List of animals featuring external asymmetry

This is a list of animals that markedly feature external asymmetry in some form. They are exceptions to the general pattern of symmetry in biology. In particular, these animals do not exhibit bilateral symmetry which permits streamlining and is common in animals.[1]

Birds

The crossbill has an unusual beak in which the upper and lower tips cross each other.[2]

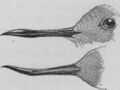

The wrybill is the only species of bird in the world with a beak that is bent sideways (always to the right).[2]

Many owl species, such as the barn owl, have asymmetrically positioned ears that enhance sound positioning.

Fish

Many flatfish, such as flounders, have eyes placed asymmetrically in the adult fish. The fish has the usual symmetrical body structure when it is young, but as it matures and moves to living close to the sea bed, the fish lies on its side, and the head twists so that both eyes are on the top.[4]

The jaws of the scale-eating cichlid Perissodus microlepis occur in two distinct morphological forms. One morph has its jaw twisted to the left, allowing it to eat scales more readily on its victim’s right flank. The other morph has its jaw twisted to the right, which makes it easier to eat scales on its victim’s left flank. The relative abundance of the two morphs in populations is regulated by frequency-dependent selection.[3][5][6]

Mammals

The narwhal has a helical tusk on its upper left jaw. Odobenocetops, an extinct toothed whale, may have possessed similar asymmetrical dentition, though it differed from the narwhal in possessing two erupted, rear-facing tusks with the right significantly longer than the left.

The sperm whale(Physeter macrocephalus) has a single nostril on its upper left head. The right nostril forms a phonic lip. The source of the air forced through the phonic lips is the right nasal passage. While the left nasal passage opens to the blow hole, the right nasal passage has evolved to supply air to the phonic lips. It is thought that the nostrils of the land-based ancestor of the sperm whale migrated through evolution to their current functions, the left nostril becoming the blowhole and the right nostril becoming the phonic lips.

The fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) has complex and asymmetrical coloration on its head.

Honey badgers of the subspecies signata have a second lower molar on the left side of their jaws, but not the right.[7]

Reptiles

Iwasaki's snail-eater snake (Pareas iwasakii) is a snail-eating specialist; even newly hatched individuals feed on snails. It has asymmetric jaws, which facilitates feeding on snails with dextral (clockwise coiled) shells. A consequence of this asymmetry is that this snake is much less adept at preying on sinistral (counterclockwise coiled) snails.

Non-avian dinosaurs

Stegosaurus stenops had two staggered rows of plates on its back, thus defying mirror symmetry.[8][9]

Invertebrates

Fiddler crabs and hermit crabs have one claw much larger than the other. If a male fiddler loses its large claw, it will grow another on the opposite side after moulting. A soft abdomen is also present in a hermit crab as an asymmetrical modification.

All gastropods are asymmetrical. This is easily seen in snails and sea snails, which have helical shells. At first glance slugs appear externally symmetrical, but their pneumostome (breathing hole) is always on the right side. The origin of asymmetry in gastropods is a subject of scientific debate.[10] Other gastropods develop external asymmetry, such as Glaucus atlanticus that develops asymmetrical cerata as they mature.

Histioteuthis is a genus of squid, commonly known as the cock-eyed squid, because in all species the right eye is normal-sized, round, blue and sunken; whereas the left eye is at least twice the diameter of the right eye, tubular, yellow-green, faces upward, and bulges out of the head.

Sessile animals such as sponges are asymmetrical.[1]

Corals build colonies that are not symmetrical, but the individual polyps exhibit radial symmetry.

Alpheidae feature asymmetrical claws that lack pincers, the larger of which can grow on either side of the body, and if lost can develop on the opposite arm instead.

Certain polyopisthocotylean monogeneans are asymmetrical, as an adaptation to their attachment to the gill of their fish hosts.

Certain parasitic copepods which live inside the gill chamber of their fish hosts are asymmetrical.

Gallery

Head of a male crossbill

Side and top view of a wrybill's beak

Chicoreus palmarosae, a sea snail

A red slug, clearly showing the pneumostome

Protocotyle euzetmaillardi, a polyopisthocotylean monogenean

Heteromicrocotyloides megaspinosus, a polyopisthocotylean monogenean

Silhouettes of bodies of 8 species of polyopisthocotylean monogeneans, all asymmetrical

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Symmetry, biological, cited at FactMonster.com from The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia (2007).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Ngutuparore, the wrybill. Narena Olliver, New Zealand Birds Limited. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Lee, H. J.; Kusche, H.; Meyer, A. (2012). "Handed Foraging Behavior in Scale-Eating Cichlid Fish: Its Potential Role in Shaping Morphological Asymmetry". PLoS ONE 7 (9): e44670. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044670. PMID 22970282. Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...744670L.

- ↑ American Plaice, Canadian Fisheries. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ↑ Hori, M. (1993). "Frequency-dependent natural selection in the handedness of scale-eating cichlid fish". Science 260: 216–219. doi:10.1126/science.260.5105.216. Bibcode: 1993Sci...260..216H. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/260/5105/216.

- ↑ Stewart, T. A.; Albertson, R. C. (2010). "Evolution of a unique predatory feeding apparatus: functional anatomy, development and a genetic locus for jaw laterality in Lake Tanganyika scale-eating cichlids". BMC Biology 8 (1): 8. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-8. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7007/8/8.

- ↑ Rosevear 1974, pp. 114–16

- ↑ Cameron, Robert P.; Cameron, John A.; Barnett, Stephen M. (2015-08-15). "Were there two forms of Stegosaurus?". arXiv:1508.03729 [q-bio.PE].

- ↑ Cameron, R. P.; Cameron, J. A.; Barnett, S. M. (2016-11-26). "Stegosaurus chirality". arXiv:1611.08760 [q-bio.PE].

- ↑ Louise R. Page (2006). "Modern insights on gastropod development: Reevaluation of the evolution of a novel body plan". Integrative and Comparative Biology 46 (2): 134–143. doi:10.1093/icb/icj018. PMID 21672730. Archived from the original on 12 April 2009. https://web.archive.org/web/20090412204751/http://intl-icb.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/46/2/134. Retrieved 8 February 2012.