Medicine:Chronic fatigue syndrome

| Chronic fatigue syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Myalgic encephalomyelitis/ chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS),[1] myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), post-viral fatigue syndrome (PVFS), chronic fatigue immune dysfunction syndrome (CFIDS), systemic exertion intolerance disease (SEID), others[2]:20 |

| |

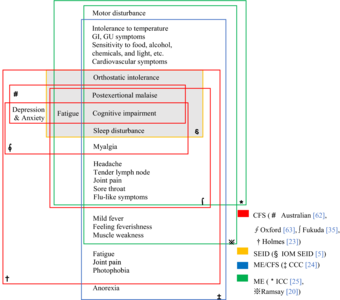

| Chart of the symptoms of CFS according to various definitions | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology, rehabilitation medicine, endocrinology, infectious disease, neurology, immunology, internal medicine, paediatrics, other specialists in ME/CFS[3] |

| Symptoms | Worsening of symptoms with activity, long-term fatigue, others[1] |

| Usual onset | 10 to 30 years old[4] |

| Duration | Often for years[5] |

| Causes | Unknown[1] |

| Risk factors | Female sex, virus and bacterial infections, blood relatives with the illness, major injury, bodily response to severe stress and others[6][7]:1–2 |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[1] |

| Treatment | Symptomatic[8][9] |

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), also called myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) or ME/CFS, is a complex, debilitating, long-term medical condition. The root cause(s) of the disease are unknown and the mechanisms are not fully understood.[12] Distinguishing core symptoms are lengthy exacerbations or flare-ups of the illness following ordinary minor physical or mental activity, known as post-exertional malaise (PEM);[13][14] greatly diminished capacity to accomplish tasks that were routine before the illness; and sleep disturbances.[13][15][1][5][2]:7 The Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) diagnostic criteria also require at least one of the following: (1) Orthostatic intolerance (difficulty sitting and standing upright) or (2) impaired memory or attention. Frequently and variably, other common symptoms occur involving numerous body systems, and chronic pain is very common.[15][16] The often incapacitating fatigue in CFS is different from that caused by normal strenuous ongoing exertion, is not significantly relieved by rest, and is not due to a previous medical condition.[15] Diagnosis is based on the person's symptoms because no confirmed diagnostic test is available.[17]

Proposed mechanisms include biological, genetic, epigenetic, infectious, and physical or psychological stress affecting the biochemistry of the body.[6][18] Persons with CFS may recover or improve over time, but some will become severely affected and disabled for an extended period.[19] No therapies or medications are approved to treat the cause of the illness; treatment is aimed at alleviation of symptoms.[8][20] The CDC recommends pacing (personal activity management) to keep mental and physical activity from making symptoms worse.[8] Limited evidence suggests that counseling,[21] personalized activity management,[20] and the use of rintatolimod help improve some patients' functional abilities.

About 1% of primary-care patients have CFS; estimates of incidence vary widely because various epidemiological studies have used dissimilar definitions.[11][17][10] It has been estimated that 836,000 to 2.5 million Americans and 250,000 to 1,250,000 people in the United Kingdom have CFS.[1][22] CFS occurs 1.5 to 2 times as often in women as in men.[11] It most commonly affects adults between ages 40 and 60 years;[23] it can occur at other ages, including childhood.[24] Other studies suggest that about 0.5% of children have CFS, and that it is more common in adolescents than in younger children.[2]:182[24] Chronic fatigue syndrome is a major cause of school absence.[2]:183 CFS significantly reduces health, happiness, productivity, and can also cause socio-emotional disruptions such as loneliness and alienation.[25]

There is controversy over many aspects of the disorder. Various physicians, researchers, and patient advocates promote different names and diagnostic criteria. Results of studies of proposed causes and treatments are often poor or contradictory.[26]

Signs and symptoms

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends these criteria for diagnosis:[15]

- Greatly lowered ability to do activities that were usual before the illness. This drop in activity level occurs along with fatigue and must last six months or longer.

- Worsening of symptoms after physical or mental activity that would not have caused a problem before the illness. The amount of activity that might aggravate the illness is difficult for a person to predict, and the decline often presents 12 to 48 hours after the activity.[27] The 'relapse', or 'crash', may last days, weeks or longer. This is known as post-exertional malaise (PEM).

- Sleep problems; people may still feel weary after full nights of sleep, or may struggle to stay awake, fall asleep or stay asleep.

Additionally, one of the following symptoms must be present:[15]

- Problems with thinking and memory (cognitive dysfunction, sometimes described as "brain fog")

- While standing or sitting upright; lightheadedness, dizziness, weakness, fainting or vision changes may occur (orthostatic intolerance)

Other common symptoms

Many, but not all people with ME/CFS report:[15]

- Muscle pain, joint pain without swelling or redness, and headache

- Tender lymph nodes in the neck or armpits

- Sore throat

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Chills and night sweats

- Allergies and sensitivities to foods, odors, chemicals, lights, or noise

- Shortness of breath

- Irregular heartbeat

Increased sensitivity to sensory stimuli and pain have also been observed in CFS.[19][28]

The CDC recommends that people with symptoms of CFS consult a physician to rule out other illnesses, which may be treatable.[29]

Onset

The onset of CFS may be gradual or sudden.[2] When it begins suddenly, it often follows an episode of infectious-like symptoms or a known infection, and between 20 and 80% of patients report an infectious-like onset.[2](p158)[30] When gradual, the illness may begin over the course of months or years with no apparent trigger.[31] Studies disagree as to which pattern is more common.[2]:158:181 CFS may also occur after physical trauma such as a car accident or surgery.[31]

Physical functioning

CFS often causes significant disability, but the degree can vary greatly.[1][31] Some people with mild CFS may lead relatively normal lives with vigilant energy management, while moderately affected patients may be unable to work or spend much time upright. People with severe CFS are generally housebound or bedbound, and may be unable to care for themselves.[31]

The majority of people with CFS have significant difficulty engaging in work, school, and family activities for extended periods of time.[15][31] An estimated 75% are unable to work because of their illness, and about 25% are housebound or bedridden for long periods, often decades.[2]:32[5][32] In one review on employment status, more than half of CFS patients were on disability benefits or temporary sick leave, and less than a fifth worked full-time.[33] In children, CFS is a major cause of school absence.[2]:183 According to a 1996 study by McCully et al, people with CFS report critical reductions in levels of physical activity, and according to a 2009 study, patients exhibit a reduction in the complexity of their activities.[34][35] Many people with CFS also experience strongly disabling chronic pain.[36]

Symptoms can fluctuate over time, making the condition difficult to manage. Persons who feel better for a period may overextend their activities, triggering post-exertional malaise and a worsening of symptoms.[27] Severity may also change over time, with periods of worsening, improvement or remission sometimes occurring.[31]

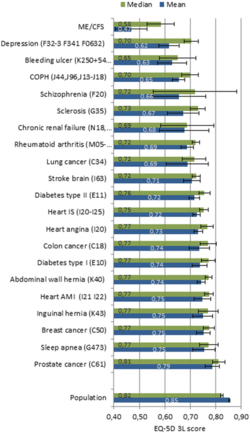

People with CFS have decreased quality of life according to the SF-36 questionnaire, especially in the domains of vitality, physical functioning, general health, physical role, and social functioning. However, their scores in the "role emotional" and mental health domains were not substantially lower than healthy controls.[37] A 2015 study found that people with CFS had lower health-related quality of life than 20 other chronic conditions, including multiple sclerosis, kidney failure, and lung cancer.[38]

Cognitive functioning

Cognitive dysfunction is one of the most disabling aspects of CFS due to its negative impact on occupational and social functioning. 50 to 80% of people with CFS are estimated to have serious problems with cognition.[39] Cognitive symptoms are mainly due to deficits in attention, memory, and reaction time. Measured cognitive abilities are found to be below projected normal values and likely to affect day-to-day activities, causing increases in common mistakes, forgetting scheduled tasks, or having difficulty responding when spoken to.[40]

