(10.23, 20.45);

println!("Sum is: {}", result2); // Sum is: 30.68

}

At compile time, polymorphic functions like sum are instantiated with the specific types the code requires; in this case, sum of integers and sum of floats.

Generics can be used in functions to allow implementing a behavior for different types without repeating the same code. Generic functions can be written in relation to other generics, without knowing the actual type.[107]

Traits

Rust's type system supports a mechanism called traits, inspired by type classes in the Haskell language,[4] to define shared behavior between different types. For example, the Add trait can be implemented for floats and integers, which can be added; and the Display or Debug traits can be implemented for any type that can be converted to a string. Traits can be used to provide a set of common behavior for different types without knowing the actual type. This facility is known as ad hoc polymorphism.

Generic functions can constrain the generic type to implement a particular trait or traits; for example, an add_one function might require the type to implement Add. This means that a generic function can be type-checked as soon as it is defined. The implementation of generics is similar to the typical implementation of C++ templates: a separate copy of the code is generated for each instantiation. This is called monomorphization and contrasts with the type erasure scheme typically used in Java and Haskell. Type erasure is also available via the keyword dyn (short for dynamic).[108] Because monomorphization duplicates the code for each type used, it can result in more optimized code for specific-use cases, but compile time and size of the output binary are also increased.[109]

In addition to defining methods for a user-defined type, the impl keyword can be used to implement a trait for a type.[82] Traits can provide additional derived methods when implemented.[110] For example, the trait Iterator requires that the next method be defined for the type. Once the next method is defined, the trait can provide common functional helper methods over the iterator, such as map or filter.[111]

Traits follow the composition over inheritance design principle.[112] That is, traits cannot define fields themselves; they provide a restricted form of inheritance where methods can be defined and mixed in to implementations.

Trait objects

Rust traits are implemented using static dispatch, meaning that the type of all values is known at compile time; however, Rust also uses a feature known as trait objects to accomplish dynamic dispatch (also known as duck typing).[113] Dynamically dispatched trait objects are declared using the syntax dyn Tr where Tr is a trait. Trait objects are dynamically sized, therefore they must be put behind a pointer, such as Box.[114] The following example creates a list of objects where each object can be printed out using the Display trait:

use std::fmt::Display;

let v: Vec<Box<dyn Display>> = vec![

Box::new(3),

Box::new(5.0),

Box::new("hi"),

];

for x in v {

println!("{x}");

}

If an element in the list does not implement the Display trait, it will cause a compile-time error.[115]

Iterators

For loops in Rust work in a functional style as operations over an iterator type. For example, in the loop

for x in 0..100 {

f(x);

}

0..100 is a value of type Range which implements the Iterator trait; the code applies the function f to each element returned by the iterator. Iterators can be combined with functions over iterators like map, filter, and sum. For example, the following adds up all numbers between 1 and 100 that are multiples of 3:

(1..=100).filter(|&x| x % 3 == 0).sum()

Macros

It is possible to extend the Rust language using macros.

Declarative macros

A declarative macro (also called a "macro by example") is a macro that uses pattern matching to determine its expansion.[116][117]

Procedural macros

Procedural macros are Rust functions that run and modify the compiler's input token stream, before any other components are compiled. They are generally more flexible than declarative macros, but are more difficult to maintain due to their complexity.[118][119]

Procedural macros come in three flavors:

- Function-like macros

custom!(...) - Derive macros

#[derive(CustomDerive)] - Attribute macros

#[custom_attribute]

The println! macro is an example of a function-like macro. Theserde_derive macro[120] provides a commonly used library for generating code

for reading and writing data in many formats, such as JSON. Attribute macros are commonly used for language bindings, such as the extendr library for Rust bindings to R.[121]

The following code shows the use of the Serialize, Deserialize, and Debug-derived procedural macros

to implement JSON reading and writing, as well as the ability to format a structure for debugging.

use serde_json::{Serialize, Deserialize};

#[derive(Serialize, Deserialize, Debug)]

struct Point {

x: i32,

y: i32,

}

fn main() {

let point = Point { x: 1, y: 2 };

let serialized = serde_json::to_string(&point).unwrap();

println!("serialized = {}", serialized);

let deserialized: Point = serde_json::from_str(&serialized).unwrap();

println!("deserialized = {:?}", deserialized);

}

Variadic macros

Rust does not support variadic arguments in functions. Instead, it uses macros.[122]

macro_rules! calculate {

// The pattern for a single `eval`

(eval $e:expr) => {{

{

let val: usize = $e; // Force types to be integers

println!("{} = {}", stringify!{$e}, val);

}

}};

// Decompose multiple `eval`s recursively

(eval $e:expr, $(eval $es:expr),+) => {{

calculate! { eval $e }

calculate! { $(eval $es),+ }

}};

}

fn main() {

calculate! { // Look ma! Variadic `calculate!`!

eval 1 + 2,

eval 3 + 4,

eval (2 * 3) + 1

}

}

Rust is able to interact with C's variadic system via a c_variadic feature switch. As with other C interfaces, the system is considered unsafe to Rust.[123]Interface with C and C++

Rust has a foreign function interface (FFI) that can be used both to call code written in languages such as C from Rust and to call Rust code from those languages. As of 2023, a external library called CXX exists for calling to or from C++.[124] Rust and C differ in how they lay out structs in memory, so Rust structs may be given a #[repr(C)] attribute, forcing the same layout as the equivalent C struct.[125]

