Datalog

| Paradigm | Logic, Declarative |

|---|---|

| Family | Prolog |

| First appeared | 1977 |

| Typing discipline | Weak |

| Dialects | |

| Datomic, .QL, Soufflé, XTDB, etc. | |

| Influenced by | |

| Prolog | |

Datalog is a declarative logic programming language. While it is syntactically a subset of Prolog, Datalog generally uses a bottom-up rather than top-down evaluation model. This difference yields significantly different behavior and properties from Prolog. It is often used as a query language for deductive databases. Datalog has been applied to problems in data integration, networking, program analysis, and more.

Example

A Datalog program consists of facts, which are statements that are held to be true, and rules, which say how to deduce new facts from known facts. For example, here are two facts that mean xerces is a parent of brooke and brooke is a parent of damocles:

parent(xerces, brooke). parent(brooke, damocles).

The names are written in lowercase because strings beginning with an uppercase letter stand for variables. Here are two rules:

ancestor(X, Y) :- parent(X, Y). ancestor(X, Y) :- parent(X, Z), ancestor(Z, Y).

The :- symbol is read as "if", and the comma is read "and", so these rules mean:

- X is an ancestor of Y if X is a parent of Y.

- X is an ancestor of Y if X is a parent of some Z, and Z is an ancestor of Y.

The meaning of a program is defined to be the set of all of the facts that can be deduced using the initial facts and the rules. This program's meaning is given by the following facts:

parent(xerces, brooke). parent(brooke, damocles). ancestor(xerces, brooke). ancestor(brooke, damocles). ancestor(xerces, damocles).

Some Datalog implementations don't deduce all possible facts, but instead answer queries:

?- ancestor(xerces, X).

This query asks: Who are all the X that xerces is an ancestor of? For this example, it would return brooke and damocles.

Comparison to relational databases

The non-recursive subset of Datalog is closely related to query languages for relational databases, such as SQL. The following table maps between Datalog, relational algebra, and SQL concepts:

| Datalog | Relational algebra | SQL |

|---|---|---|

| Relation | Relation | Table |

| Fact | Tuple | Row |

| Rule | n/a | Materialized view |

| Query | Select | Query |

More formally, non-recursive Datalog corresponds precisely to unions of conjunctive queries, or equivalently, negation-free relational algebra.

Schematic translation from non-recursive Datalog into SQL

|

|---|

s(x, y). t(y). r(A, B) :- s(A, B), t(B). CREATE TABLE s (

z0 TEXT NONNULL,

z1 TEXT NONNULL,

PRIMARY KEY (z0, z1)

);

CREATE TABLE t (

z0 TEXT NONNULL PRIMARY KEY

);

INSERT INTO s VALUES ('x', 'y');

INSERT INTO t VALUES ('y');

CREATE VIEW r AS

SELECT s.z0, s.z1

FROM s, t

WHERE s.z1 = t.z0;

|

Syntax

A Datalog program consists of a list of rules (Horn clauses).[1] If constant and variable are two countable sets of constants and variables respectively and relation is a countable set of predicate symbols, then the following BNF grammar expresses the structure of a Datalog program:

<program> ::= <rule> <program> | ""

<rule> ::= <atom> ":-" <atom-list> "."

<atom> ::= <relation> "(" <term-list> ")"

<atom-list> ::= <atom> | <atom> "," <atom-list> | ""

<term> ::= <constant> | <variable>

<term-list> ::= <term> | <term> "," <term-list> | ""

Atoms are also referred to as Template:Dfni. The atom to the left of the :- symbol is called the Template:Dfni of the rule; the atoms to the right are the Template:Dfni. Every Datalog program must satisfy the condition that every variable that appears in the head of a rule also appears in the body (this condition is sometimes called the Template:Dfni).[1][2]

There are two common conventions for variable names: capitalizing variables, or prefixing them with a question mark ?.[3]

Note that under this definition, Datalog does not include negation nor aggregates; see § Extensions for more information about those constructs.