Simple and complex information-processing speed and functions entailing working memory over long time periods are moderately to extensively impaired. These deficits are generally consistent with the patient's perceptions. Perceptual abilities, motor speed, language, reasoning, and intelligence do not appear to be significantly altered. Patients who report poorer health status tend to also report more severe cognitive trouble, and better physical functioning is associated with less visuoperceptual difficulty and fewer language-processing complaints.[40](p24)

Inconsistencies of subjective and observed values of cognitive dysfunction reported across multiple studies are likely caused by a number of factors. Differences of research participants' cognitive abilities pre- and post-illness onset are naturally variable and are difficult to measure because of a lack of specialized analytical tools that can consistently quantify the specific cognitive difficulties in CFS.[40]

Cause

The cause of CFS is unknown.[37][41] Both genetic and environmental factors are believed to contribute, but the genetic component is unlikely to be a single gene.[37] Problems with the nervous and immune systems, and energy metabolism, may be factors.[41] CFS is a biological disease, not a psychiatric or psychological condition,[42][37] and is not caused by deconditioning.[37][43] However, the biological abnormalities found in research are not sensitive or specific enough for diagnosis.[37](p1437)

Because the illness often follows a known or apparent viral illness, various infectious agents have been proposed, but a single cause has not been found.[44][2][37] Hypothesized infections include mononucleosis, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, human herpesvirus 6, and Lyme disease. Inflammation may be involved.[45] CFS has been observed to develop after mononucleosis and gastroenteritis.[46]

Risk factors

All ages, ethnic groups, and income levels are susceptible to the illness. The CDC states that while Caucasians may be diagnosed more frequently than other races in America,[5] the illness is at least as prevalent among African Americans and Hispanics.[23] A 2009 meta-analysis found that Asian Americans (Odds ratio: 0.097; 95%; Confidence interval: 0.004 - 0.65) have a much lower risk of CFS than White Americans, while Native Americans (OR: 11.5; 95% CI: 1.08 - 56.4) have a higher (probably a much higher) risk and African Americans (OR: 2.95; 95% CI: 0.69 - 10.4) probably have a higher risk. The review acknowledged that studies and data were limited.[47]

More women than men get CFS.[5] A large 2020 meta-analysis estimated that between 1.5 and 2.0 times more cases are women. The review acknowledged that different case definitions and diagnostic methods within datasets yielded a wide range of prevalence rates.[11] The CDC estimates CFS occurs up to four times more often in women than in men.[23] The illness can occur at any age, but has the highest prevalence in people aged 40 to 60.[23] CFS is less prevalent among children and adolescents than among adults.[24]

People with affected relatives appear to be more likely to get ME/CFS, implying the existence of genetic risk factors. Results of genetic studies have been largely contradictory or unreplicated. One study found an association with mildly deleterious mitochondrial DNA variants, and another found an association with certain variants of human leukocyte antigen genes.[14]

Viral and other infections

Post-viral fatigue syndrome (PVFS) or post-viral syndrome describes a type of chronic fatigue syndrome that occurs following a viral infection.[30] One review found higher Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) antibody activity in patients with CFS, and that a subset were likely to have increased EBV activity compared to controls.[48] Viral infection is a significant risk factor for CFS, with one study finding 22% of people with EBV experience fatigue six months later, and 9% having strictly defined CFS.[49] A systematic review found that fatigue severity was the main predictor of prognosis in CFS, and did not identify psychological factors linked to prognosis.[50] A review of long COVID research found half of those affected met diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS.[51]

Another review found that risk factors for developing CFS after mononucleosis, dengue fever, or Q-fever included longer bed-rest during the illness, poorer pre-illness physical fitness, attributing symptoms to physical illness, belief that a long recovery time is needed, as well as pre-infection distress and fatigue.[52] The same review found biological factors such as CD4 and CD8 activation and liver inflammation are predictors of sub-acute fatigue but not CFS.[52]

A study analyzing the relationship between diagnostic labels and prognosis found that patients diagnosed with ME had the worst prognosis, and that patients with PVFS had the best. According to a review, it is unclear whether this was because people labeled with ME had a more severe or persistent illness, or because being labelled with ME adversely affects prognosis.[53] The National Academy of Medicine report says it is a misconception that diagnosing ME/CFS worsens prognosis, and that accurate diagnosis is key to appropriate management.[2](p222)(p235)

Pathophysiology

ME/CFS is associated with changes in several areas, including the nervous, immune, and endocrine systems.[12][54] Reported neurological differences include altered brain structure and metabolism, and autonomic nervous system dysfunction.[54] Observed immunological changes include decreased natural killer cell activity, increased cytokines, and slightly increased levels of certain antibodies.[12] Endocrine differences, such as modestly low cortisol and HPA axis dysregulation, have been noted as well.[12] Impaired energy production and the possibility of autoimmunity are other areas of interest.[41]

Neurological

A range of neurological structural and functional abnormalities is found in people with CFS, including lowered metabolism at the brain stem and reduced blood flow to cortical areas of the brain; these differences are consistent with neurological illness, but not depression or psychological illness.[7] The World Health Organization classes chronic fatigue syndrome as a central nervous system disease.[55]

Some neuroimaging studies have observed prefrontal and brainstem hypometabolism; however, sample size was limited.[54] Neuroimaging studies in persons with CFS have identified changes in brain structure and correlations with various symptoms. Results were not consistent across the neuroimaging brain structure studies, and more research is needed to resolve the discrepancies found between the disparate studies.[56][54]

Tentative evidence suggests a relationship between autonomic nervous system dysfunction and diseases such as CFS, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, and interstitial cystitis. However, it is unknown if this relationship is causative.[57] Reviews of CFS literature have found autonomic abnormalities such as decreased sleep efficiency, increased sleep latency, decreased slow wave sleep, and abnormal heart rate response to tilt table tests, suggesting a role of the autonomic nervous system in CFS. However, these results were limited by inconsistency.[58][59][60]

Central sensitization, or increased sensitivity to sensory stimuli such as pain have been observed in CFS. Sensitivity to pain increases after exertion, which is opposite to the normal pattern.[28]

Immunological

Immunological abnormalities are frequently observed in those with CFS. Decreased NK cell activity is found more often in people with CFS and this correlates with severity of symptoms.[6][61] People with CFS have an abnormal response to exercise, including increased production of complement products, increased oxidative stress combined with decreased antioxidant response, and increased Interleukin 10, and TLR4, some of which correlates with symptom severity.[62] Increased levels of cytokines have been proposed to account for the decreased ATP production and increased lactate during exercise;[63][64] however, the elevations of cytokine levels are inconsistent in specific cytokine, albeit frequently found.[2][65] Similarities have been drawn between cancer and CFS with regard to abnormal intracellular immunological signaling. Abnormalities observed include hyperactivity of Ribonuclease L, a protein activated by IFN, and hyperactivity of NF-κB.[66]

Endocrine

Evidence points to abnormalities in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis) in some, but not all, persons with CFS, which may include slightly low cortisol levels,[67] a decrease in the variation of cortisol levels throughout the day, decreased responsiveness of the HPA axis, and a high serotonergic state, which can be considered to be a "HPA axis phenotype" that is also present in some other conditions, including post-traumatic stress disorder and some autoimmune conditions.[68] It is unclear whether or not decreased cortisol levels of the HPA axis plays a primary role as a cause of CFS,[69][70][71] or has a secondary role in the continuation or worsening of symptoms later in the illness.[72] In most healthy adults, the cortisol awakening response shows an increase in cortisol levels averaging 50% in the first half-hour after waking. In people with CFS, this increase apparently is significantly less, but methods of measuring cortisol levels vary, so this is not certain.[73]

Autoimmunity

Autoimmunity has been proposed to be a factor in CFS, but there are only a few relevant findings so far. There are a subset of patients with increased B cell activity and autoantibodies, possibly as a result of decreased NK cell regulation or viral mimicry.[74] In 2015, a large German study found 29% of ME/CFS patients had elevated autoantibodies to M3 and M4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors as well as to ß2 adrenergic receptors.[75][76][77] A 2016 Australian study found that ME/CFS patients had significantly greater numbers of single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with the gene encoding for M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors.[78][non-primary source needed]

Energy metabolism

Studies have observed mitochondrial abnormalities in cellular energy production, but recent focus has concentrated on secondary effects that may result in aberrant mitochondrial function because inherent problems with the mitochondria structure or genetics have not been replicated.[79]