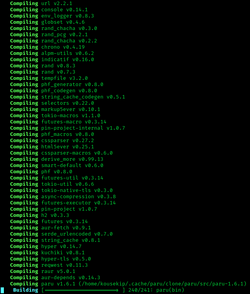

Components

The Rust ecosystem includes its compiler, its standard library, and additional components for software development. Component installation is typically managed by rustup, a Rust toolchain installer developed by the Rust project.[126]

Compiler

The Rust compiler is named rustc. Internally, rustc is a frontend to various backends that are used for further device-specific and platform-specific binary code files (e.g. ELF or WASM binary) generation (compilation). The most mature and most used backend in rustc is the LLVM intermediate representation (bytecode) compiler,[127][better source needed] but a Cranelift-based backend and a GCC-based backend are also available in nightly builds of the compiler.[128]

Standard library

The Rust standard library defines and implements many widely used custom data types, including core data structures such as Vec, Option, and HashMap, as well as smart pointer types. Rust also provides a way to exclude most of the standard library using the attribute Template:Rust; this enables applications, such as embedded devices, which want to remove dependency code or provide their own core data structures. Internally, the standard library is divided into three parts, core, alloc, and std, where std and alloc are excluded by Template:Rust.[129]

Cargo

Cargo is Rust's build system and package manager. It downloads, compiles, distributes, and uploads packages—called crates—that are maintained in an official registry. It also acts as a front-end for Clippy and other Rust components.[15]

By default, Cargo sources its dependencies from the user-contributed registry crates.io, but Git repositories and crates in the local filesystem, and other external sources can also be specified as dependencies.[130]

Rustfmt

Rustfmt is a code formatter for Rust. It formats whitespace and indentation to produce code in accordance with a common style, unless otherwise specified. It can be invoked as a standalone program, or from a Rust project through Cargo.[131]

Clippy

Clippy is Rust's built-in linting tool to improve the correctness, performance, and readability of Rust code. It was created in 2014[132][better source needed] and named after Microsoft Office's assistant, an anthropomorphized paperclip of the same name.[133] (As of 2024), it has more than 700 rules,[134][135] which can be browsed online and filtered by category.[136][137]

Versioning system

Following Rust 1.0, new features are developed in nightly versions which are released daily. During each six-week release cycle, changes to nightly versions are released to beta, while changes from the previous beta version are released to a new stable version.[138]

Every two or three years, a new "edition" is produced. Editions are released to allow making limited breaking changes, such as promoting await to a keyword to support async/await features. Crates targeting different editions can interoperate with each other, so a crate can upgrade to a new edition even if its callers or its dependencies still target older editions. Migration to a new edition can be assisted with automated tooling.[139]

IDE support

The most popular language server for Rust is Rust Analyzer, which officially replaced the original language server, RLS, in July 2022.[140] Rust Analyzer provides IDEs and text editors with information about a Rust project; basic features including autocompletion, and the display of compilation errors while editing.[141]

Performance

In general, Rust's memory safety guarantees do not impose a runtime overhead.[142] A notable exception is array indexing which is checked at runtime, though this often does not impact performance.[143] Since it does not perform garbage collection, Rust is often faster than other memory-safe languages.[144][145][146]

Rust provides two "modes": safe and unsafe. Safe mode is the "normal" one, in which most Rust is written. In unsafe mode, the developer is responsible for the code's memory safety, which is useful for cases where the compiler is too restrictive.[147]

Many of Rust's features are so-called zero-cost abstractions, meaning they are optimized away at compile time and incur no runtime penalty.[148] The ownership and borrowing system permits zero-copy implementations for some performance-sensitive tasks, such as parsing.[149] Static dispatch is used by default to eliminate method calls, with the exception of methods called on dynamic trait objects.[150] The compiler also uses inline expansion to eliminate function calls and statically-dispatched method invocations.[151]

Since Rust utilizes LLVM, any performance improvements in LLVM also carry over to Rust.[152] Unlike C and C++, Rust allows for reordering struct and enum elements[153] to reduce the sizes of structures in memory, for better memory alignment, and to improve cache access efficiency.[154]

Adoption

Rust has been used in software spanning across different domains. Rust was initially funded by Mozilla as part of developing Servo, an experimental parallel browser engine, in collaboration with Samsung.[155] Components from the Servo engine were later incorporated in the Gecko browser engine underlying Firefox.[156] In January 2023, Google (Alphabet) announced support for third party Rust libraries in Chromium and consequently in the ChromeOS code base.[157]

Rust is used in several backend software projects of large web services. OpenDNS, a DNS resolution service owned by Cisco, uses Rust internally.[158][159] Amazon Web Services began developing projects in Rust as early as 2017,[160] including Firecracker, a virtualization solution;[161] Bottlerocket, a Linux distribution and containerization solution;[162] and Tokio, an asynchronous networking stack.[163] Microsoft Azure IoT Edge, a platform used to run Azure services on IoT devices, has components implemented in Rust.[164] Microsoft also uses Rust to run containerized modules with WebAssembly and Kubernetes.[165] Cloudflare, a company providing content delivery network services uses Rust for its firewall pattern matching engine.[166][167]

In operating systems, the Rust for Linux project was begun in 2021 to add Rust support to the Linux kernel.[168] Support for Rust (along with support for C and Assembly language) was officially added in version 6.1.[169] Microsoft announced in 2020 that parts of Microsoft Windows are being rewritten in Rust. (As of 2023), DWriteCore, a system library for text layout and glyph render, has about 152,000 lines of Rust code and about 96,000 lines of C++ code, and saw a performance increase of 5 to 15 percent in some cases.[170] Google announced support for Rust in the Android operating system also in 2021.[171][172] Other operating systems written in Rust include Redox, a "Unix-like" operating system and microkernel,[173] and Theseus, an experimental operating system with modular state management.[174][175] Rust is also used for command-line tools and operating system components, including stratisd, a file system manager[176][177] and COSMIC, a desktop environment by System76.[178][179]