Rules with empty bodies are called Template:Dfni. For example, the following rule is a fact:

r(x) :- .

The set of facts is called the Template:Dfni or Template:Dfni of the Datalog program. The set of tuples computed by evaluating the Datalog program is called the Template:Dfni or Template:Dfni.

Syntactic sugar

Many implementations of logic programming extend the above grammar to allow writing facts without the :-, like so:

r(x).

Some also allow writing 0-ary relations without parentheses, like so:

p :- q.

These are merely abbreviations (syntactic sugar); they have no impact on the semantics of the program.

Semantics

| Herbrand universe, base, and model of a Datalog program |

|---|

|

Program: edge(x, y). edge(y, z). path(A, B) :- edge(A, B). path(A, C) :- path(A, B), edge(B, C). |

Herbrand universe: x, y, z |

Herbrand base: edge(x, x), edge(x, y), ..., edge(z, z), path(x, x), ..., path(z, z) |

Herbrand model: edge(x, y), edge(y, z), path(x, y), path(y, z), path(x, z) |

There are three widely-used approaches to the semantics of Datalog programs: model-theoretic, fixed-point, and proof-theoretic. These three approaches can be proven equivalent.[4]

An atom is called Template:Dfni if none of its subterms are variables. Intuitively, each of the semantics define the meaning of a program to be the set of all ground atoms that can be deduced from the rules of the program, starting from the facts.

Model theoretic

A rule is called ground if all of its atoms (head and body) are ground. A ground rule R1 is a ground instance of another rule R2 if R1 is the result of a substitution of constants for all the variables in R2. The Herbrand base of a Datalog program is the set of all ground atoms that can be made with the constants appearing in the program. The Template:Dfni of a Datalog program is the smallest subset of the Herbrand base such that, for each ground instance of each rule in the program, if the atoms in the body of the rule are in the set, then so is the head.[5] The model-theoretic semantics define the minimal Herbrand model to be the meaning of the program.

Fixed-point

Let I be the power set of the Herbrand base of a program P. The immediate consequence operator for P is a map T from I to I that adds all of the new ground atoms that can be derived from the rules of the program in a single step. The least-fixed-point semantics define the least fixed point of T to be the meaning of the program; this coincides with the minimal Herbrand model.[6]

The fixpoint semantics suggest an algorithm for computing the minimal model: Start with the set of ground facts in the program, then repeatedly add consequences of the rules until a fixpoint is reached. This algorithm is called naïve evaluation.

Proof-theoretic

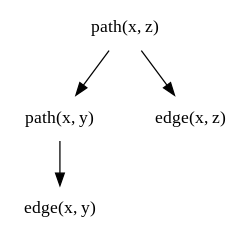

The proof-theoretic semantics defines the meaning of a Datalog program to be the set of facts with corresponding proof trees. Intuitively, a proof tree shows how to derive a fact from the facts and rules of a program.

One might be interested in knowing whether or not a particular ground atom appears in the minimal Herbrand model of a Datalog program, perhaps without caring much about the rest of the model. A top-down reading of the proof trees described above suggests an algorithm for computing the results of such queries. This reading informs the SLD resolution algorithm, which forms the basis for the evaluation of Prolog.

Evaluation

There are many different ways to evaluate a Datalog program, with different performance characteristics.

Bottom-up evaluation strategies

Bottom-up evaluation strategies start with the facts in the program and repeatedly apply the rules until either some goal or query is established, or until the complete minimal model of the program is produced.