Diagnosis

No characteristic laboratory abnormalities are approved to diagnose CFS; while physical abnormalities can be found, no single finding is considered sufficient for diagnosis.[80][7] Blood, urine, and other tests are used to rule out other conditions that could be responsible for the symptoms.[81][82][2] The CDC states that a medical history should be taken and a mental and physical examination should be done to aid diagnosis.[81]

Diagnostic tools

The CDC recommends considering the questionnaires and tools described in the 2015 Institute of Medicine report, which include:[83]

- The Chalder Fatigue Scale

- Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory

- Fisk Fatigue Impact Scale

- The Krupp Fatigue Severity Scale

- DePaul Symptom Questionnaire

- CDC Symptom Inventory for CFS

- Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS)

- SF-36 / RAND-36[2]:270

A two-day cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET) is not necessary for diagnosis, although lower readings on the second day may be helpful in supporting a claim for social security disability. A two-day CPET cannot be used to rule out chronic fatigue syndrome.[2]:216

Definitions

Many sets of diagnostic criteria for CFS have been proposed. Required symptoms vary, with post-exertional malaise, fatigue, cognitive impairment, and sleep disruption being the most commonly cited. Notable definitions include:[84][85]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definition (1994),[86] the most widely used clinical and research description of CFS,[18] is also called the Fukuda definition and is a revision of the Holmes or CDC 1988 scoring system.[87] The 1994 criteria require the presence of four or more symptoms beyond fatigue, while the 1988 criteria require six to eight.[88]

- The 2003 Canadian consensus criteria[89] state: "A patient with ME/CFS will meet the criteria for fatigue, post-exertional malaise and/or fatigue, sleep dysfunction, and pain; have two or more neurological/cognitive manifestations and one or more symptoms from two of the categories of autonomic, neuroendocrine, and immune manifestations; and the illness persists for at least 6 months".

- The Myalgic Encephalomyelitis International Consensus Criteria (ICC) published in 2011 is based on the Canadian working definition and has an accompanying primer for clinicians[90][7] The ICC does not have a six months waiting time for diagnosis. The ICC requires post-exertional neuroimmune exhaustion (PENE) which has similarities with post-exertional malaise, plus at least three neurological symptoms, at least one immune or gastrointestinal or genitourinary symptom, and at least one energy metabolism or ion transportation symptom. Unrefreshing sleep or sleep dysfunction, headaches or other pain, and problems with thinking or memory, and sensory or movement symptoms are all required under the neurological symptoms criterion.[90] According to the ICC, patients with post-exertional neuroimmune exhaustion but only partially meeting the criteria should be given the diagnosis of atypical myalgic encephalomyelitis.[7]

- The 2015 definition by the National Academy of Medicine (then referred to as the "Institute of Medicine") is not a definition of exclusion (differential diagnosis is still required).[2] "Diagnosis requires that the patient have the following three symptoms: 1) A substantial reduction or impairment in the ability to engage in pre-illness levels of occupational, educational, social, or personal activities, that persists for more than 6 months and is accompanied by fatigue, which is often profound, is of new or definite onset (not lifelong), is not the result of ongoing excessive exertion, and is not substantially alleviated by rest, and 2) post-exertional malaise* 3) Unrefreshing sleep*; At least one of the two following manifestations is also required: 1) Cognitive impairment* 2) Orthostatic intolerance" and notes that "*Frequency and severity of symptoms should be assessed. The diagnosis of ME/CFS should be questioned if patients do not have these symptoms at least half the time with moderate, substantial, or severe intensity."[2]

The 2021 UK NICE guidelines employ a definition of ME/CFS that requires severe fatigue, post-exertional malaise, unrefreshing sleep or sleep disturbance, and cognitive difficulties.[91]

Differential diagnosis

Certain medical conditions can cause chronic fatigue and must be ruled out before a diagnosis of CFS can be given. Hypothyroidism, anemia,[92] coeliac disease (that can occur without gastrointestinal symptoms),[93] diabetes and certain psychiatric disorders are a few of the diseases that must be ruled out if the patient presents with appropriate symptoms.[91][86][92] Other diseases, listed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, include infectious diseases (such as Epstein–Barr virus, influenza, HIV infection, tuberculosis, Lyme disease), neuroendocrine diseases (such as thyroiditis, Addison's disease, adrenal insufficiency, Cushing's disease), hematologic diseases (such as occult malignancy, lymphoma), rheumatologic diseases (such as fibromyalgia, polymyalgia rheumatica, Sjögren's syndrome, lupus, giant-cell arteritis, polymyositis, dermatomyositis), psychiatric diseases (such as bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, delusional disorders, dementia, anorexia/bulimia nervosa), neuropsychologic diseases (such as obstructive sleep apnea, narcolepsy,[41] parkinsonism, multiple sclerosis), and others (such as nasal obstruction from allergies, sinusitis, anatomic obstruction, autoimmune diseases, cancer, chronic hepatitis, some chronic illness, alcohol or other substance abuse, pharmacologic side effects, heavy metal exposure and toxicity, marked body weight fluctuation).[92]

Like CFS, fibromyalgia causes muscle pain, severe fatigue and sleep disturbances. The presence of allodynia (abnormal pain responses to mild stimulation) and extensive tender points in specific locations differentiates fibromyalgia from CFS, although the two diseases often co-occur.[94] Ehlers–Danlos syndromes (EDS) may also have similar symptoms.[95] Medications can also cause side effects that mimic symptoms of CFS.[29]

Depressive symptoms, if seen in CFS, may be differentially diagnosed from primary depression by the absence of anhedonia, decreased motivation, or guilt; and the presence of bodily symptoms such as sore throat, swollen lymph nodes, and post-exertional malaise.[92]

Management

There is no approved pharmacological treatment, therapy or cure for ME/CFS, although some symptoms can be treated or managed.[8][91] According to the CDC, pacing, or managing one's activities to stay within their energy limits, can reduce episodes of post-exertional malaise. Addressing sleep problems with good sleep hygiene, or medication if required, may be beneficial. Chronic pain is common in ME/CFS, and the CDC recommends consulting with a pain management specialist if over-the-counter painkillers are insufficient. The debilitating nature of ME/CFS can cause depression or other psychological problems, which should be treated accordingly. For cognitive impairment, adaptations like organizers and calendars may be helpful. Comorbid conditions are common and should be treated if present.[8]

According to the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), graded exercise therapy (GET) is not an appropriate treatment for ME/CFS. CBT might be offered to help a person manage the difficulties of dealing with chronic illness, but not as a cure for ME/CFS.[91]

The CDC recommends a strategy treating the most disabling symptom first, and the NICE guideline specifies the need for shared decision-making between patients and medical teams.[8] NICE recognized that symptoms of severe ME/CFS may be misunderstood as neglect or abuse and recommends assessment for safeguarding of persons suspected of having ME/CFS be evaluated by professionals with experience and understanding of the illness. Clinical management varies widely, with many patients receiving combinations of therapies.[96](p9)

Prior to publication of the NICE 2021 guideline, Andrew Goddard, president of the Royal College of Physicians, stated there was concern NICE did not adequately consider the experts' support and evidence of the benefits of GET and CBT, and urged they be included in the guideline. Various ME/CFS patient groups disputed the benefits of the therapies and stated that GET can make the illness more severe.[97][98]

Comorbid conditions that may interact with and worsen ME/CFS symptoms care are common, and appropriate medical intervention for these conditions may be beneficial. The most commonly diagnosed include fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, depression, anxiety, allergies, and chemical sensitivities.[99]

Pacing

Pacing, or activity management, is an illness management strategy based on the observation that symptoms tend to increase following mental or physical exertion,[8] and was recommended for CFS in the 1980s.[100] It is now commonly used as a management strategy in chronic illnesses and in chronic pain.[101]