In web development, the npm package manager started using Rust in production in 2019.[180][181][182] Deno, a secure runtime for JavaScript and TypeScript, is built with V8, Rust, and Tokio.[183] Other notable adoptions in this space include Ruffle, an open-source SWF emulator,[184] and Polkadot, an open source blockchain and cryptocurrency platform.[185]

Discord, an instant messaging social platform uses Rust for portions of its backend, as well as client-side video encoding.[186] In 2021, Dropbox announced their use of Rust for a screen, video, and image capturing service.[187] Facebook (Meta) used Rust for Mononoke, a server for the Mercurial version control system.[188]

In the 2023 Stack Overflow Developer Survey, 13% of respondents had recently done extensive development in Rust.[189] The survey also named Rust the "most loved programming language" every year from 2016 to 2023 (inclusive), based on the number of developers interested in continuing to work in the same language.[190][note 8] In 2023, Rust was the 6th "most wanted technology", with 31% of developers not currently working in Rust expressing an interest in doing so.[189]

Community

Rust Foundation

| |

| Formation | February 8, 2021 |

|---|---|

| Founders | |

| Type | Nonprofit organization |

| Location | |

| Shane Miller | |

Executive Director | Rebecca Rumbul |

| Website | foundation |

The Rust Foundation is a non-profit membership organization incorporated in United States , with the primary purposes of backing the technical project as a legal entity and helping to manage the trademark and infrastructure assets.[192][41]

It was established on February 8, 2021, with five founding corporate members (Amazon Web Services, Huawei, Google, Microsoft, and Mozilla).[193] The foundation's board is chaired by Shane Miller.[194] Starting in late 2021, its Executive Director and CEO is Rebecca Rumbul.[195] Prior to this, Ashley Williams was interim executive director.[196]

Governance teams

The Rust project is composed of teams that are responsible for different subareas of the development. The compiler team develops, manages, and optimizes compiler internals; and the language team designs new language features and helps implement them. The Rust project website lists 9 top-level teams (As of January 2024).[197] Representatives among teams form the Leadership council, which oversees the Rust project as a whole.[198]

See also

- Comparison of programming languages

- History of programming languages

- List of programming languages

- List of programming languages by type

Notes

- ↑ Including build tools, host tools, and standard library support for x86-64, ARM, MIPS, RISC-V, WebAssembly, i686, AArch64, PowerPC, and s390x.[1]

- ↑ Including Windows, Linux, macOS, FreeBSD, NetBSD, and Illumos. Host build tools on Android, iOS, Haiku, Redox, and Fuchsia are not officially shipped; these operating systems are supported as targets.[1]

- ↑ Third-party dependencies, e.g., LLVM or MSVC, are subject to their own licenses.[2][3]

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 This literal uses an explicit suffix, which is not needed when type can be inferred from the context

- ↑ Interpreted as Template:Rust by default, or inferred from the context

- ↑ Type inferred from the context

- ↑ On Unix systems, this is often UTF-8 strings without an internal 0 byte. On Windows, this is UTF-16 strings without an internal 0 byte. Unlike these, Template:Rust and Template:Rust are always valid UTF-8 and can contain internal zeros.

- ↑ That is, among respondents who have done "extensive development work [with Rust] in over the past year" (13.05%), Rust had the largest percentage who also expressed interest to "work in [Rust] over the next year" (84.66%).[189]

References

Book sources

- Gjengset, Jon (2021) (in en). Rust for Rustaceans (1st ed.). No Starch Press. ISBN 9781718501850. OCLC 1277511986. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1277511986.

- Klabnik, Steve; Nichols, Carol (2019-08-12) (in en). The Rust Programming Language (Covers Rust 2018). No Starch Press. ISBN 978-1-7185-0044-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=0Vv6DwAAQBAJ.

- Blandy, Jim; Orendorff, Jason; Tindall, Leonora F. S. (2021) (in en). Programming Rust: Fast, Safe Systems Development (2nd ed.). O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-1-4920-5254-8. OCLC 1289839504. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1289839504.

- McNamara, Tim (2021) (in en). Rust in Action. Manning Publications. ISBN 978-1-6172-9455-6. OCLC 1153044639. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1153044639.

- Klabnik, Steve; Nichols, Carol (2023). The Rust programming language (2nd ed.). No Starch Press. ISBN 978-1-7185-0310-6. OCLC 1363816350. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1363816350.

Others

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Platform Support". https://doc.rust-lang.org/rustc/platform-support.html.

- ↑ "The Rust Programming Language". The Rust Programming Language. 19 October 2022. https://github.com/rust-lang/rust/blob/master/COPYRIGHT.

- ↑ "Rust Legal Policies". https://www.rust-lang.org/policies/licenses.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 "Influences - The Rust Reference". https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/influences.html.

- ↑ "Uniqueness Types". https://blog.rust-lang.org/2016/08/10/Shape-of-errors-to-come.html. ""Those of you familiar with the Elm style may recognize that the updated --explain messages draw heavy inspiration from the Elm approach.""

- ↑ "Uniqueness Types". http://docs.idris-lang.org/en/latest/reference/uniqueness-types.html. ""They are inspired by ... ownership types and borrowed pointers in the Rust programming language.""