Naïve evaluation

Naïve evaluation mirrors the fixpoint semantics for Datalog programs. Naïve evaluation uses a set of "known facts", which is initialized to the facts in the program. It proceeds by repeatedly enumerating all ground instances of each rule in the program. If each atom in the body of the ground instance is in the set of known facts, then the head atom is added to the set of known facts. This process is repeated until a fixed point is reached, and no more facts may be deduced. Naïve evaluation produces the entire minimal model of the program.[7]

Semi-naïve evaluation

Semi-naïve evaluation is a bottom-up evaluation strategy that can be asymptotically faster than naïve evaluation.[8]

Performance considerations

Naïve and semi-naïve evaluation both evaluate recursive Datalog rules by repeatedly applying them to a set of known facts until a fixed point is reached. In each iteration, rules are only run for "one step", i.e., non-recursively. As mentioned above, each non-recursive Datalog rule corresponds precisely to a conjunctive query. Therefore, many of the techniques from database theory used to speed up conjunctive queries are applicable to bottom-up evaluation of Datalog, such as

- Index selection[10]

- Query optimization, especially join order[11][12]

- Join algorithms

- Selection of data structures used to store relations; common choices include hash tables and B-trees, other possibilities include disjoint set data structures (for storing equivalence relations),[13] bries (a variant of tries),[14] binary decision diagrams,[15] and even SMT formulas[16]

Many such techniques are implemented in modern bottom-up Datalog engines such as Soufflé. Some Datalog engines integrate SQL databases directly.[17]

Bottom-up evaluation of Datalog is also amenable to parallelization. Parallel Datalog engines are generally divided into two paradigms:

- In the shared-memory, multi-core setting, Datalog engines execute on a single node. Coordination between threads may be achieved using locking or lock-free data structures. The shared-memory setting may be further divided into single instruction, multiple data and multiple instruction, multiple data paradigms:

- Datalog engines that execute on graphics processing units fall into the SIMD paradigm.[18]

- Datalog engines using OpenMP[19] are instances of the MIMD paradigm.

- In the shared-nothing setting, Datalog engines execute on a cluster of nodes. Such engines generally operate by splitting relations into disjoint subsets based on a hash function, performing computations (joins) on each node, and then exchanging newly-generated tuples over the network.[20] Examples include Datalog engines based on MPI,[9] Hadoop,[21] and Spark.[22]

Top-down evaluation strategies

SLD resolution is sound and complete for Datalog programs.

Magic sets

Top-down evaluation strategies begin with a query or goal. Bottom-up evaluation strategies can answer queries by computing the entire minimal model and matching the query against it, but this can be inefficient if the answer only depends on a small subset of the entire model. The magic sets algorithm takes a Datalog program and a query, and produces a more efficient program that computes the same answer to the query while still using bottom-up evaluation.[23] A variant of the magic sets algorithm has been shown to produce programs that, when evaluated using semi-naïve evaluation, are as efficient as top-down evaluation.[24]

Complexity

The decision problem formulation of Datalog evaluation is as follows: Given a Datalog program P split into a set of facts (EDB) E and a set of rules R, and a ground atom A, is A in the minimal model of P? In this formulation, there are three variations of the computational complexity of evaluating Datalog programs:[25]

- The Template:Dfni is the complexity of the decision problem when A and E are inputs and R is fixed.

- The Template:Dfni is the complexity of the decision problem when A and R are inputs and E is fixed.

- The Template:Dfni is the complexity of the decision problem when A, E, and R are inputs.

With respect to data complexity, the decision problem for Datalog is P-complete. With respect to program complexity, the decision problem is EXPTIME-complete. In particular, evaluating Datalog programs always terminates; Datalog is not Turing-complete.

Some extensions to Datalog do not preserve these complexity bounds. Extensions implemented in some Datalog engines, such as algebraic data types, can even make the resulting language Turing-complete.

Extensions

Several extensions have been made to Datalog, e.g., to support negation, aggregate functions, inequalities, to allow object-oriented programming, or to allow disjunctions as heads of clauses. These extensions have significant impacts on the language's semantics and on the implementation of a corresponding interpreter.

Datalog is a syntactic subset of Prolog, disjunctive Datalog, answer set programming, DatalogZ, and constraint logic programming. When evaluated as an answer set program, a Datalog program yields a single answer set, which is exactly its minimal model.[26]

Many implementations of Datalog extend Datalog with additional features; see § Datalog engines for more information.