Its two forms are symptom-contingent pacing, in which the decision to stop (and rest or change an activity) is determined by self-awareness of an exacerbation of symptoms, and time-contingent pacing, which is determined by a set schedule of activities that a patient estimates he or she is able to complete without triggering post-exertional malaise (PEM). Thus, the principle behind pacing for CFS is to avoid overexertion and an exacerbation of symptoms. It is not aimed at treating the illness as a whole. Those whose illness appears stable may gradually increase activity and exercise levels, but according to the principle of pacing, must rest or reduce their activity levels if it becomes clear that they have exceeded their limits.[100][20] Use of a heart-rate monitor with pacing to monitor and manage activity levels is recommended by a number of patient groups,[102] and the CDC considers it useful for some individuals to help avoid post-exertional malaise.[8]

Energy envelope theory

Energy envelope theory, considered to be consistent with pacing, is a management strategy suggested in the 2011 international consensus criteria for ME, which refers to using an "energy bank budget". Energy envelope theory was devised by psychologist Leonard Jason, who previously had CFS.[103] Energy envelope theory states that patients should stay within, and avoid pushing through, the envelope of energy available to them, so as to reduce the post-exertional malaise "payback" caused by overexertion. This may help them make "modest gains" in physical functioning.[104][105] Several studies have found energy envelope theory to be a helpful management strategy, noting that it reduces symptoms and may increase the level of functioning in CFS.[106][107][105] Energy envelope theory does not recommend unilaterally increasing or decreasing activity and is not intended as a therapy or cure for CFS.[106] It has been promoted by various patient groups.[108][109] Some patient groups recommend using a heart rate monitor to increase awareness of exertion and enable patients to stay within their aerobic threshold envelope.[110][111] Despite a number of studies showing positive results for energy envelope theory, randomized controlled trials are lacking.[citation needed]

Exercise

Stretching, movement therapies, and toning exercises are recommended for pain in patients with CFS. In many chronic illnesses, aerobic exercise is beneficial, but in chronic fatigue syndrome, the CDC does not recommend it. The CDC states:[8]

Any activity or exercise plan for people with ME/CFS needs to be carefully designed with input from each patient. While vigorous aerobic exercise can be beneficial for many chronic illnesses, patients with ME/CFS do not tolerate such exercise routines. Standard exercise recommendations for healthy people can be harmful for patients with ME/CFS. However, it is important that patients with ME/CFS undertake activities that they can tolerate...

Counseling

Chronic illness can impact mental health, and depression or anxiety resulting from ME/CFS is common.[41] Psychotherapy may help patients manage the stress of being ill, apply self-management strategies for their symptoms, and cope with physical pain. However, treating co-occurring anxiety or depression will not cure ME/CFS, and talk therapy should not be undertaken in an attempt to cure ME/CFS.[8][20]

Nutrition

A proper diet is a significant contributor to the health of any individual. Medical consultation about diet and supplements is recommended for persons with CFS.[8] Persons with CFS may benefit from a balanced diet and properly supervised administration of nutritional support if deficiencies are detected by medical testing. Risks of nutritional supplements include interactions with prescribed medications.[112][8]

Treatment

There are no approved treatments for ME/CFS. Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and graded exercise therapy (GET) have been proposed, but their safety and efficacy are disputed. The drug rintatolimod has been trialed and has been approved in Argentina.

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy for ME/CFS is a variant of CBT that assumes a cognitive-behavioral model of ME/CFS. In this model, people with ME/CFS mistakenly attribute their illness solely to physical causes, and their condition is perpetuated by a fear of triggering symptoms, which leads to a vicious cycle of deconditioning and avoidance of activity. CBT aims to help patients view unhelpful thoughts and behaviors as factors in their illness. This model has been criticized as lacking evidence and being at odds with the biological changes associated with ME/CFS, and the use of this type of CBT has been the subject of much controversy.[113][114][115]

NICE removed their recommendation for this form of CBT in 2021, replacing it with a recommendation to offer patient CBT for help coping with distress that illness causes. The guidelines emphasize that CBT for people with ME/CFS should not assume that unhelpful beliefs cause their illness, and should not be portrayed as curative.[91] Similarly, the CDC stopped recommending CBT as a treatment in 2017, recommending counseling as a coping method instead.[116][8]

A 2015 National Institutes of Health report concluded that while counseling and behavior therapies could produce benefits for some people, they may not yield improvement in quality of life, and because of this limitation such therapies should not be considered as a primary treatment, but rather should be used only as one component of a broader approach.[117] This same report stated that although counseling approaches have shown benefit in some measures of fatigue, function and overall improvement, these approaches have been inadequately studied in subgroups of the wider CFS patient population. Further concern was expressed that reporting of negative effects experienced by patients receiving counseling and behavior therapies had been poor.[118] A report by the Institute of Medicine published in 2015 states that it is unclear whether CBT helps to improve cognitive impairments experienced by patients.[2]:265

A 2014 systematic review reported that there was only limited evidence that patients increased levels of physical activity after receiving CBT. The authors concluded that, as this finding is contrary to the cognitive behavioural model of CFS, patients receiving CBT were adapting to the illness rather than recovering from it.[119] In a letter published online in the Lancet in 2016, Charles Shepherd, medical advisor to the ME Association, expressed the view that the contention between patients and researchers lay in "a flawed model of causation that takes no account of the heterogeneity of both clinical presentations and disease pathways that come under the umbrella diagnosis of ME/CFS".[120]

A 2020 systematic review did not find CBT to be effective. While most studies claimed positive results, overall evidence quality was low. The use of subjective outcomes in non-blinded trials rendered the results prone to bias, and adverse effects were not reported. When objective outcomes were used, improvements were not seen. Further, the reviewers concluded that the applicability of these studies to modern patient cohorts was dubious because all the studies analyzed used the older Oxford of Fukuda criteria, which did not require PEM.[121]

A 2022 evidence review contracted by the CDC found weak evidence supporting a small to moderate positive effect for CBT.[96](p23)

Patient organisations have rebuffed the use of CBT as a treatment for CFS to alter illness beliefs.[122][123] The ME Association recommended in 2015, based on the results of an opinion survey of 493 patients who had received CBT treatment in the UK, CBT in its current form should not be used as a primary intervention for people with CFS.[124] In 2019, a large UK survey of people with ME/CFS reported that CBT was ineffective for more than half of respondents.[125]

Graded exercise therapy

Graded exercise therapy (GET) is a programme of physical therapy that starts at a patient's baseline and gradually increases over time. Like CBT, it assumes that patients' fears of activity and deconditioning play a significant role, and its safety and efficacy are debated.[113][114][115]

The 2021 NICE guidelines removed GET as a recommended treatment due to low quality evidence regarding benefit, with the guidelines now telling clinicians not to prescribe "any programme that ... uses fixed incremental increases in physical activity or exercise, for example, graded exercise therapy." [20] The CDC withdrew their recommendation for GET in 2017.[116]

A 2022 review contracted by the CDC found that GET may produce small to medium improvements in fatigue, functioning, depression, anxiety, and sleep, based on weak evidence. The authors concluded that trials suffered from methodological limitations, had limited reporting of harms, and generally enrolled patients based on older definitions of ME/CFS that do not require PEM. The CDC does not recommend GET, and there is some evidence of harm.[115][96]

A 2019 updated Cochrane review stated that exercise therapy probably has a positive effect on fatigue in adults, and slightly improves sleep, but the long-term effects are unknown and relevance to current definitions of ME/CFS is limited.[126][9] Cochrane started re-evaluating the effects of exercise therapies in chronic fatigue syndrome in 2020.[9][127]

An independent re-analysis of the same studies as the Cochrane review concluded that GET is ineffective and there was no evidence of safety, citing the risk of bias in non-blinded trials with subjective outcome measures, the use of broad inclusion criteria, potential problems with the questionnaires used, and inconsistent dropout rates.[115]

A 2020 systematic review found that GET was not shown to be effective, due to the low quality and high risk of bias of trials. None of the studies analyzed used a definition of ME/CFS that required PEM, and few reported adverse effects. The main outcomes were self-reported and subjective, which may create bias when blinding is impossible.[114]

Patient organisations have long criticised the use of exercise therapy, most notably GET, as a treatment for ME/CFS.[123][113] Based on an opinion survey of patients who had received GET, in 2015 the ME Association concluded, GET in its current delivered form should not be recommended as a primary intervention for persons with ME/CFS.[124]

