Biology:Persistence hunting

Persistence hunting, also known as endurance hunting or long-distance hunting is a variant of pursuit predation in which a predator will bring down a prey item via indirect means, such as exhaustion, heat illness or injury.[1][2] Hunters of this type will typically display adaptions for distance running, such as longer legs,[3] temperature regulation,[4] and specialized cardiovascular systems.[5]

Some endurance hunters may prefer to injure prey in an ambush before the hunt and rely on tracking to find their quarry.

Humans and ancestors

Humans are some of the best long distance runners in the animal kingdom;[6] some hunter gatherer tribes practice this form of hunting into the modern era.[7][8][9] Homo sapiens have the proportionally longest legs of all known human species,[3][10][11] however all members of genus Homo have cursorial adaptions not seen in more arboreal hominids such as chimpanzees and orangutans.

Persistence hunting can be done by walking, but with a 30 to 74% lower rate of success than by running or intermittent running. Further while needing 10 to 30% less energy, it takes twice as long. Walking down prey, however, might have arisen in Homo erectus, preceding endurance running.[12]

Other mammals

Wolves,[13][14] dingoes,[15] and painted dogs are known for running large prey down over long distances. All three species will inflict bites in order to further weaken the animal over the course of the hunt. Canids will also pant when hot. This has the double effect of cooling the animal via the evaporation of saliva while also increasing the amount of oxygen absorbed by the lungs. Despite their similar body shape, other canids are opportunistic generalists that can be broadly categorized as pursuit predators.

Wolves may have been initially domesticated due to their similar hunting techniques to humans.[16][17] Several breeds of domestic dog have been bred with endurance in mind, such as the malamute, husky and Eskimo dog.

Spotted hyenas utilize a variety of hunting techniques depending on their chosen prey. They will occasionally use a similar strategy to canid endurance hunters, though their proportionally shorter legs makes this less effective.

Reptiles

No extant members of Archelosauria are known to be long-distance hunters, though various bird species may employ speedy pursuit predation. Living crocodilians and carnivorous turtles are specialized ambush predators and rarely if ever chase prey over great distances.

Within Squamata, varanid lizards possess a well developed ventricular septum that completely separates the pulmonary and systemic sides of the circulatory system during systole[5]—this unique heart structure allows varanids to run faster over longer distances than other lizards.[5] They also utilize a forked tongue to track injured prey over large distances after a failed ambush. Several monitor lizard species such as Komodo dragons also utilize venom to ensure the death of their prey.[18][19]

Extinct species

Little evidence exists for endurance hunting in extinct species, though potential candidates include the dire wolf Aenocyon dirus due to its similar body shape to modern grey wolves.

Non-avian theropod dinosaurs such as derived tyrannosauroids and troodontids display cursorial adaptions[20] which may have allowed for long-distance running. Derived theropods may have also had an avian style flow-through lung, allowing for highly efficient oxygen exchange.

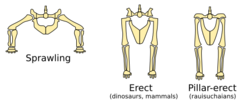

Some non-mammalian theriodonts may have been capable of running relatively long distances due to their limbs having an erect stance as opposed to the sprawling stance of contemporary synapsids and reptiles.

See also

- Hadza people

- Rarámuri people

- Tracking (hunting)

References

- ↑ Krantz, Grover S. (1968). "Brain size and hunting ability in earliest man.". Current Anthropology 9 (5): 450–451. doi:10.1086/200927.

- ↑ Carrier, David R. (August–October 1984). "The Energetic Paradox of Human Running and Hominid Evolution". Current Anthropology 25 (4): 483–95. doi:10.1086/203165.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Carretero, José-Miguel; Rodríguez, Laura; García-González, Rebeca; Arsuaga, Juan-Luis; Gómez-Olivencia, Asier; Lorenzo, Carlos; Bonmatí, Alejandro; Gracia, Ana et al. (February 2012). "Stature estimation from complete long bones in the Middle Pleistocene humans from the Sima de los Huesos, Sierra de Atapuerca (Spain)". Journal of Human Evolution 62 (2): 242–255. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.11.004. PMID 22196156. https://eprints.ucm.es/26998/1/1-s2.0-S0047248411002193-_01.pdf. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ↑ The evolution of sweat glands. Folk & Semken Jr. 1991. pp. 181.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Wang, Tobias; Altimiras, Jordi; Klein, Wilfried; Axelsson, Michael (December 2003). "Ventricular haemodynamics in Python molurus : separation of pulmonary and systemic pressures". Journal of Experimental Biology 206 (23): 4241–4245. doi:10.1242/jeb.00681. PMID 14581594.