- ↑ "Microsoft opens up Rust-inspired Project Verona programming language on GitHub". ZDNet. https://www.zdnet.com/article/microsoft-opens-up-rust-inspired-project-verona-programming-language-on-github/.

- ↑ Jaloyan, Georges-Axel (19 October 2017). "Safe Pointers in SPARK 2014". arXiv:1710.07047 [cs.PL].

- ↑ Lattner, Chris. "Chris Lattner's Homepage". http://nondot.org/sabre/.

- ↑ "V documentation (Introduction)" (in en). https://github.com/vlang/v/blob/master/doc/docs.md#introduction.

- ↑ Yegulalp, Serdar (2016-08-29). "New challenger joins Rust to topple C language" (in en). https://www.infoworld.com/article/3113083/new-challenger-joins-rust-to-upend-c-language.html.

- ↑ Eshwarla, Prabhu (2020-12-24) (in en). Practical System Programming for Rust Developers: Build fast and secure software for Linux/Unix systems with the help of practical examples. Packt Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-80056-201-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=eEUREAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Blandy, Jim; Orendorff, Jason (2017-11-21) (in en). Programming Rust: Fast, Safe Systems Development. O'Reilly Media, Inc.. ISBN 978-1-4919-2725-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=h8c_DwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Blanco-Cuaresma, Sergi; Bolmont, Emeline (2017-05-30). "What can the programming language Rust do for astrophysics?" (in en). Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union 12 (S325): 341–344. doi:10.1017/S1743921316013168. ISSN 1743-9213. Bibcode: 2017IAUS..325..341B. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/proceedings-of-the-international-astronomical-union/article/what-can-the-programming-language-rust-do-for-astrophysics/B51B6DF72B7641F2352C05A502F3D881.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Perkel, Jeffrey M. (2020-12-01). "Why scientists are turning to Rust" (in en). Nature 588 (7836): 185–186. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-03382-2. PMID 33262490. Bibcode: 2020Natur.588..185P. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-03382-2. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ↑ "Computer Scientist proves safety claims of the programming language Rust" (in en). https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/610682.

- ↑ Jung, Ralf; Jourdan, Jacques-Henri; Krebbers, Robbert; Dreyer, Derek (2017-12-27). "RustBelt: securing the foundations of the Rust programming language". Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages 2 (POPL): 66:1–66:34. doi:10.1145/3158154. https://doi.org/10.1145/3158154. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ↑ Jung, Ralf (2020). Understanding and evolving the Rust programming language (PhD thesis). Saarland University. doi:10.22028/D291-31946. Archived from the original on March 8, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Thompson, Clive (2023-02-14). "How Rust went from a side project to the world's most-loved programming language" (in en). https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/02/14/1067869/rust-worlds-fastest-growing-programming-language/.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Avram, Abel (2012-08-03). "Interview on Rust, a Systems Programming Language Developed by Mozilla". InfoQ. http://www.infoq.com/news/2012/08/Interview-Rust.

- ↑ Asay, Matt (2021-04-12). "Rust, not Firefox, is Mozilla's greatest industry contribution" (in en-US). https://www.techrepublic.com/article/rust-not-firefox-is-mozillas-greatest-industry-contribution/.

- ↑ Hoare, Graydon (7 July 2010). "Project Servo". Mozilla Annual Summit 2010. Whistler, Canada. http://venge.net/graydon/talks/intro-talk-2.pdf. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ↑ Hoare, Graydon (2012-03-29). "[rust-dev Rust 0.2 released"]. https://mail.mozilla.org/pipermail/rust-dev/2012-March/001511.html.

- ↑ Hoare, Graydon (2012-07-12). "[rust-dev Rust 0.3 released"]. https://mail.mozilla.org/pipermail/rust-dev/2012-July/002087.html.

- ↑ Hoare, Graydon (October 15, 2012). "[rust-dev Rust 0.4 released"]. https://mail.mozilla.org/pipermail/rust-dev/2012-October/002489.html.

- ↑ Binstock, Andrew (January 7, 2014). "The Rise And Fall of Languages in 2013". https://www.drdobbs.com/jvm/the-rise-and-fall-of-languages-in-2013/240165192.

- ↑ "Version History". https://github.com/rust-lang/rust/blob/master/RELEASES.md.

- ↑ The Rust Core Team (May 15, 2015). "Announcing Rust 1.0". http://blog.rust-lang.org/2015/05/15/Rust-1.0.html.

- ↑ Lardinois, Frederic (2017-09-29). "It's time to give Firefox another chance" (in en-US). https://techcrunch.com/2017/09/29/its-time-to-give-firefox-another-chance/.

- ↑ Cimpanu, Catalin (2020-08-11). "Mozilla lays off 250 employees while it refocuses on commercial products". ZDNet. https://www.zdnet.com/article/mozilla-lays-off-250-employees-while-it-refocuses-on-commercial-products/.

- ↑ Cooper, Daniel (2020-08-11). "Mozilla lays off 250 employees due to the pandemic". https://www.engadget.com/mozilla-firefox-250-employees-layoffs-151324924.html.

- ↑ Tung, Liam. "Programming language Rust: Mozilla job cuts have hit us badly but here's how we'll survive" (in en). ZDNet. https://www.zdnet.com/article/programming-language-rust-mozilla-job-cuts-have-hit-us-badly-but-heres-how-well-survive/.

- ↑ "Laying the foundation for Rust's future". 2020-08-18. https://blog.rust-lang.org/2020/08/18/laying-the-foundation-for-rusts-future.html.

- ↑ "Hello World!" (in en). 2020-02-08. https://foundation.rust-lang.org/news/2021-02-08-hello-world/.

