Chemistry:Ocean chemistry

| Component | Concentration (mol/kg) |

|---|---|

| H2O | 53.6 |

| Cl− | 0.546 |

| Na+ | 0.469 |

| Mg2+ | 0.0528 |

| SO2−4 | 0.0282 |

| Ca2+ | 0.0103 |

| K+ | 0.0102 |

| CT | 0.00206 |

| Br− | 0.000844 |

| BT (total boron) | 0.000416 |

| Sr2+ | 0.000091 |

| F− | 0.000068 |

Ocean chemistry, also known as marine chemistry, is influenced by plate tectonics and seafloor spreading, turbidity currents, sediments, pH levels, atmospheric constituents, metamorphic activity, and ecology. The field of chemical oceanography studies the chemistry of marine environments including the influences of different variables. Marine life has adapted to the chemistries unique to earth's oceans, and marine ecosystems are sensitive to changes in ocean chemistry.

The impact of human activity on the chemistry of the earth's oceans has increased over time, with pollution from industry and various land-use practices significantly affecting the oceans. Moreover, increasing levels of carbon dioxide in the earth's atmosphere have led to ocean acidification, which has negative effects on marine ecosystems. The international community has agreed that restoring the chemistry of the oceans is a priority, and efforts toward this goal are tracked as part of Sustainable Development Goal 14.

History

Chemistry is though to have to come from the oceans, beginning around 4 billion years ago, when it was released by carbon into the atmosphere.

Marine chemistry on earth

Organic compounds in the oceans

Colored dissolved organic matter (CDOM) is estimated to range 20-70% of carbon content of the oceans, being higher near river outlets and lower in the open ocean.[2]

Marine life is largely similar in biochemistry to terrestrial organisms, except that they inhabit a saline environment. One consequence of their adaptation is that marine organisms are the most prolific source of halogenated organic compounds.[3]

Chemical ecology of extremophiles

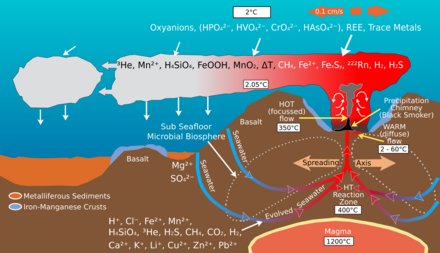

The ocean provides special marine environments inhabited by extremophiles that thrive under unusual conditions of temperature, pressure, and darkness. Such environments include hydrothermal vents and black smokers and cold seeps on the ocean floor, with entire ecosystems of organisms that have a symbiotic relationship with compounds that provided energy through a process called chemosynthesis.

Plate tectonics

Seafloor spreading on mid-ocean ridges is a global scale ion-exchange system.[4] Hydrothermal vents at spreading centers introduce various amounts of iron, sulfur, manganese, silicon and other elements into the ocean, some of which are recycled into the ocean crust. Helium-3, an isotope that accompanies volcanism from the mantle, is emitted by hydrothermal vents and can be detected in plumes within the ocean.[5]

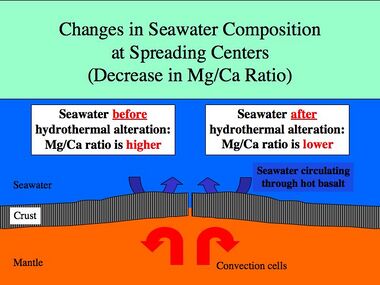

Spreading rates on mid-ocean ridges vary between 10 and 200 mm/yr. Rapid spreading rates cause increased basalt reactions with seawater. The magnesium/calcium ratio will be lower because more magnesium ions are being removed from seawater and consumed by the rock, and more calcium ions are being removed from the rock and released to seawater. Hydrothermal activity at ridge crest is efficient in removing magnesium.[6] A lower Mg/Ca ratio favors the precipitation of low-Mg calcite polymorphs of calcium carbonate (calcite seas).[4]

Slow spreading at mid-ocean ridges has the opposite effect and will result in a higher Mg/Ca ratio favoring the precipitation of aragonite and high-Mg calcite polymorphs of calcium carbonate (aragonite seas).[4]

Experiments show that most modern high-Mg calcite organisms would have been low-Mg calcite in past calcite seas,[7] meaning that the Mg/Ca ratio in an organism's skeleton varies with the Mg/Ca ratio of the seawater in which it was grown.