Aggregation

Datalog can be extended to support aggregate functions.[27]

Notable Datalog engines that implement aggregation include:

Negation

Adding negation to Datalog complicates its semantics, leading to whole new languages and strategies for evaluation. For example, the language that results from adding negation with the stable model semantics is exactly answer set programming.

Stratified negation can be added to Datalog while retaining its model-theoretic and fixed-point semantics. Notable Datalog engines that implement stratified negation include:

Comparison to Prolog

Unlike in Prolog, statements of a Datalog program can be stated in any order. Datalog does not have Prolog's cut operator. This makes Datalog a fully declarative language.

In contrast to Prolog, Datalog

- disallows complex terms as arguments of predicates, e.g.,

p(x, y)is admissible but notp(f(x), y), - disallows negation,

- requires that every variable that appears in the head of a clause also appear in a literal in the body of the clause.

This article deals primarily with Datalog without negation (see also Syntax and semantics of logic programming § Extending Datalog with negation). However, stratified negation is a common addition to Datalog; the following list contrasts Prolog with Datalog with stratified negation. Datalog with stratified negation

- also disallows complex terms as arguments of predicates,

- requires that every variable that appears in the head of a clause also appear in a positive (i.e., not negated) atom in the body of the clause,

- requires that every variable appearing in a negative literal in the body of a clause also appear in some positive literal in the body of the clause.[30][unreliable source?]

Expressiveness

Datalog generalizes many other query languages. For instance, conjunctive queries and union of conjunctive queries can be expressed in Datalog. Datalog can also express regular path queries.

The Template:Dfni for Datalog asks, given a Datalog program, whether it is Template:Dfni, i.e., the maximal recursion depth reached when evaluating the program on an input database can be bounded by some constant. In other words, this question asks whether the Datalog program could be rewritten as a nonrecursive Datalog program, or, equivalently, as a union of conjunctive queries. Solving the boundedness problem on arbitrary Datalog programs is undecidable,[31] but it can be made decidable by restricting to some fragments of Datalog.

Datalog engines

Systems that implement languages inspired by Datalog, whether compilers, interpreters, libraries, or embedded DSLs, are referred to as Template:Dfni. Datalog engines often implement extensions of Datalog, extending it with additional data types, foreign function interfaces, or support for user-defined lattices. Such extensions may allow for writing non-terminating or otherwise ill-defined programs.[citation needed]

Uses and influence

Datalog is quite limited in its expressivity. It is not Turing-complete, and doesn't include basic data types such as integers or strings. This parsimony is appealing from a theoretical standpoint, but it means Datalog per se is rarely used as a programming language or knowledge representation language.[32] Most Datalog engines implement substantial extensions of Datalog. However, Datalog has a strong influence on such implementations, and many authors don't bother to distinguish them from Datalog as presented in this article. Accordingly, the applications discussed in this section include applications of realistic implementations of Datalog-based languages.

Datalog has been applied to problems in data integration, information extraction, networking, security, cloud computing and machine learning.[33][34] Google has developed an extension to Datalog for big data processing.[35]

Datalog has seen application in static program analysis.[36] The Soufflé dialect has been used to write pointer analyses for Java and a control-flow analysis for Scheme.[37][38] Datalog has been integrated with SMT solvers to make it easier to write certain static analyses.[39] The Flix dialect is also suited to writing static program analyses.[40]

Some widely used database systems include ideas and algorithms developed for Datalog. For example, the 1999 standard includes recursive queries, and the Magic Sets algorithm (initially developed for the faster evaluation of Datalog queries) is implemented in IBM's DB2.[41]

History

The origins of Datalog date back to the beginning of logic programming, but it became prominent as a separate area around 1977 when Hervé Gallaire and Jack Minker organized a workshop on logic and databases.[42] David Maier is credited with coining the term Datalog.[43]

See also

- Answer set programming

- Conjunctive query

- DatalogZ

- Disjunctive Datalog

- Flix

- SWRL

- Tuple-generating dependency (TGD), a language for integrity constraints on relational databases with a similar syntax to Datalog

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Ceri, Gottlob & Tanca 1989, p. 146.