- ↑ "Mozilla Welcomes the Rust Foundation". 2021-02-09. https://blog.mozilla.org/blog/2021/02/08/mozilla-welcomes-the-rust-foundation.

- ↑ Amadeo, Ron (2021-04-07). "Google is now writing low-level Android code in Rust" (in en-us). https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2021/04/google-is-now-writing-low-level-android-code-in-rust/.

- ↑ Anderson, Tim (2021-11-23). "Entire Rust moderation team resigns" (in en). https://www.theregister.com/2021/11/23/rust_moderation_team_quits/.

- ↑ "Governance Update" (in en). https://blog.rust-lang.org/inside-rust/2022/05/19/governance-update.html.

- ↑ Claburn, Thomas (2023-04-17). "Rust Foundation apologizes for trademark policy confusion" (in en). https://www.theregister.com/2023/04/17/rust_foundation_apologizes_trademark_policy/.

- ↑ Proven, Liam (2019-11-27). "Rebecca Rumbul named new CEO of The Rust Foundation" (in en). https://www.theregister.com/2021/11/19/rust_foundation_ceo/. ""Both are curly bracket languages, with C-like syntax that makes them unintimidating for C programmers.""

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Brandon Vigliarolo (2021-02-10). "The Rust programming language now has its own independent foundation" (in en-US). https://www.techrepublic.com/article/the-rust-programming-language-now-has-its-own-independent-foundation/.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, p. 263.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 49–57.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 104–109.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, p. 49.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 50–53.

- ↑ Tyson, Matthew (2022-03-03). "Rust programming for Java developers" (in en). https://www.infoworld.com/article/3651362/rust-programming-for-java-developers.html.

- ↑ "Closures - Rust By Example". https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/rust-by-example/fn/closures.html.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 "As input parameters - Rust By Example". https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/rust-by-example/fn/closures/input_parameters.html.

- ↑ "Lifetimes - Rust By Example". https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/rust-by-example/scope/lifetime.html.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 24.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 36–38.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ "str – Rust". https://doc.rust-lang.org/beta/std/primitive.str.html.

- ↑ "slice – Rust". https://doc.rust-lang.org/beta/std/primitive.slice.html.

- ↑ "Tuples". https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/primitives/tuples.html.

- ↑ "std::boxed – Rust". https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/boxed/index.html.

- ↑ "OsStr in std::ffi – Rust". https://doc.rust-lang.org/beta/std/ffi/struct.OsStr.html.

- ↑ "OsString in std::ffi – Rust". https://doc.rust-lang.org/beta/std/ffi/struct.OsString.html.

- ↑ "Path in std::path – Rust". https://doc.rust-lang.org/beta/std/path/struct.Path.html.

- ↑ "PathBuf in std::path – Rust". https://doc.rust-lang.org/beta/std/path/struct.PathBuf.html.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 "std::boxed – Rust". https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/boxed/index.html.

- ↑ "Rc in std::rc – Rust". https://doc.rust-lang.org/beta/std/rc/struct.Rc.html.

- ↑ "Arc in std::sync – Rust". https://doc.rust-lang.org/beta/std/sync/struct.Arc.html.

- ↑ "Cell in std::cell – Rust". https://doc.rust-lang.org/beta/std/cell/struct.Cell.html#.

- ↑ "Mutex in std::sync – Rust". https://doc.rust-lang.org/beta/std/sync/struct.Mutex.html.

- ↑ "RwLock in std::sync – Rust". https://doc.rust-lang.org/beta/std/sync/struct.RwLock.html.

- ↑ "Condvar in std::sync – Rust". https://doc.rust-lang.org/beta/std/sync/struct.Condvar.html.

- ↑ "Duration in std::time – Rust". https://doc.rust-lang.org/beta/std/time/struct.Duration.html.

- ↑ "HashMap in std::collections – Rust". https://doc.rust-lang.org/beta/std/collections/struct.HashMap.html.

- ↑ "BTreeMap in std::collections – Rust". https://doc.rust-lang.org/beta/std/collections/struct.BTreeMap.html.

- ↑ McNamara 2021.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 101–104.

- ↑ "std::option - Rust". https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/option/index.html#representation.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 418–427.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, p. 83.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, p. 97.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 98–101.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 438–440.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 93.

- ↑ "Casting - Rust By Example". https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/types/cast.html.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 59–61.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 63–68.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Balasubramanian, Abhiram; Baranowski, Marek S.; Burtsev, Anton; Panda, Aurojit; Rakamarić, Zvonimir; Ryzhyk, Leonid (2017-05-07). "System Programming in Rust". Proceedings of the 16th Workshop on Hot Topics in Operating Systems. HotOS '17. New York, NY, US: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 156–161. doi:10.1145/3102980.3103006. ISBN 978-1-4503-5068-6. https://doi.org/10.1145/3102980.3103006. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, p. 194.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 75,134.

- ↑ Shamrell-Harrington, Nell. "The Rust Borrow Checker – a Deep Dive" (in en). https://www.infoq.com/presentations/rust-borrow-checker/.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 194-195.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 192–204.

- ↑ "Drop in std::ops – Rust". https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/ops/trait.Drop.html.

- ↑ Gomez, Guillaume; Boucher, Antoni (2018). "RAII". Rust programming by example (First ed.). Birmingham, UK: Packt Publishing. p. 358. ISBN 9781788390637.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 201–203.

- ↑ Rosenblatt, Seth (2013-04-03). "Samsung joins Mozilla's quest for Rust". CNET. http://reviews.cnet.com/8301-3514_7-57577639/samsung-joins-mozillas-quest-for-rust/.