The mineralogy of reef-building and sediment-producing organisms is thus regulated by chemical reactions occurring along the mid-ocean ridge, the rate of which is controlled by the rate of sea-floor spreading.[6][7]

Human impacts

Marine pollution

Climate change

Increased carbon dioxide levels, resulting from anthropogenic factors or otherwise, have the potential to impact ocean chemistry. Global warming and changes in salinity have significant implications for ecology of marine environments.[8] One proposal suggests dumping massive amounts of lime, a base, to reverse the acidification and "increase the sea's ability to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere".[9][10][11]

Ocean acidification

Marine chemistry on other planets and their moons

A planetary scientist using data from the Cassini spacecraft has been researching the marine chemistry of Saturn's moon Enceladus using geochemical models to look at changes through time.[12] The presence of salts may indicate a liquid ocean within the moon, raising the possibility of the existence of life, "or at least for the chemical precursors for organic life".[12][13]

See also

References

- ↑ DOE (1994). "5". Handbook of methods for the analysis of the various parameters of the carbon dioxide system in sea water. ORNL/CDIAC-74. http://cdiac.esd.ornl.gov/ftp/cdiac74/chapter5.pdf.

- ↑ Coble, Paula G. (2007). "Marine Optical Biogeochemistry: The Chemistry of Ocean Color". Chemical Reviews 107 (2): 402–418. doi:10.1021/cr050350+. PMID 17256912.

- ↑ Gribble, Gordon W. (2004). "Natural Organohalogens: A New Frontier for Medicinal Agents?". Journal of Chemical Education 81 (10): 1441. doi:10.1021/ed081p1441. Bibcode: 2004JChEd..81.1441G.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Stanley, S.M.; Hardie, L.A. (1999). "Hypercalcification: paleontology links plate tectonics and geochemistry to sedimentology". GSA Today 9 (2): 1–7.

- ↑ Lupton, John (1998-07-15). "Hydrothermal helium plumes in the Pacific Ocean". Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 103 (C8): 15853–15868. doi:10.1029/98jc00146. ISSN 0148-0227. Bibcode: 1998JGR...10315853L.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Coggon, R. M.; Teagle, D. A. H.; Smith-Duque, C. E.; Alt, J. C.; Cooper, M. J. (2010-02-26). "Reconstructing Past Seawater Mg/Ca and Sr/Ca from Mid-Ocean Ridge Flank Calcium Carbonate Veins" (in en). Science 327 (5969): 1114–1117. doi:10.1126/science.1182252. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 20133522. Bibcode: 2010Sci...327.1114C.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Ries, Justin B. (2004). "Effect of ambient Mg/Ca ratio on Mg fractionation in calcareous marine invertebrates: A record of the oceanic Mg/Ca ratio over the Phanerozoic" (in en). Geology 32 (11): 981. doi:10.1130/G20851.1. ISSN 0091-7613. Bibcode: 2004Geo....32..981R.

- ↑ Millero, Frank J. (2007). "The Marine Inorganic Carbon Cycle". Chemical Reviews 107 (2): 308–341. doi:10.1021/cr0503557. PMID 17300138.

- ↑ Clark, Duncan (2009-07-12). "Cquestrate: adding lime to the oceans" (in en-GB). The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2009/jul/13/manchester-report-cquestrate.

- ↑ Katz, Ian (2009-07-12). "Twenty ideas that could save the world" (in en-GB). The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2009/jul/13/manchester-report-climate-change.

- ↑ http://www.infrastructurist.com/2009/07/14/from-the-uk-20-bold-schemes-that-could-save-us-from-global-warming/ July 14, 2009 Infrastructurist

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Pete Spotts Cassini spacecraft finds evidence for liquid water on Enceladus June 25, 2009 Christian Science Monitor

- ↑ Postberg, F.; Kempf, S.; Schmidt, J.; Brilliantov, N.; Beinsen, A.; Abel, B.; Buck, U.; Srama, R. (2009). "Sodium salts in E-ring ice grains from an ocean below the surface of Enceladus". Nature 459 (7250): 1098–1101. doi:10.1038/nature08046. PMID 19553992. Bibcode: 2009Natur.459.1098P.