Divergence of the sum of the reciprocals of the primes

The sum of the reciprocals of all prime numbers diverges; that is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{p\text{ prime}}\frac1p = \frac12 + \frac13 + \frac15 + \frac17 + \frac1{11} + \frac1{13} + \frac1{17} + \cdots = \infty }[/math]

This was proved by Leonhard Euler in 1737,[1] and strengthens (i.e. it gives more information than) Euclid's 3rd-century-BC result that there are infinitely many prime numbers.

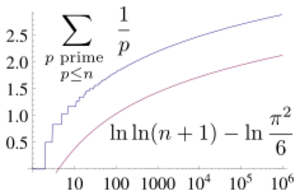

There are a variety of proofs of Euler's result, including a lower bound for the partial sums stating that

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{\scriptstyle p\text{ prime}\atop \scriptstyle p\le n}\frac1p \ge \ln \ln (n+1) - \ln\frac{\pi^2}6 }[/math]

for all natural numbers n. The double natural logarithm (ln ln) indicates that the divergence might be very slow, which is indeed the case. See Meissel–Mertens constant.

The harmonic series

First, we describe how Euler originally discovered the result. He was considering the harmonic series

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac{1}{n} = 1 + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{4} + \cdots = \infty }[/math]

He had already used the following "product formula" to show the existence of infinitely many primes.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac{1}{n} = \prod_{p} \left( 1+\frac{1}{p}+\frac{1}{p^2}+\cdots \right) = \prod_{p} \frac{1}{1-p^{-1}} }[/math]

Here the product is taken over the set of all primes.

Such infinite products are today called Euler products. The product above is a reflection of the fundamental theorem of arithmetic. Euler noted that if there were only a finite number of primes, then the product on the right would clearly converge, contradicting the divergence of the harmonic series.

Proofs

Euler's proof

Euler considered the above product formula and proceeded to make a sequence of audacious leaps of logic. First, he took the natural logarithm of each side, then he used the Taylor series expansion for ln x as well as the sum of a converging series:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \ln \left( \sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac{1}{n}\right) & {} = \ln\left( \prod_p \frac{1}{1-p^{-1}}\right) = -\sum_p \ln \left( 1-\frac{1}{p}\right) \\[5pt] & = \sum_p \left( \frac{1}{p} + \frac{1}{2p^2} + \frac{1}{3p^3} + \cdots \right) \\[5pt] & = \sum_{p}\frac{1}{p} + \frac{1}{2}\sum_p \frac{1}{p^2} + \frac{1}{3}\sum_p \frac{1}{p^3} + \frac{1}{4}\sum_p \frac{1}{p^4}+ \cdots \\[5pt] & = A + \frac{1}{2} B+ \frac{1}{3} C+ \frac{1}{4} D + \cdots \\[5pt] & = A + K \end{align} }[/math]

for a fixed constant K < 1. Then he invoked the relation

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{n=1}^\infty\frac1n=\ln\infty, }[/math]

which he explained, for instance in a later 1748 work,[2] by setting x = 1 in the Taylor series expansion

- [math]\displaystyle{ \ln\left(\frac1{1-x}\right)=\sum_{n=1}^\infty\frac{x^{n}}n. }[/math]

This allowed him to conclude that

- [math]\displaystyle{ A=\frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{5} + \frac{1}{7} + \frac{1}{11} + \cdots = \ln \ln \infty. }[/math]

It is almost certain that Euler meant that the sum of the reciprocals of the primes less than n is asymptotic to ln ln n as n approaches infinity. It turns out this is indeed the case, and a more precise version of this fact was rigorously proved by Franz Mertens in 1874.[3] Thus Euler obtained a correct result by questionable means.

Erdős's proof by upper and lower estimates

The following proof by contradiction is due to Paul Erdős.