- ↑ Eisner, Jason; Filardo, Nathaniel W. (2011). "Dyna: Extending Datalog for Modern AI". in de Moor, Oege; Gottlob, Georg; Furche, Tim et al. (in en). Datalog Reloaded. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 6702. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 181–220. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-24206-9_11. ISBN 978-3-642-24206-9. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-24206-9_11.

- ↑ Maier, David; Tekle, K. Tuncay; Kifer, Michael; Warren, David S. (2018-09-01), "Datalog: concepts, history, and outlook", Declarative Logic Programming: Theory, Systems, and Applications (Association for Computing Machinery and Morgan & Claypool) 20: pp. 3–100, doi:10.1145/3191315.3191317, ISBN 978-1-970001-99-0, https://doi.org/10.1145/3191315.3191317, retrieved 2023-03-02

- ↑ Van Emden, M. H.; Kowalski, R. A. (1976-10-01). "The Semantics of Predicate Logic as a Programming Language". Journal of the ACM 23 (4): 733–742. doi:10.1145/321978.321991. ISSN 0004-5411. https://doi.org/10.1145/321978.321991.

- ↑ Ceri, Gottlob & Tanca 1989, p. 149.

- ↑ Ceri, Gottlob & Tanca 1989, p. 150.

- ↑ Ceri, Gottlob & Tanca 1989, p. 154.

- ↑ Alvarez-Picallo, Mario; Eyers-Taylor, Alex; Peyton Jones, Michael; Ong, C.-H. Luke (2019). "Fixing Incremental Computation: Derivatives of Fixpoints, and the Recursive Semantics of Datalog". in Caires, Luís (in en). Programming Languages and Systems. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 11423. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 525–552. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-17184-1_19. ISBN 978-3-030-17184-1. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-17184-1_19.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Gilray, Thomas; Sahebolamri, Arash; Kumar, Sidharth; Micinski, Kristopher (2022-11-21). "Higher-Order, Data-Parallel Structured Deduction". arXiv:2211.11573 [cs.PL].

- ↑ Subotić, Pavle; Jordan, Herbert; Chang, Lijun; Fekete, Alan; Scholz, Bernhard (2018-10-01). "Automatic index selection for large-scale datalog computation". Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment 12 (2): 141–153. doi:10.14778/3282495.3282500. ISSN 2150-8097. https://doi.org/10.14778/3282495.3282500.

- ↑ Antoniadis, Tony; Triantafyllou, Konstantinos; Smaragdakis, Yannis (2017-06-18). "Porting doop to Soufflé". Proceedings of the 6th ACM SIGPLAN International Workshop on State of the Art in Program Analysis. SOAP 2017. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 25–30. doi:10.1145/3088515.3088522. ISBN 978-1-4503-5072-3. https://doi.org/10.1145/3088515.3088522. "The LogicBlox engine performs full query optimization."

- ↑ Arch, Samuel; Hu, Xiaowen; Zhao, David; Subotić, Pavle; Scholz, Bernhard (2022). "Building a Join Optimizer for Soufflé". in Villanueva, Alicia (in en). Logic-Based Program Synthesis and Transformation. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 13474. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 83–102. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-16767-6_5. ISBN 978-3-031-16767-6. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-16767-6_5.

- ↑ Nappa, Patrick; Zhao, David; Subotic, Pavle; Scholz, Bernhard (2019). "Fast Parallel Equivalence Relations in a Datalog Compiler". 2019 28th International Conference on Parallel Architectures and Compilation Techniques (PACT). pp. 82–96. doi:10.1109/PACT.2019.00015. ISBN 978-1-7281-3613-4. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8891656. Retrieved 2023-11-28.