- ↑ Bramble, Dennis M.; Lieberman, Daniel E. (November 2004). "Endurance running and the evolution of Homo". Nature 432 (7015): 345–352. doi:10.1038/nature03052. PMID 15549097. Bibcode: 2004Natur.432..345B. http://doc.rero.ch/record/15289/files/PAL_E2588.pdf. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ↑ Lieberman, Daniel E.; Bramble, Dennis M.; Raichlen, David A.; Shea, John J. (October 2007). "The evolution of endurance running and the tyranny of ethnography: A reply to Pickering and Bunn (2007)". Journal of Human Evolution 53 (4): 439–442. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.07.002. PMID 17767947. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:3743587. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ↑ Lieberman, Daniel E.; Mahaffey, Mickey; Cubesare Quimare, Silvino; Holowka, Nicholas B.; Wallace, Ian J.; Baggish, Aaron L. (2020-06-01). "Running in Tarahumara (Rarámuri) Culture: Persistence Hunting, Footracing, Dancing, Work, and the Fallacy of the Athletic Savage". Current Anthropology 61 (3): 356–379. doi:10.1086/708810.

- ↑ David Attenborough (25 August 2010). "The Intense 8 Hour Hunt". The Life of Mammals. BBC. Archived from the original on 31 January 2024. Retrieved 2023-05-10 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Stewart, J.R.; García-Rodríguez, O.; Knul, M.V.; Sewell, L.; Montgomery, H.; Thomas, M.G.; Diekmann, Y. (August 2019). "Palaeoecological and genetic evidence for Neanderthal power locomotion as an adaptation to a woodland environment". Quaternary Science Reviews 217: 310–315. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.12.023. Bibcode: 2019QSRv..217..310S. http://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/31956/14/Figure%204.pdf. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ↑ Trinkaus, Erik (1981). "Neanderthal limb proportions and cold adaptation". in Stringer, Chris. Aspects of Human Evolution. Taylor & Francis. pp. 187–224. ISBN 978-0-85066-209-2.

- ↑ Hora, Martin; Pontzer, Herman; Struška, Michal; Entin, Pauline; Sládek, Vladimír (2022). "Comparing walking and running in persistence hunting". Journal of Human Evolution 172: 103247. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2022.103247. ISSN 0047-2484. PMID 36152433.

- ↑ Mech; Smith; MacNulty (2015). Wolves on the Hunt: The Behavior of Wolves Hunting Wild Prey. University of Chicago Press. pp. 82–89. ISBN 978-0-226-25514-9.

- ↑ Thurber, J. M.; Peterson, R. O. (30 November 1993). "Effects of Population Density and Pack Size on the Foraging Ecology of Gray Wolves". Journal of Mammalogy 74 (4): 879–889. doi:10.2307/1382426.

- ↑ Corbett, L. K. (2001). The Dingo in Australia and Asia. J. B. Books. pp. 102–123. ISBN 978-1-876622-30-5.

- ↑ Larson, Greger; Bradley, Daniel G. (2014-01-16). "How Much Is That in Dog Years? The Advent of Canine Population Genomics". PLOS Genetics 10 (1): e1004093. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004093. ISSN 1553-7390. PMID 24453989.

- ↑ Frantz, Laurent A. F.; Bradley, Daniel G.; Larson, Greger; Orlando, Ludovic (August 2020). "Animal domestication in the era of ancient genomics". Nature Reviews Genetics 21 (8): 449–460. doi:10.1038/s41576-020-0225-0. PMID 32265525. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03030302/file/Bradley-v3-clean_1581526097_22_LAFF.pdf. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ↑ Fry, Bryan G.; Wroe, Stephen; Teeuwisse, Wouter; van Osch, Matthias J. P.; Moreno, Karen; Ingle, Janette; McHenry, Colin; Ferrara, Toni et al. (2009-06-02). "A central role for venom in predation by Varanus komodoensis (Komodo Dragon) and the extinct giant Varanus (Megalania) priscus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 (22): 8969–8974. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810883106. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 19451641. Bibcode: 2009PNAS..106.8969F.

- ↑ Fry, Bryan G.; Vidal, Nicolas; Norman, Janette A.; Vonk, Freek J.; Scheib, Holger; Ramjan, S. F. Ryan; Kuruppu, Sanjaya; Fung, Kim et al. (February 2006). "Early evolution of the venom system in lizards and snakes". Nature 439 (7076): 584–588. doi:10.1038/nature04328. PMID 16292255. Bibcode: 2006Natur.439..584F.

- ↑ Persons IV, W. Scott; Currie, Philip J. (2016-01-27). "An approach to scoring cursorial limb proportions in carnivorous dinosaurs and an attempt to account for allometry". Scientific Reports 6 (1): 19828. doi:10.1038/srep19828. ISSN 2045-2322. PMID 26813782. Bibcode: 2016NatSR...619828P.

|