- ↑ Brown, Neil (2013-04-17). "A taste of Rust". https://lwn.net/Articles/547145/.

- ↑ "Races – The Rustonomicon". https://doc.rust-lang.org/nomicon/races.html.

- ↑ "The Rust Language FAQ". 2015. http://static.rust-lang.org/doc/master/complement-lang-faq.html.

- ↑ McNamara 2021, p. 139, 376–379, 395.

- ↑ "RAII – Rust By Example". https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/scope/raii.html.

- ↑ "Abstraction without overhead: traits in Rust". https://blog.rust-lang.org/2015/05/11/traits.html.

- ↑ "Box, stack and heap". https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/rust-by-example/std/box.html.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 70–75.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, p. 323.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 171–172.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 171–172,205.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 181,182.

- ↑ Gjengset 2021, p. 25.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 182–184.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 281–283.

- ↑ Milanesi, Carlo (2018). Beginning Rust: from novice to professional. Berkeley, CA: Apress. p. 283. ISBN 978-1-4842-3468-6. OCLC 1029604209. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1029604209.

- ↑ "Using Trait Objects That Allow for Values of Different Types – The Rust Programming Language". https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch17-02-trait-objects.html.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 441–442.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 379–380.

- ↑ "Macros By Example". https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/macros-by-example.html.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 446–448.

- ↑ "Procedural Macros". https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/procedural-macros.html.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 449–455.

- ↑ "Serde Derive". https://serde.rs/derive.html.

- ↑ "extendr_api – Rust". https://extendr.github.io/extendr/extendr_api/index.html.

- ↑ "Variadics". https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/macros/variadics.html.

- ↑ "2137-variadic". https://rust-lang.github.io/rfcs/2137-variadic.html.

- ↑ "Safe Interoperability between Rust and C++ with CXX" (in en). 2020-12-06. https://www.infoq.com/news/2020/12/cpp-rust-interop-cxx/.

- ↑ "Type layout – The Rust Reference". https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/type-layout.html#the-c-representation.

- ↑ 樽井, 秀人 (2022-07-13). "「Rust」言語のインストーラー「Rustup」が「Visual Studio 2022」の自動導入に対応/Windows/Mac/Linux、どのプラットフォームでも共通の手順でお手軽セットアップ" (in ja). https://forest.watch.impress.co.jp/docs/news/1424702.html.

- ↑ Yegulalp, Serdar (2020-03-11). "What is LLVM? The power behind Swift, Rust, Clang, and more" (in en). https://www.infoworld.com/article/3247799/what-is-llvm-the-power-behind-swift-rust-clang-and-more.html.

- ↑ "Overview of the compiler – Rust Compiler Development Guide". https://rustc-dev-guide.rust-lang.org/overview.html#code-generation.

- ↑ Gjengset 2021, p. 213-215.

- ↑ Simone, Sergio De (2019-04-18). "Rust 1.34 Introduces Alternative Registries for Non-Public Crates" (in en). https://www.infoq.com/news/2019/04/rust-1.34-additional-registries.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 511–512.

- ↑ "Create README.md · rust-lang/rust-clippy@507dc2b" (in en). https://github.com/rust-lang/rust-clippy/commit/507dc2b7ec30cf94554b441d4fcb1ce113f98a16.

- ↑ "24 days of Rust: Day 1: Cargo subcommands". https://zsiciarz.github.io/24daysofrust/book/vol2/day1.html.

- ↑ Clippy, The Rust Programming Language, 2023-11-30, https://github.com/rust-lang/rust-clippy, retrieved 2023-11-30

- ↑ "Clippy Lints". https://rust-lang.github.io/rust-clippy/master/index.html.

- ↑ "ALL the Clippy Lints". https://rust-lang.github.io/rust-clippy/.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, pp. 513–514.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2019, Appendix G – How Rust is Made and "Nightly Rust"

- ↑ Blandy, Orendorff & Tindall 2021, pp. 176–177.

- ↑ Anderson, Tim (2022-07-05). "Rust team releases 1.62, sets end date for deprecated language server" (in en-GB). https://devclass.com/2022/07/05/rust-team-releases-1-62-sets-end-date-for-deprecated-language-server/.

- ↑ Klabnik & Nichols 2023, p. 623.

- ↑ McNamara 2021, p. 11.

- ↑ Popescu, Natalie; Xu, Ziyang; Apostolakis, Sotiris; August, David I.; Levy, Amit (2021-10-15). "Safer at any speed: automatic context-aware safety enhancement for Rust". Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages 5 (OOPSLA): Section 2. doi:10.1145/3485480. https://doi.org/10.1145/3485480. ""We observe a large variance in the overheads of checked indexing: 23.6% of benchmarks do report significant performance hits from checked indexing, but 64.5% report little-to-no impact and, surprisingly, 11.8% report improved performance ... Ultimately, while unchecked indexing can improve performance, most of the time it does not."".

- ↑ Anderson, Tim. "Can Rust save the planet? Why, and why not" (in en). https://www.theregister.com/2021/11/30/aws_reinvent_rust/.

- ↑ Balasubramanian, Abhiram; Baranowski, Marek S.; Burtsev, Anton; Panda, Aurojit; Rakamarić, Zvonimir; Ryzhyk, Leonid (2017-05-07). "System Programming in Rust" (in en). Proceedings of the 16th Workshop on Hot Topics in Operating Systems. Whistler BC Canada: ACM. pp. 156–161. doi:10.1145/3102980.3103006. ISBN 978-1-4503-5068-6. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3102980.3103006.