- ↑ Jordan, Herbert; Subotić, Pavle; Zhao, David; Scholz, Bernhard (2019-02-17). "Brie: A Specialized Trie for Concurrent Datalog". Proceedings of the 10th International Workshop on Programming Models and Applications for Multicores and Manycores. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 31–40. doi:10.1145/3303084.3309490. ISBN 978-1-4503-6290-0. https://doi.org/10.1145/3303084.3309490.

- ↑ Whaley, John; Avots, Dzintars; Carbin, Michael; Lam, Monica S. (2005). "Using Datalog with Binary Decision Diagrams for Program Analysis". in Yi, Kwangkeun (in en). Programming Languages and Systems. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 3780. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 97–118. doi:10.1007/11575467_8. ISBN 978-3-540-32247-4. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/11575467_8.

- ↑ Hoder, Kryštof; Bjørner, Nikolaj; de Moura, Leonardo (2011). "μZ– an Efficient Engine for Fixed Points with Constraints". in Gopalakrishnan, Ganesh; Qadeer, Shaz (in en). Computer Aided Verification. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 6806. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 457–462. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-22110-1_36. ISBN 978-3-642-22110-1. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-22110-1_36.

- ↑ Fan, Zhiwei; Zhu, Jianqiao; Zhang, Zuyu; Albarghouthi, Aws; Koutris, Paraschos; Patel, Jignesh (2018-12-10). "Scaling-Up In-Memory Datalog Processing: Observations and Techniques". arXiv:1812.03975 [cs.DB].

- ↑ Shovon, Ahmedur Rahman; Dyken, Landon Richard; Green, Oded; Gilray, Thomas; Kumar, Sidharth (November 2022). "Accelerating Datalog applications with cuDF". 2022 IEEE/ACM Workshop on Irregular Applications: Architectures and Algorithms (IA3). IEEE. pp. 41–45. doi:10.1109/IA356718.2022.00012. ISBN 978-1-6654-7506-8. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10027548.

- ↑ Jordan, Herbert; Subotić, Pavle; Zhao, David; Scholz, Bernhard (2019-02-16). "A specialized B-tree for concurrent datalog evaluation". Proceedings of the 24th Symposium on Principles and Practice of Parallel Programming. PPoPP '19. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 327–339. doi:10.1145/3293883.3295719. ISBN 978-1-4503-6225-2. https://doi.org/10.1145/3293883.3295719.

- ↑ Wu, Jiacheng; Wang, Jin; Zaniolo, Carlo (2022-06-11). "Optimizing Parallel Recursive Datalog Evaluation on Multicore Machines". Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Management of Data. SIGMOD '22. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 1433–1446. doi:10.1145/3514221.3517853. ISBN 978-1-4503-9249-5. https://doi.org/10.1145/3514221.3517853. "These approaches implement the idea of parallel bottom-up evaluation by splitting the tables into disjoint partitions via discriminating functions, such as hashing, where each partition is then mapped to one of the parallel workers. After each iteration, workers coordinate with each other to exchange newly generated tuples where necessary.

- ↑ Shaw, Marianne; Koutris, Paraschos; Howe, Bill; Suciu, Dan (2012). "Optimizing Large-Scale Semi-Naïve Datalog Evaluation in Hadoop". in Barceló, Pablo; Pichler, Reinhard (in en). Datalog in Academia and Industry. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 7494. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 165–176. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-32925-8_17. ISBN 978-3-642-32925-8. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-32925-8_17.

- ↑ Shkapsky, Alexander; Yang, Mohan; Interlandi, Matteo; Chiu, Hsuan; Condie, Tyson; Zaniolo, Carlo (2016-06-14). "Big Data Analytics with Datalog Queries on Spark". Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Management of Data. SIGMOD '16. 2016. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 1135–1149. doi:10.1145/2882903.2915229. ISBN 978-1-4503-3531-7. https://doi.org/10.1145/2882903.2915229.