Adaptive pacing therapy

APT, not to be confused with pacing,[128] is a therapy rather than a management strategy.[129] APT is based on the idea that CFS involves a person only having a limited amount of available energy, and using this energy wisely will mean the "limited energy will increase gradually".[129]:5 A large clinical trial known as the PACE trial found APT was no more effective than usual care or specialized medical care.[130] The PACE trial generated much criticism due to the broad Oxford criteria patient selection, the standards of outcome effectiveness being lowered during the study, and re-analysis of the data not supporting the magnitude of improvements initially reported.[131]

Unlike pacing, APT is based on the cognitive behavioral model of chronic fatigue syndrome and involves increasing activity levels, which it states may temporarily increase symptoms.[132] In APT, the patient first establishes a baseline level of activity, which can be carried out consistently without any post-exertional malaise ("crashes"). APT states that persons should plan to increase their activity, as able. However, APT also requires patients to restrict their activity level to only 70% of what they feel able to do, while also warning against too much rest.[129] This has been described as contradictory, and Jason states that in comparison with pacing, this 70% limit restricts the activities that patients are capable of and results in a lower level of functioning.[128] Jason and Goudsmit, who first described pacing and the energy envelope theory for CFS, have both criticized APT for being inconsistent with the principles of pacing and highlighted significant differences.[128] APT was promoted by Action for ME until 2019. Action for ME was the patient charity involved in the PACE trial.[132]

Rintatolimod

Rintatolimod is a double-stranded RNA drug developed to modulate an antiviral immune reaction through activation of toll-like receptor 3. In several clinical trials of CFS, the treatment has shown a reduction in symptoms, but improvements were not sustained after discontinuation.[133] Evidence supporting the use of rintatolimod is deemed low to moderate.[21] The US FDA has denied commercial approval, called a new drug application, citing several deficiencies and gaps in safety data in the trials, and concluded that the available evidence is insufficient to demonstrate its safety or efficacy in CFS.[134][135] Rintatolimod has been approved for marketing and treatment for persons with CFS in Argentina ,[136] and in 2019, FDA regulatory requirements were met for exportation of rintatolimod to the country.[137]

Prognosis

Information on the prognosis of CFS is limited, and the course of the illness is variable.[138] According to the NICE guideline, CFS "varies in long-term outlook from person to person."[139] Complete recovery, partial improvement, and worsening are all possible.[138] Symptoms generally fluctuate over days, weeks, or longer periods, and some people may experience periods of remission.[139] Overall, "many will need to adapt to living with ME/CFS."[139] Some people who improve need to manage their activities in order to prevent relapse.[138] Children and teenagers are more likely to recover or improve than adults.[138][139]

A 2005 systematic review found that for untreated CFS, "the median full recovery rate was 5% (range 0–31%) and the median proportion of patients who improved during follow-up was 39.5% (range 8–63%)," and that 8 to 30% of patients were able to return to work. Age at onset, a longer duration of follow-up, less fatigue severity at baseline, and other factors were occasionally, but non consistently, related to outcome.[140] Another review found that children have a better prognosis than adults, with 54–94% having recovered by follow-up, compared to less than 10% of adults returning to pre-illness levels of functioning.[141]

Epidemiology

Reported prevalence rates vary widely depending on how CFS/ME is defined and diagnosed.[11] Based on the 1994 CDC diagnostic criteria, the global prevalence rate for CFS is 0.89%.[11] In comparison, estimates using the 1988 CDC "Holmes" criteria and 2003 Canadian criteria for ME produced an incidence rate of only 0.17%.[11] Between 836,000 and 2.5 million Americans have ME/CFS, but that 84-91% of these are undiagnosed,[2](p1) and over 250,000 people in England and Wales are estimated to be affected.[142] The worldwide prevalence is 17 and 24 million.[11]

Females are diagnosed about 1.5 to 2.0 times more often with CFS than males.[11] An estimated 0.5% of children have CFS, and more adolescents are affected with the illness than younger children.[2]:182[24]

The incidence rate according to age has two peaks, one at 10–19 and another at 30–39 years,[143][4] and the rate of prevalence is highest between ages 40 and 60.[37][144]

History

Myalgic encephalomyelitis

- From 1934 onwards, outbreaks of a previously unknown illness began to be recorded by doctors.[145][146] Initially considered to be occurrences of poliomyelitis, the illness was subsequently referred to as "epidemic neuromyasthenia".[146]

- In the 1950s, the term "benign myalgic encephalomyelitis" was used in relation to a comparable outbreak at the Royal Free Hospital in London.[147] The descriptions of each outbreak were varied, but included symptoms of malaise, tender lymph nodes, sore throat, pain, and signs of encephalomyelitis.[148] The cause of the condition was not identified, although it appeared to be infectious, and the term "benign myalgic encephalomyelitis" was chosen to reflect the lack of mortality, the severe muscular pains, symptoms suggesting damage to the nervous system, and to the presumed inflammatory nature of the disorder. Björn Sigurðsson disapproved of the name, stating that the illness is rarely benign, does not always cause muscle pain, and is possibly never encephalomyelitic.[145] The syndrome appeared in sporadic as well as epidemic cases.[149]

- In 1969, benign myalgic encephalomyelitis appeared as an entry to the International Classification of Diseases under Diseases of the nervous system.[150]

- In 1986, Ramsay published the first diagnostic criteria for ME, in which the condition was characterized by: 1) muscle fatiguability in which, even after minimal physical effort, three or more days elapse before full muscle power is restored; 2) extraordinary variability or fluctuation of symptoms, even in the course of one day; and 3) chronicity.[151]

- By 1988, the continued work of Ramsay had demonstrated that, although the disease rarely resulted in mortality, it was often severely disabling.[2]:28–29 Because of this, Ramsay proposed that the prefix "benign" be dropped.[147][152][153]

Chronic fatigue syndrome

- In the mid-1980s, two large outbreaks of an illness that resembled mononucleosis drew national attention in the United States. Located in Nevada and New York, the outbreaks involved an illness characterized by "chronic or recurrent debilitating fatigue, and various combinations of other symptoms, including a sore throat, lymph node pain and tenderness, headache, myalgia, and arthralgias". An initial link to the Epstein-Barr virus had the illness acquire the name "chronic Epstein-Barr virus syndrome".[2]:29[87]

- In 1987, the CDC convened a working group to reach a consensus on the clinical features of the illness. The working group concluded that CFS was not new, and that the many different names given to it previously reflected widely differing concepts of the illness's cause and epidemiology.[154] The CDC working group chose "chronic fatigue syndrome" as a more neutral and inclusive name for the illness, but noted that "myalgic encephalomyelitis" was widely accepted in other parts of the world.[87]

- In 1988, the first definition of CFS was published. Although the cause of the illness remained unknown, several attempts were made to update this definition, most notably in 1994.[86]

- The most widely referenced diagnostic criteria and definition of CFS for research and clinical purposes were published in 1994 by the CDC.[53]

- In 2006, the CDC commenced a national program to educate the American public and health-care professionals about CFS.[155]

Other medical terms

A range of both theorised and confirmed medical entities and naming conventions have appeared historically in the medical literature dealing with ME and CFS. These include:

- Epidemic neuromyasthenia was a term used for outbreaks with symptoms resembling poliomyelitis.[145][156]

- Iceland disease and Akureyri disease were synonymous terms used for an outbreak of fatigue symptoms in Iceland.[157]

- Low natural killer syndrome, a term used mainly in Japan, reflected research showing diminished in vitro activity of natural killer cells isolated from patients.[158][159]

- Neurasthenia had been proposed as a historical diagnosis that occupied a similar medical and cultural space to CFS.[160]

- Royal Free disease was named after the historically significant outbreak in 1955 at the Royal Free Hospital used as an informal synonym for "benign myalgic encephalomyelitis".[161]

- Tapanui flu was a term commonly used in New Zealand, deriving from the name of a town, Tapanui, where numerous people had the syndrome.[162]

Society and culture

Naming

Many names have been proposed for the illness. Currently, the most commonly used are "chronic fatigue syndrome", "myalgic encephalomyelitis", and the umbrella term "ME/CFS". Reaching consensus on a name is challenging because the cause and pathology remain unknown.[2]:29–30