- ↑ Yegulalp, Serdar (2021-10-06). "What is the Rust language? Safe, fast, and easy software development" (in en). https://www.infoworld.com/article/3218074/what-is-rust-safe-fast-and-easy-software-development.html.

- ↑ Wróbel, Krzysztof (April 11, 2022). "Rust projects – why large IT companies use Rust?". https://codilime.com/blog/rust-projects-why-large-it-companies-use-rust/.

- ↑ McNamara 2021, p. 19, 27.

- ↑ Couprie, Geoffroy (2015). "Nom, A Byte oriented, streaming, Zero copy, Parser Combinators Library in Rust". 2015 IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops. pp. 142–148. doi:10.1109/SPW.2015.31. ISBN 978-1-4799-9933-0. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7163218.

- ↑ McNamara 2021, p. 20.

- ↑ "Code generation – The Rust Reference". https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/attributes/codegen.html.

- ↑ "How Fast Is Rust?". https://doc.rust-lang.org/1.0.0/complement-lang-faq.html#how-fast-is-rust?.

- ↑ Farshin, Alireza; Barbette, Tom; Roozbeh, Amir; Maguire Jr, Gerald Q.; Kostić, Dejan (2021). "PacketMill: Toward per-Core 100-GBPS networking" (in en). Proceedings of the 26th ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems. pp. 1–17. doi:10.1145/3445814.3446724. ISBN 9781450383172. https://dlnext.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3445814.3446724. Retrieved 2022-07-12. "... While some compilers (e.g., Rust) support structure reordering [82], C & C++ compilers are forbidden to reorder data structures (e.g., struct or class) [74] ..."

- ↑ "Type layout". https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/type-layout.html.

- ↑ Lardinois, Frederic (2015-04-03). "Mozilla And Samsung Team Up To Develop Servo, Mozilla's Next-Gen Browser Engine For Multicore Processors". TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2013/04/03/mozilla-and-samsung-collaborate-on-servo-mozillas-next-gen-browser-engine-for-tomorrows-multicore-processors/.

- ↑ Keizer, Gregg (2016-10-31). "Mozilla plans to rejuvenate Firefox in 2017" (in en). https://www.computerworld.com/article/3137050/mozilla-plans-to-rejuvenate-firefox-in-2017.html.

- ↑ "Supporting the Use of Rust in the Chromium Project" (in en). https://security.googleblog.com/2023/01/supporting-use-of-rust-in-chromium.html.

- ↑ Shankland, Stephen (2016-07-12). "Firefox will get overhaul in bid to get you interested again" (in en). CNET. https://www.cnet.com/tech/services-and-software/firefox-mozilla-gets-overhaul-in-a-bid-to-get-you-interested-again/.

- ↑ Security Research Team (2013-10-04). "ZeroMQ: Helping us Block Malicious Domains in Real Time" (in en-US). https://umbrella.cisco.com/blog/zeromq-helping-us-block-malicious-domains.

- ↑ "How our AWS Rust team will contribute to Rust's future successes" (in en-US). 2021-03-03. https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/opensource/how-our-aws-rust-team-will-contribute-to-rusts-future-successes/.

- ↑ "Firecracker – Lightweight Virtualization for Serverless Computing" (in en-US). 2018-11-26. https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/aws/firecracker-lightweight-virtualization-for-serverless-computing/.

- ↑ "Announcing the General Availability of Bottlerocket, an open source Linux distribution built to run containers" (in en-US). 2020-08-31. https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/opensource/announcing-the-general-availability-of-bottlerocket-an-open-source-linux-distribution-purpose-built-to-run-containers/.

- ↑ "Why AWS loves Rust, and how we'd like to help" (in en-US). 2020-11-24. https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/opensource/why-aws-loves-rust-and-how-wed-like-to-help/.

- ↑ Nichols, Shaun (27 June 2018). "Microsoft's next trick? Kicking things out of the cloud to Azure IoT Edge" (in en). https://www.theregister.co.uk/2018/06/27/microsofts_next_cloud_trick_kicking_things_out_of_the_cloud_to_azure_iot_edge/.

- ↑ Tung, Liam. "Microsoft: Why we used programming language Rust over Go for WebAssembly on Kubernetes app" (in en). ZDNet. https://www.zdnet.com/article/microsoft-why-we-used-programming-language-rust-over-go-for-webassembly-on-kubernetes-app/.

- ↑ "How we made Firewall Rules" (in en). 2019-03-04. http://blog.cloudflare.com/how-we-made-firewall-rules/.

- ↑ "Enjoy a slice of QUIC, and Rust!" (in en). 2019-01-22. http://blog.cloudflare.com/enjoy-a-slice-of-quic-and-rust/.

- ↑ Anderson, Tim (2021-12-07). "Rusty Linux kernel draws closer with new patch" (in en). https://www.theregister.com/2021/12/07/rusty_linux_kernel_draws_closer/.

- ↑ "A first look at Rust in the 6.1 kernel [LWN.net"]. https://lwn.net/Articles/910762/.

- ↑ Claburn, Thomas (2023-04-27). "Microsoft is rewriting core Windows libraries in Rust" (in en). https://www.theregister.com/2023/04/27/microsoft_windows_rust/.

- ↑ "Rust in the Android platform" (in en). https://security.googleblog.com/2021/04/rust-in-android-platform.html.

- ↑ Amadeo, Ron (2021-04-07). "Google is now writing low-level Android code in Rust" (in en-us). https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2021/04/google-is-now-writing-low-level-android-code-in-rust/.