- ↑ Balbin, I.; Port, G. S.; Ramamohanarao, K.; Meenakshi, K. (1991-10-01). "Efficient bottom-up computation of queries on stratified databases" (in en). The Journal of Logic Programming 11 (3): 295–344. doi:10.1016/0743-1066(91)90030-S. ISSN 0743-1066. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0743-1066%2891%2990030-S.

- ↑ Ullman, J. D. (1989-03-29). "Bottom-up beats top-down for datalog". Proceedings of the eighth ACM SIGACT-SIGMOD-SIGART symposium on Principles of database systems - PODS '89. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 140–149. doi:10.1145/73721.73736. ISBN 978-0-89791-308-9. https://doi.org/10.1145/73721.73736.

- ↑ Dantsin, Evgeny; Eiter, Thomas; Gottlob, Georg; Voronkov, Andrei (2001-09-01). "Complexity and expressive power of logic programming". ACM Computing Surveys 33 (3): 374–425. doi:10.1145/502807.502810. ISSN 0360-0300. https://doi.org/10.1145/502807.502810.

- ↑ Bembenek, Aaron; Greenberg, Michael; Chong, Stephen (2023-01-11). "From SMT to ASP: Solver-Based Approaches to Solving Datalog Synthesis-as-Rule-Selection Problems". Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages 7 (POPL): 7:185–7:217. doi:10.1145/3571200. https://doi.org/10.1145/3571200.

- ↑ Zaniolo, Carlo; Yang, Mohan; Das, Ariyam; Shkapsky, Alexander; Condie, Tyson; Interlandi, Matteo (September 2017). "Fixpoint semantics and optimization of recursive Datalog programs with aggregates*" (in en). Theory and Practice of Logic Programming 17 (5–6): 1048–1065. doi:10.1017/S1471068417000436. ISSN 1471-0684. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/theory-and-practice-of-logic-programming/article/abs/fixpoint-semantics-and-optimization-of-recursive-datalog-programs-with-aggregates/605FE14CADEA2567C9EDBB78BBD1E0A2.

- ↑ "Chapter 7. Rules - LogicBlox 3.10 Reference Manual". https://developer.logicblox.com/content/docs/core-reference/webhelp/rules.html#rules-aggregation.

- ↑ "6.4. Negation - LogicBlox 3.10 Reference Manual". https://developer.logicblox.com/content/docs/core-reference/webhelp/formula-negation.html. "Additionally, negation is only allowed when the platform can determine a way to stratify all rules and constraints that use negation."

- ↑ "Datalog". SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY, department of Computer Science. http://www.cs.sjsu.edu/faculty/lee/cs157/24SpDatalog.ppt.

- ↑ Hillebrand, Gerd G; Kanellakis, Paris C; Mairson, Harry G; Vardi, Moshe Y (1995-11-01). "Undecidable boundedness problems for datalog programs" (in en). The Journal of Logic Programming 25 (2): 163–190. doi:10.1016/0743-1066(95)00051-K. ISSN 0743-1066.

- ↑ Lifschitz, Vladimir. "Foundations of logic programming." Principles of knowledge representation 3 (1996): 69-127. "The expressive possibilities of [Datalog] are much too limited for meaningful applications to knowledge representation."

- ↑ Huang, Green, and Loo, "Datalog and Emerging applications", SIGMOD 2011, UC Davis, http://www.cs.ucdavis.edu/~green/papers/sigmod906t-huang.pdf.

- ↑ Mei, Hongyuan; Qin, Guanghui; Xu, Minjie; Eisner, Jason (2020). "Neural Datalog Through Time: Informed Temporal Modeling via Logical Specification". Proceedings of ICML 2020.