The term "chronic fatigue syndrome" has been criticized by some patients as being both stigmatizing and trivializing, and which in turn prevents the illness from being seen as a serious health problem that deserves appropriate research.[163] While many patients prefer "myalgic encephalomyelitis", which they believe better reflects the medical nature of the illness,[151][164] there is resistance amongst some clinicians toward the use of "myalgic encephalomyelitis" on the grounds that the inflammation of the central nervous system (myelitis) implied by the term has not been demonstrated.[165][166]

A 2015 report from the Institute of Medicine recommended the illness be renamed "systemic exertion intolerance disease", (SEID), and suggested new diagnostic criteria, proposing post-exertional malaise (PEM), impaired function, and sleep problems are core symptoms of ME/CFS. Additionally, they described cognitive impairment and orthostatic intolerance as distinguishing symptoms from other fatiguing illnesses.[2][167][168]

Economic impact

Economic costs due to CFS are "significant."[32] A 2021 paper by Leonard Jason and Arthur Mirin estimated the impact in the US to be $36-51 billion per year, or $31,592 to $41,630 per person, considering both lost wages and healthcare costs.[169] The CDC estimated direct healthcare costs alone at $9-14 billion annually.[32] A 2017 estimate for the annual economic burden in the United Kingdom was £3.3 billion.[14]

Awareness day

12 May is designated as ME/CFS International Awareness Day.[170] The day is observed so that stakeholders have an occasion to improve the knowledge of "the public, policymakers, and health-care professionals about the symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of ME/CFS, as well as the need for a better understanding of this complex illness."[171] It was chosen because it is the birthday of Florence Nightingale, who had an illness appearing similar to ME/CFS or fibromyalgia.[170][172]

Doctor–patient relations

People with CFS face stigma in healthcare settings, and doctors may have trouble managing an illness that lacks a clear cause or treatment.[2](p30)[173] There has been much disagreement over proposed causes, diagnosis, and treatment of the illness.[174][175][176][177] Some doctors believe it is psychological.[2](p234)[178] Most patients are convinced their illness is physical instead, straining doctor-patient relationships.[173] Clinicians may be unfamiliar with CFS, as it is often not covered in medical school.[51][173] Due to this unfamiliarity, patients may go undiagnosed for years,[41](p2861)[2](p1) or be misdiagnosed with mental conditions.[51][41](p2871) A substantial portion of doctors are uncertain about how to diagnose or manage CFS.[178] In a 2006 survey of GPs in southwest England, 75% accepted it as a "recognisable clinical entity," but 48% did not feel confident in diagnosing it, and 41% in managing it.[179][178]

The NAM report refers to CFS as "stigmatized," and the majority of patients report negative healthcare experiences.[2](p30)[173] These patients may feel that their doctor inappropriately calls their illness psychological or doubts the severity of their symptoms.[173] They may also feel forced to prove that they are legitimately ill.[180] Some may be given outdated treatments that provoke symptoms or assume their illness is due to unhelpful thoughts and deconditioning.[2](p25)[41](p2871)[51] In a 2009 survey, only 35% of patients considered their physicians experienced with CFS and only 23% thought their doctors knew enough to treat it.[178]

Blood donation

In 2010, several national blood banks adopted measures to discourage or prohibit individuals diagnosed with CFS from donating blood, based on concern following the 2009 claim of a link[181] between CFS and a retrovirus which was subsequently shown to be unfounded. Organizations adopting these or similar measures included the Canadian Blood Services,[182] the New Zealand Blood Service,[183] the Australian Red Cross Blood Service[184] and the American Association of Blood Banks.[185] In November 2010, the UK National Blood Service permanently deferred ME/CFS patients from donating blood to prevent potential harm to the donor.[186] Donation policy in the UK now states, "The condition is relapsing by nature and donation may make symptoms worse, or provoke a relapse in an affected individual."[187]

Controversy

Much contention has arisen over the cause, pathophysiology,[188] nomenclature,[189] and diagnostic criteria of CFS.[174][175] Historically, many professionals within the medical community were unfamiliar with CFS, or did not recognize it as a real condition; nor did agreement exist on its prevalence or seriousness.[190][191][192] Some people with CFS reject any psychological component.[193]

In 1970, two British psychiatrists, McEvedy and Beard, reviewed the case notes of 15 outbreaks of benign myalgic encephalomyelitis and concluded that it was caused by mass hysteria on the part of patients, or altered medical perception of the attending physicians.[194] Their conclusions were based on previous studies that found many normal physical test results, a lack of a discernible cause, and a higher prevalence of the illness in females. Consequently, the authors recommended that the disease should be renamed "myalgia nervosa". This perspective was rejected in a series of case studies by Melvin Ramsay and other staff of the Royal Free Hospital, the center of a significant outbreak.[195] The psychological hypothesis posed by McEvedy and Beard created great controversy, and convinced a generation of health professionals in the UK that this could be a plausible explanation for the condition, resulting in neglect by many medical specialties.[165] The specialty that did take a major interest in the illness was psychiatry.[196]

Because of the controversy, sociologists hypothesized that stresses of modern living might be a cause of the illness, while some in the media used the term "Yuppie flu" and called it a disease of the middle class.[196] People with disabilities from CFS were often not believed and were accused of being malingerers.[196] The November 1990 issue of Newsweek ran a cover story on CFS, which although supportive of an organic cause of the illness, also featured the term 'yuppie flu', reflecting the stereotype that CFS mainly affected yuppies. The implication was that CFS is a form of burnout. The term 'yuppie flu' is considered offensive by both patients and clinicians.[197][198]

In 2009, the journal Science[181] published a study that identified the XMRV retrovirus in a population of people with CFS. Other studies failed to reproduce this finding,[199][200][201] and in 2011, the editor of Science formally retracted its XMRV paper[202] while the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences similarly retracted a 2010 paper which had appeared to support the finding of a connection between XMRV and CFS.[203]

Research funding

United Kingdom

The lack of research funding and the funding bias towards biopsychosocial studies and against biomedical studies has been highlighted a number of times by patient groups and a number of UK politicians.[204] A parliamentary inquiry by an ad hoc group of parliamentarians in the United Kingdom, set up and chaired by former MP, Dr Ian Gibson, called the Group on Scientific Research into CFS/ME,[205]:169–86[206] was addressed by a government minister claiming that few good biomedical research proposals have been submitted to the Medical Research Council (MRC) in contrast to those for psychosocial research. They were also told by other scientists of proposals that have been rejected, with claims of bias against biomedical research. The MRC confirmed to the group that from April 2003 to November 2006, it has turned down 10 biomedical applications relating to CFS/ME and funded five applications relating to CFS/ME, mostly in the psychiatric/psychosocial domain.[206]

In 2008, the MRC set up an expert group to consider how the MRC might encourage new high-quality research into CFS/ME and partnerships between researchers already working on CFS/ME and those in associated areas. It currently lists CFS/ME with a highlight notice, inviting researchers to develop high-quality research proposals for funding.[207] In February 2010, the All-Party Parliamentary Group on ME (APPG on ME) produced a legacy paper, which welcomed the recent MRC initiative, but felt that far too much emphasis in the past had been on psychological research, with insufficient attention to biomedical research, and that further biomedical research must be undertaken to help discover a cause and more effective forms of management for this disease.[208]

A 2016 report by ME Research looking at UK funding for ME/CFS between Jan 2006 and Dec 2015 found that 99 grants had been funded, totalling £49 million, with the largest number of studies being related to "Biological and endogenous factors".[209]

Controversy surrounds psychologically oriented models of the disease and behavioral treatments conducted in the UK.[210]

United States

In 1998, $13 million for CFS research was found to have been redirected or improperly accounted for by the United States CDC, and officials at the agency misled Congress about the irregularities. The agency stated that they needed the funds to respond to other public-health emergencies. The director of a US national patient advocacy group charged the CDC had a bias against studying the disease. The CDC pledged to improve their practices and to restore the $13 million to CFS research over three years.[211]

On 29 October 2015, the National Institutes of Health declared its intent to increase research on ME/CFS. The NIH Clinical Center was to study individuals with ME/CFS, and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke would lead the Trans-NIH ME/CFS Research Working Group as part of a multi-institute research effort.[212]