- ↑ Yegulalp, Serdar. "Rust's Redox OS could show Linux a few new tricks". InfoWorld. http://www.infoworld.com/article/3046100/open-source-tools/rusts-redox-os-could-show-linux-a-few-new-tricks.html.

- ↑ Anderson, Tim (2021-01-14). "Another Rust-y OS: Theseus joins Redox in pursuit of safer, more resilient systems" (in en). https://www.theregister.com/2021/01/14/rust_os_theseus/.

- ↑ Boos, Kevin; Liyanage, Namitha; Ijaz, Ramla; Zhong, Lin (2020) (in en). Theseus: an Experiment in Operating System Structure and State Management. pp. 1–19. ISBN 978-1-939133-19-9. https://www.usenix.org/conference/osdi20/presentation/boos.

- ↑ Sei, Mark (10 October 2018). "Fedora 29 new features: Startis now officially in Fedora". https://www.marksei.com/fedora-29-new-features-startis/.

- ↑ Proven, Liam (2022-07-12). "Oracle Linux 9 released, with some interesting additions" (in en). https://www.theregister.com/2022/07/12/oracle_linux_9/.

- ↑ Patel, Pratham (January 14, 2022). "I Tried System76's New Rust-based COSMIC Desktop!". It's FOSS News. https://news.itsfoss.com/system76-rust-cosmic-desktop/.

- ↑ "Pop!_OS by System76" (in en). System76, Inc.. https://pop.system76.com/.

- ↑ "NPM Adopted Rust to Remove Performance Bottlenecks" (in en). https://www.infoq.com/news/2019/03/rust-npm-performance/.

- ↑ Lyu, Shing (2020), Lyu, Shing, ed., "Welcome to the World of Rust" (in en), Practical Rust Projects: Building Game, Physical Computing, and Machine Learning Applications (Berkeley, CA: Apress): pp. 1–8, doi:10.1007/978-1-4842-5599-5_1, ISBN 978-1-4842-5599-5, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4842-5599-5_1, retrieved 2023-11-29

- ↑ Lyu, Shing (2021), Lyu, Shing, ed., "Rust in the Web World" (in en), Practical Rust Web Projects: Building Cloud and Web-Based Applications (Berkeley, CA: Apress): pp. 1–7, doi:10.1007/978-1-4842-6589-5_1, ISBN 978-1-4842-6589-5, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4842-6589-5_1, retrieved 2023-11-29

- ↑ Hu, Vivian (2020-06-12). "Deno Is Ready for Production" (in en). https://www.infoq.com/news/2020/06/deno-1-ready-production/.

- ↑ Abrams, Lawrence (2021-02-06). "This Flash Player emulator lets you securely play your old games" (in en-us). https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/software/this-flash-player-emulator-lets-you-securely-play-your-old-games/.

- ↑ "Ethereum Blockchain Killer Goes By Unassuming Name of Polkadot". Bloomberg L.P.. October 17, 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-10-17/ethereum-blockchain-killer-goes-by-unassuming-name-of-polkadot.

- ↑ Howarth, Jesse (2020-02-04). "Why Discord is switching from Go to Rust". https://discord.com/blog/why-discord-is-switching-from-go-to-rust.

- ↑ The Dropbox Capture Team. "Why we built a custom Rust library for Capture" (in en). https://dropbox.tech/application/why-we-built-a-custom-rust-library-for-capture.

- ↑ "A brief history of Rust at Facebook" (in en-US). 2021-04-29. https://engineering.fb.com/2021/04/29/developer-tools/rust/.

- ↑ 189.0 189.1 189.2 "Stack Overflow Developer Survey 2023". https://survey.stackoverflow.co/2023/.

- ↑ Claburn, Thomas (2022-06-23). "Linus Torvalds says Rust is coming to the Linux kernel" (in en). https://www.theregister.com/2022/06/23/linus_torvalds_rust_linux_kernel/.

- ↑ "Getting Started". https://www.rust-lang.org/learn/get-started#ferris.

- ↑ Tung, Liam (2021-02-08). "The Rust programming language just took a huge step forwards" (in en). ZDNet. https://www.zdnet.com/article/the-rust-programming-language-just-took-a-huge-step-forwards/.

- ↑ Krill, Paul. "Rust language moves to independent foundation". InfoWorld. https://www.infoworld.com/article/3606774/rust-language-moves-to-independent-foundation.html.

- ↑ Vaughan-Nichols, Steven J. (9 April 2021). "AWS's Shane Miller to head the newly created Rust Foundation". ZDNet. https://www.zdnet.com/article/awss-shane-miller-to-head-the-newly-created-rust-foundation/.

- ↑ Vaughan-Nichols, Steven J. (17 November 2021). "Rust Foundation appoints Rebecca Rumbul as executive director". ZDNet. https://www.zdnet.com/article/rust-foundation-appoints-rebecca-rumbul-as-executive-director/.

- ↑ "The Rust programming language now has its own independent foundation" (in en). February 10, 2021. https://www.techrepublic.com/article/the-rust-programming-language-now-has-its-own-independent-foundation/.

- ↑ "Governance" (in en-US). https://www.rust-lang.org/governance.

- ↑ "Introducing the Rust Leadership Council" (in en). https://blog.rust-lang.org/2023/06/20/introducing-leadership-council.html.

Further reading

- Blandy, Jim; Orendorff, Jason; Tindall, Leonora F. S. (2021-07-06) (in en). Programming Rust: Fast, Safe Systems Development. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-1-4920-5259-3.

External links

|