- ↑ Chin, Brian; Dincklage, Daniel von; Ercegovac, Vuk; Hawkins, Peter; Miller, Mark S.; Och, Franz; Olston, Christopher; Pereira, Fernando (2015). "Yedalog: Exploring Knowledge at Scale". in Ball, Thomas; Bodik, Rastislav; Krishnamurthi, Shriram et al.. 1st Summit on Advances in Programming Languages (SNAPL 2015). 32. Dagstuhl, Germany: Schloss Dagstuhl–Leibniz-Zentrum fuer Informatik. pp. 63–78. doi:10.4230/LIPIcs.SNAPL.2015.63. ISBN 978-3-939897-80-4. http://drops.dagstuhl.de/opus/volltexte/2015/5017.

- ↑ Whaley, John; Avots, Dzintars; Carbin, Michael; Lam, Monica S. (2005). "Using Datalog with Binary Decision Diagrams for Program Analysis". in Yi, Kwangkeun (in en). Programming Languages and Systems. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 3780. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 97–118. doi:10.1007/11575467_8. ISBN 978-3-540-32247-4. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/11575467_8.

- ↑ Scholz, Bernhard; Jordan, Herbert; Subotić, Pavle; Westmann, Till (2016-03-17). "On fast large-scale program analysis in Datalog". Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Compiler Construction. CC 2016. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 196–206. doi:10.1145/2892208.2892226. ISBN 978-1-4503-4241-4. https://doi.org/10.1145/2892208.2892226.

- ↑ Antoniadis, Tony; Triantafyllou, Konstantinos; Smaragdakis, Yannis (2017-06-18). "Porting doop to Soufflé". Proceedings of the 6th ACM SIGPLAN International Workshop on State of the Art in Program Analysis. SOAP 2017. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 25–30. doi:10.1145/3088515.3088522. ISBN 978-1-4503-5072-3. https://doi.org/10.1145/3088515.3088522.

- ↑ Bembenek, Aaron; Greenberg, Michael; Chong, Stephen (2020-11-13). "Formulog: Datalog for SMT-based static analysis". Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages 4 (OOPSLA): 141:1–141:31. doi:10.1145/3428209. https://doi.org/10.1145/3428209.

- ↑ Madsen, Magnus; Yee, Ming-Ho; Lhoták, Ondřej (2016-06-02). "From Datalog to flix: a declarative language for fixed points on lattices". ACM SIGPLAN Notices 51 (6): 194–208. doi:10.1145/2980983.2908096. ISSN 0362-1340. https://doi.org/10.1145/2980983.2908096.

- ↑ Gryz; Guo; Liu; Zuzarte (2004). "Query sampling in DB2 Universal Database". Proceedings of the 2004 ACM SIGMOD international conference on Management of data - SIGMOD '04. pp. 839. doi:10.1145/1007568.1007664. ISBN 978-1581138597. http://dl.acm.org/ft_gateway.cfm?id=1007664&ftid=268727&dwn=1&CFID=411300798&CFTOKEN=23708243.

- ↑ Gallaire, Hervé; Minker, John 'Jack', eds. (1978), "Logic and Data Bases, Symposium on Logic and Data Bases, Centre d'études et de recherches de Toulouse, 1977", Advances in Data Base Theory, New York: Plenum Press, ISBN 978-0-306-40060-5, https://archive.org/details/logicdatabases0000symp.

- ↑ Abiteboul, Serge; Hull, Richard; Vianu, Victor (1995), Foundations of databases, Addison-Wesley, p. 305, ISBN 9780201537710, https://books.google.com/books?id=HN9QAAAAMAAJ&q=David+Maier.

References

- Ceri, S.; Gottlob, G.; Tanca, L. (March 1989). "What you always wanted to know about Datalog (and never dared to ask)". IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 1 (1): 146–166. doi:10.1109/69.43410. ISSN 1041-4347. https://www2.cs.sfu.ca/CourseCentral/721/jim/DatalogPaper.pdf.

- Abiteboul, S. (1995). Foundations of databases. Richard Hull, Victor Vianu. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-53771-0. OCLC 30546436. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/30546436.

|