Notable cases

In 1989, The Golden Girls (1985–1992) featured chronic fatigue syndrome in a two-episode arc, "Sick and Tired: Part 1" and "Part 2", in which protagonist Dorothy Zbornak, portrayed by Bea Arthur, after a lengthy battle with her doctors in an effort to find a diagnosis for her symptoms, is finally diagnosed with CFS.[213] American author Ann Bannon had CFS.[214] Laura Hillenbrand, author of the popular book Seabiscuit, has struggled with CFS since age 19.[215][216]

Research

Current research into ME/CFS may lead to a better understanding of the disease's causes, biomarkers to aid in diagnosis, and treatments to relieve symptoms.[2](p10) The emergence of long COVID has sparked increased interest in ME/CFS, as the two conditions may share pathology, and a treatment for one may treat the other.[217]

Causes

Recent research suggests dysfunction in many biological processes. These changes may share a common cause, but the true relationship between them is currently unknown. Metabolic areas of interest include disruptions in amino acid metabolism, the TCA cycle, ATP synthesis, and potentially increased lipid metabolism. Other research has investigated immune dysregulation and its potential connections to mitochondrial dysfunction. Autoimmunity has been proposed as a cause, but evidence is scant. People with ME/CFS may have abnormal gut microbiota, which has been proposed to affect mitochondria or nervous system function.[218]

Several small studies have investigated the genetics of ME/CFS, but none of their findings have been replicated.[219] A larger study, DecodeME, is currently underway in the United Kingdom.[220]

Treatments

Various drugs have been or are being investigated for treating ME/CFS.[221]

The drug rintatolimod is currently in an experimental trial in the US to treat both ME/CFS and Long COVID.[222] Low-dose naltrexone is also being studied as of 2023.[223] Rituximab, a drug that depletes B cells, was studied and found to be ineffective.[218]

Biomarkers

Many biomarkers for ME/CFS have been proposed based on research findings. But due to the use of a number of case definitions in research, some of which are non-specific such as the Sharpe (“Oxford”) and Fukuda (“old CDC”) definitions, no biomarkers have been widely validated or broadly clinically implemented.[218] Proposed markers include electrical measurements of blood cells and a combination of immune cell death rate and function.[223]

Challenges

ME/CFS affects multiple bodily systems, varies widely in severity, and fluctuates over time, creating heterogeneity within patient groups and making it very difficult to identify a singular cause. This variation may also cause treatments that are effective for some patients to have no effect or a negative effect in others.[223] Dividing patients into subtypes may help manage this heterogeneity.[218]

The existence of multiple diagnostic criteria, and variations in how scientists apply them, complicate comparisons between studies.[2](p53)[218] Some definitions, like the Oxford and Fukuda criteria, may fail to distinguish between chronic fatigue in general and ME/CFS, which requires PEM in modern definitions.[218] Definitions also vary in which co-occurring conditions preclude a diagnosis of ME/CFS.[2](p52)

See also

- Unrest (2017 film)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) | CDC". 13 April 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 2.26 2.27 2.28 2.29 2.30 2.31 Committee on the Diagnostic Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome; Board on the Health of Select Populations; Institute of Medicine (10 February 2015). Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK274235/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK274235.pdf. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ↑ "Recommendations – Myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy)/chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and management – Guidance". NICE. 29 October 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng206/chapter/Recommendations#diagnosis.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Pediatric chronic fatigue syndrome: current perspectives". Pediatric Health, Medicine and Therapeutics 9: 27–33. 2017. doi:10.2147/PHMT.S126253. PMID 29722371.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "What is ME/CFS? | Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) | CDC". 12 July 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/about/index.html.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Possible Causes | Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) | CDC". 15 May 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/about/possible-causes.html.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 "Myalgic Encephalomyelitis – Adult & Paediatric: International Consensus Primer for Medical Practitioners". 2012. http://www.investinme.org/Documents/Guidelines/Myalgic%20Encephalomyelitis%20International%20Consensus%20Primer%20-2012-11-26.pdf.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 "Treatment of ME/CFS | Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) | CDC". 19 November 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/treatment/index.html.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "Publication of Cochrane Review: 'Exercise therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome'". 21 May 2020. https://www.cochrane.org/news/publication-cochrane-review-exercise-therapy-chronic-fatigue-syndrome. "It now places more emphasis on the limited applicability of the evidence to definitions of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) used in the included studies, the long-term effects of exercise on symptoms of fatigue, and acknowledges the limitations of the evidence about harms that may occur."

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Chronic fatigue syndrome: progress and possibilities". The Medical Journal of Australia 212 (9): 428–433. May 2020. doi:10.5694/mja2.50553. PMID 32248536.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 "Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME)". Journal of Translational Medicine 18 (1): 100. February 2020. doi:10.1186/s12967-020-02269-0. PMID 32093722.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 "Etiology and Pathophysiology | Presentation and Clinical Course | Healthcare Providers | Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) | CDC". Cdc.gov. 12 July 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/healthcare-providers/presentation-clinical-course/etiology-pathophysiology.html.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Information for Healthcare Providers | CDC". 13 April 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/healthcare-providers/index.html.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 "Genetic risk factors of ME/CFS: a critical review". Human Molecular Genetics 29 (R1): R117–R124. September 2020. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddaa169. PMID 32744306.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 "Symptoms of ME/CFS | Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) | CDC". 19 November 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/symptoms-diagnosis/symptoms.html.

- ↑ "Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) | CDC". 13 April 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/index.html.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Systematic Review of the Epidemiological Burden of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Across Europe: Current Evidence and EUROMENE Research Recommendations for Epidemiology". Journal of Clinical Medicine (MDPI AG) 9 (5): 1557. May 2020. doi:10.3390/jcm9051557. PMID 32455633.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Chronic fatigue syndrome: a review". The American Journal of Psychiatry 160 (2): 221–236. February 2003. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.221. PMID 12562565.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Severely Affected Patients – Clinical Care of Patients – Healthcare Providers – Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)". CDC. 19 November 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/healthcare-providers/clinical-care-patients-mecfs/severely-affected-patients.html.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 "Recommendations – Myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy)/chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and management – Guidance". NICE. 29 October 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng206/chapter/recommendations#managing-mecfs.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Treatment of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Systematic Review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop". Annals of Internal Medicine 162 (12): 841–850. June 2015. doi:10.7326/M15-0114. PMID 26075755.

- ↑ "Annex 1: Epidemiology of CFS/ME". UK Department of Health. 6 January 2012. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/Browsable/DH_4879305.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 "Epidemiology | Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) | CDC". 12 July 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/healthcare-providers/presentation-clinical-course/epidemiology.html.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 "ME/CFS in Children | Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) | CDC". 15 May 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/me-cfs-children/index.html. "ME/CFS is often thought of as a problem in adults, but children (both adolescents and younger children) can also get ME/CFS."

- ↑ "The Lonely, Isolating, and Alienating Implications of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome". Healthcare 8 (4): 413. October 2020. doi:10.3390/healthcare8040413. PMID 33092097.

- ↑ "Cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021 (3): CD001027. July 2008. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001027.pub2. PMID 18646067.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Treating the Most Disruptive Symptoms First and Preventing Worsening of Symptoms | CDC". 19 November 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/healthcare-providers/clinical-care-patients-mecfs/treating-most-disruptive-symptoms.html.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "In the mind or in the brain? Scientific evidence for central sensitisation in chronic fatigue syndrome". European Journal of Clinical Investigation 42 (2): 203–12. February 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2011.02575.x. PMID 21793823.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "CDC – Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) – Diagnosis". Cdc.gov. https://www.cdc.gov/cfs/diagnosis/index.html.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "A Natural History of Disease Framework for Improving the Prevention, Management, and Research on Post-viral Fatigue Syndrome and Other Forms of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome". Frontiers in Medicine 8: 688159. 2021. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.688159. PMID 35155455.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 "Presentation and Clinical Course of ME/CFS | Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) | CDC". 19 November 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/healthcare-providers/presentation-clinical-course/index.html.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 "Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Advancing Research and Clinical Education". 28 February 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/grand-rounds/pp/2016/20160216-chronic-fatigue.html.