Let pi denote the ith prime number. Assume that the sum of the reciprocals of the primes converges; i.e.,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{i=1}^\infty \frac 1 {p_i} \lt \infty }[/math]

Then there exists a smallest positive integer k such that

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{i=k+1}^\infty \frac 1 {p_i} \lt \frac12 \qquad(1) }[/math]

For a positive integer x, let Mx denote the set of those n in {1, 2, …, x} which are not divisible by any prime greater than pk (or equivalently all n ≤ x which are a product of powers of primes pi ≤ pk). We will now derive an upper and a lower estimate for |Mx|, the number of elements in Mx. For large x, these bounds will turn out to be contradictory.

Upper estimate:

- Every n in Mx can be written as n = m2r with positive integers m and r, where r is square-free. Since only the k primes p1, …, pk can show up (with exponent 1) in the prime factorization of r, there are at most 2k different possibilities for r. Furthermore, there are at most √x possible values for m. This gives us the upper estimate

- [math]\displaystyle{ |M_x| \le 2^k\sqrt{x} \qquad(2) }[/math]

Lower estimate:

- The remaining x − |Mx| numbers in the set difference {1, 2, …, x} \ Mx are all divisible by a prime greater than pk. Let Ni,x denote the set of those n in {1, 2, …, x} which are divisible by the ith prime pi. Then

- [math]\displaystyle{ \{1,2,\ldots,x\}\smallsetminus M_x = \bigcup_{i=k+1}^\infty N_{i,x} }[/math]

- Since the number of integers in Ni,x is at most x/pi (actually zero for pi > x), we get

- [math]\displaystyle{ x-|M_x| \le \sum_{i=k+1}^\infty |N_{i,x}|\lt \sum_{i=k+1}^\infty \frac x {p_i} }[/math]

- Using (1), this implies

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac x 2 \lt |M_x| \qquad(3) }[/math]

This produces a contradiction: when x ≥ 22k + 2, the estimates (2) and (3) cannot both hold, because x/2 ≥ 2k√x.

Proof that the series exhibits log-log growth

Here is another proof that actually gives a lower estimate for the partial sums; in particular, it shows that these sums grow at least as fast as ln ln n. The proof is an adaptation of the product expansion idea of Euler. In the following, a sum or product taken over p always represents a sum or product taken over a specified set of primes.

The proof rests upon the following four inequalities:

- Every positive integer i can be uniquely expressed as the product of a square-free integer and a square. This gives the inequality

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{i=1}^n \frac 1 i \le \prod_{p \le n} \left(1 + \frac 1 p \right) \sum_{k=1}^n \frac 1 {k^2} }[/math]

- where for every i between 1 and n the (expanded) product corresponds to the square-free part of i and the sum corresponds to the square part of i (see fundamental theorem of arithmetic).

- The upper estimate for the natural logarithm

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \ln(n+1) &= \int_1^{n+1} \frac{dx}x \\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n\underbrace{\int_i^{i+1}\frac{dx}x}_{{} \,\lt \, \frac1i} \\ &\lt \sum_{i=1}^n \frac 1 i \end{align} }[/math]

- The lower estimate 1 + x < exp(x) for the exponential function, which holds for all x > 0.

- Let n ≥ 2. The upper bound (using a telescoping sum) for the partial sums (convergence is all we really need)

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \sum_{k=1}^n \frac 1 {k^2} &\lt 1 + \sum_{k=2}^n \underbrace{\left(\frac1{k - \frac{1}{2}} - \frac1{k + \frac{1}{2}}\right)}_{=\, \frac{1}{k^2 - \frac14} \,\gt \, \frac{1}{k^2}} \\ &= 1 + \frac23 - \frac1{n + \frac{1}{2}} \lt \frac53 \end{align} }[/math]

Combining all these inequalities, we see that

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \ln(n+1) & \lt \sum_{i=1}^n\frac{1}{i} \\ & \le \prod_{p \le n} \left(1 + \frac{1}{p}\right) \sum_{k=1}^n \frac{1}{k^2} \\ & \lt \frac53\prod_{p \le n} \exp\left(\frac{1}{p}\right) \\ & = \frac53\exp\left(\sum_{p \le n} \frac{1}{p} \right) \end{align} }[/math]

Dividing through by 5/3 and taking the natural logarithm of both sides gives

- [math]\displaystyle{ \ln\ln(n + 1) - \ln\frac53 \lt \sum_{p \le n} \frac{1}{p} }[/math]

as desired. ∎

Using

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{1}{k^2} = \frac{\pi^2}6 }[/math]

(see the Basel problem), the above constant ln 5/3 = 0.51082… can be improved to ln π2/6 = 0.4977…; in fact it turns out that

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lim_{n \to \infty } \left( \sum_{p \leq n} \frac{1}{p} - \ln \ln n \right) = M }[/math]

where M = 0.261497… is the Meissel–Mertens constant (somewhat analogous to the much more famous Euler–Mascheroni constant).

Proof from Dusart's inequality

From Dusart's inequality, we get

- [math]\displaystyle{ p_n \lt n \ln n + n \ln \ln n \quad\mbox{for } n \ge 6 }[/math]

Then

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac1{ p_n} &\ge \sum_{n=6}^\infty \frac1{ p_n} \\ &\ge \sum_{n=6}^\infty \frac1{ n \ln n + n \ln \ln n} \\ &\ge \sum_{n=6}^\infty \frac1{2n \ln n} = \infty \end{align} }[/math]

by the integral test for convergence. This shows that the series on the left diverges.

Partial sums

While the partial sums of the reciprocals of the primes eventually exceed any integer value, they never equal an integer.

One proof[4] is by induction: The first partial sum is 1/2, which has the form odd/even. If the nth partial sum (for n ≥ 1) has the form odd/even, then the (n + 1)st sum is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac\text{odd}\text{even} + \frac{1}{p_{n+1}} = \frac{\text{odd} \cdot p_{n+1} + \text{even}}{\text{even} \cdot p_{n+1}} = \frac{\text{odd} + \text{even}}\text{even} = \frac\text{odd}\text{even} }[/math]

as the (n + 1)st prime pn + 1 is odd; since this sum also has an odd/even form, this partial sum cannot be an integer (because 2 divides the denominator but not the numerator), and the induction continues.

Another proof rewrites the expression for the sum of the first n reciprocals of primes (or indeed the sum of the reciprocals of any set of primes) in terms of the least common denominator, which is the product of all these primes. Then each of these primes divides all but one of the numerator terms and hence does not divide the numerator itself; but each prime does divide the denominator. Thus the expression is irreducible and is non-integer.

See also

- Euclid's theorem that there are infinitely many primes

- Small set (combinatorics)

- Brun's theorem, on the convergent sum of reciprocals of the twin primes

- List of sums of reciprocals

References

- ↑ Euler, Leonhard (1737). "Variae observationes circa series infinitas". Commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Petropolitanae 9: 160–188.

- ↑ Euler, Leonhard (1748). Introductio in analysin infinitorum. Tomus Primus. Lausanne: Bousquet. p. 228, ex. 1.

- ↑ Mertens, F. (1874). "Ein Beitrag zur analytischer Zahlentheorie". J. Reine Angew. Math. 78: 46–62.

- ↑ Lord, Nick (2015). "Quick proofs that certain sums of fractions are not integers". The Mathematical Gazette 99: 128–130. doi:10.1017/mag.2014.16.

- Sources

- Dunham, William (1999). Euler The Master of Us All. MAA. pp. 61–79. ISBN 0-88385-328-0.

External links

- Divergence of the sum of the reciprocals of the primes (Original source)

- Caldwell, Chris K.. "There are infinitely many primes, but, how big of an infinity?". http://www.utm.edu/research/primes/infinity.shtml.