- ↑ "Disability and chronic fatigue syndrome: a focus on function". Archives of Internal Medicine 164 (10): 1098–107. May 2004. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.10.1098. PMID 15159267.

- ↑ "Use of exercise for treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome". Sports Medicine 21 (1): 35–48. January 1996. doi:10.2165/00007256-199621010-00004. PMID 8771284.

- ↑ "Reduced complexity of activity patterns in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: a case control study". BioPsychoSocial Medicine 3 (1): 7. June 2009. doi:10.1186/1751-0759-3-7. PMID 19490619.

- ↑ "Chronic musculoskeletal pain in patients with the chronic fatigue syndrome: a systematic review". European Journal of Pain 11 (4): 377–86. May 2007. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.06.005. PMID 16843021.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 37.4 37.5 37.6 37.7 "CDC Grand Rounds: Chronic Fatigue Syndrome - Advancing Research and Clinical Education". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 65 (50–51): 1434–1438. December 2016. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm655051a4. PMID 28033311. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/pdfs/mm655051a4.pdf. Retrieved 5 January 2017. ""The highest prevalence of illness is in persons aged 40–50 years..."".

- ↑ "The Health-Related Quality of Life for Patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis / Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)". PLOS ONE 10 (7): e0132421. 2015-07-06. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0132421. PMID 26147503. Bibcode: 2015PLoSO..1032421F.

- ↑ "The neuropsychiatric and neuropsychological features of chronic fatigue syndrome: revisiting the enigma". Current Psychiatry Reports 15 (4): 353. April 2013. doi:10.1007/s11920-013-0353-8. PMID 23440559.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 "Cognitive Dysfunction in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: a Review of Recent Evidence". Current Rheumatology Reports (Springer Science and Business Media LLC) 18 (5): 24. May 2016. doi:10.1007/s11926-016-0577-9. PMID 27032787.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 41.4 41.5 41.6 41.7 "Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Essentials of Diagnosis and Management" (in English). Mayo Clinic Proceedings 96 (11): 2861–2878. November 2021. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.07.004. PMID 34454716.

- ↑ "Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome – Etiology and Pathophysiology". 10 July 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/healthcare-providers/presentation-clinical-course/etiology-pathophysiology.html.

- ↑ "Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS)" (in en). Department of Health, State Government of Victoria, Australia. 2022-07-07. http://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/chronic-fatigue-syndrome-cfs.

- ↑ "Chronic viral infections in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)". J Transl Med 16 (1): 268. October 2018. doi:10.1186/s12967-018-1644-y. PMID 30285773.

- ↑ "Mechanisms Explaining Muscle Fatigue and Muscle Pain in Patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): a Review of Recent Findings". Current Rheumatology Reports 19 (1): 1. January 2017. doi:10.1007/s11926-017-0628-x. PMID 28116577.

- ↑ "Chronic fatigue syndrome (Tapanui flu)". March 2020. https://www.southerncross.co.nz/group/medical-library/chronic-fatigue-syndrome-tapanui-flu.

- ↑ "A systematic review of chronic fatigue, its syndromes and ethnicity: prevalence, severity, co-morbidity and coping". International Journal of Epidemiology 38 (6): 1554–70. December 2009. doi:10.1093/ije/dyp147. PMID 19349479.

- ↑ "ME/CFS, case definition, and serological response to Epstein–Barr virus. A systematic literature review". Fatigue: Biomedicine, Health & Behavior 6 (4): 220–34. 16 August 2018. doi:10.1080/21641846.2018.1503125. "The levels of antibodies to EBV in ME/CFS patients differed from those in controls in 14 studies. The differences in EBV serology that were revealed, were almost exclusively signs that may indicate higher EBV activity in the patient group. The serological differences between patients and controls were seen in the two studies in which ME/CFS was defined using the Canadian criteria, in 5 of the 9 studies using the Holmes criteria, in 1 of the 2 studies using modified Holmes criteria, in 2 of the 6 studies using the Fukuda criteria, and in 4 of the 7 studies using less known criteria. The single study using the Oxford criteria showed no difference between cases and controls. Conclusions: There seems to be increased EBV activity in subset(s) of ME/CFS patients.".

- ↑ "The HPA axis and the genesis of chronic fatigue syndrome". Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism 15 (2): 55–59. March 2004. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2003.12.002. PMID 15036250.

- ↑ "CFS: A Review of Epidemiology and Natural History Studies". Bulletin of the IACFS/ME 17 (3): 88–106. 2009. PMID 21243091.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 "Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations". Nature Reviews. Microbiology 21 (3): 133–146. January 2023. doi:10.1038/s41579-022-00846-2. PMID 36639608.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 "Biopsychosocial risk factors of persistent fatigue after acute infection: A systematic review to inform interventions". Journal of Psychosomatic Research 99: 120–129. August 2017. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.06.013. PMID 28712416. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/411168/2/Figure_1_v2.pdf.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 "Case definitions for chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME): a systematic review". BMJ Open 4 (2): e003973. February 2014. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003973. PMID 24508851.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 54.3 "A systematic review of neurological impairments in myalgic encephalomyelitis/ chronic fatigue syndrome using neuroimaging techniques". PLOS ONE 15 (4): e0232475. 2020. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0232475. PMID 32353033. Bibcode: 2020PLoSO..1532475M.

- ↑ "ICD-11 – Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f569175314. "Diseases of the nervous system"

- ↑ "Myalgic Encephalomyelitis: Symptoms and Biomarkers". Current Neuropharmacology 13 (5): 701–34. 2 February 2017. doi:10.2174/1570159X13666150928105725. PMID 26411464. "Decreased frontal grey matter".

- ↑ "Sympathetic nervous system dysfunction in fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and interstitial cystitis: a review of case-control studies". Journal of Clinical Rheumatology 20 (3): 146–50. April 2014. doi:10.1097/RHU.0000000000000089. PMID 24662556.

- ↑ "Sleep abnormalities in chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: a review". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 8 (6): 719–28. December 2012. doi:10.5664/jcsm.2276. PMID 23243408.

- ↑ "Frontier studies on fatigue, autonomic nerve dysfunction, and sleep-rhythm disorder". The Journal of Physiological Sciences 65 (6): 483–98. November 2015. doi:10.1007/s12576-015-0399-y. PMID 26420687.

- ↑ "Malfunctioning of the autonomic nervous system in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: a systematic literature review". European Journal of Clinical Investigation 44 (5): 516–26. May 2014. doi:10.1111/eci.12256. PMID 24601948.

- ↑ "Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Advancing Research and Clinical Education". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 16 February 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/grand-rounds/pp/2016/20160216-presentation-chronic-fatigue-H.pdf.

- ↑ "Altered immune response to exercise in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: a systematic literature review". Exercise Immunology Review 20: 94–116. 2014. PMID 24974723.

- ↑ "Metabolism in chronic fatigue syndrome". Advances in Clinical Chemistry 66: 121–172. 2014. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-801401-1.00005-0. ISBN 978-0-12-801401-1. PMID 25344988.

- ↑ "A narrative review on the similarities and dissimilarities between myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and sickness behavior". BMC Medicine 11: 64. March 2013. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-11-64. PMID 23497361.

- ↑ "A systematic review of chronic fatigue syndrome: don't assume it's depression". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 10 (2): 120–128. 2008. doi:10.4088/pcc.v10n0206. PMID 18458765.

- ↑ "Immunological similarities between cancer and chronic fatigue syndrome: the common link to fatigue?". Anticancer Research 29 (11): 4717–4726. November 2009. PMID 20032425.

- ↑ "Neuroendocrine and immune contributors to fatigue". PM & R 2 (5): 338–46. May 2010. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.04.008. PMID 20656615.

- ↑ "Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Hypofunction in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME)/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) as a Consequence of Activated Immune-Inflammatory and Oxidative and Nitrosative Pathways". Molecular Neurobiology 54 (9): 6806–19. November 2017. doi:10.1007/s12035-016-0170-2. PMID 27766535.

- ↑ "Chronic fatigue syndrome: an update focusing on phenomenology and pathophysiology". Current Opinion in Psychiatry 19 (1): 67–73. January 2006. doi:10.1097/01.yco.0000194370.40062.b0. PMID 16612182.