Biography:Juan de Yciar

Juan de Yciar | |

|---|---|

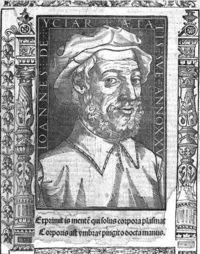

Engraving from his book | |

| Born | c. 1522–1523 probably Durango, Biscay, now Spain |

| Died | after 1572 probably Logroño, Crown of Castile, now Spain |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Calligraphy Mathematics |

Juan de Yciar or Iciar (16th century) was a calligraphist and mathematician active in Zaragoza in the middle of 16th century.

Life and work

Little is known about the life of Juan de Yciar and it is known by his self-explanations in the preface of one of his books.[1]

Born in Durango (north of actual Spain) c. 1523, he went to Zaragoza at a young age,[2] probably due to some familiar adverse circumstances.[3] When he was fifty years old, he was ordered priest and he was living in Logroño,[4] where it is supposed he was died sometime after 1573.

Yciar is known mainly by his work on calligraphy, edited first time in Zaragoza in 1548[5] titled Recopilacion subtilissima: intitulada Ortographia pratica: por la qual se enseña á escreuir perfectamente,[6] which was extended, modified and reedited many times, with different titles, during 16th century. It is a book to teach writing in which there are from pedagogic rules[7] to different types of letters,[8] going by formulas to make inks or ways to cut quills.[9] The success of the book resides in the fact that codification of a standard legible hand was indispensable to the functioning of an imperial bureaucracy that raising imperial Spain needed.[10] The plate engravings had been made by the French engraver Juan de Vingles, who worked in several Spanish towns during 16th century.[11] The editions of 1564 and onward had attached and annex on arithmetic written by Juan Gutiérrez de Gualda.

In 1549, and also in Zaragoza, he published a book on elementary arithmetic, with pedagogical goals, titled Arithmetica practica, muy util y provechoso para toda persona que quisiere ejercitar se en aprender a contar.[12][13] Despite the small success of this book, it is also a sample of the learning needs of the tradesmen in an era of growing of trade.[14]

References

- ↑ Echegaray Corta, pages 247–248.

- ↑ Madrid & Maz-Machado, page 118.

- ↑ Echegaray Corta, page 69.

- ↑ Echegaray Corta, page 150.

- ↑ Bohigas, page 209.

- ↑ Echegaray Corta, page 70.

- ↑ Echegaray Corta, pages 71–72.

- ↑ Echegaray Corta, pages 74–75 and 136–137.

- ↑ Echegaray Corta, page 73.

- ↑ Berenbeim, page 231.

- ↑ Bohigas, pages 225–226.

- ↑ Echegaray Corta, page 139.

- ↑ Madrid & Maz-Machado, page 117.

- ↑ Madrid & Maz-Machado, page 121.

Bibliography

- Barenbeim, Jessica (2010). "Script after print: Juan de Yciar and the art of writing". Word & Image 26 (3): 231–243. doi:10.1080/02666280903403276. ISSN 0266-6286.

- Bohigas i Balaguer, Pere (2001). "El libro español (Ensayo histórico)". in Antoni Badia Margarit. Mirall d'una llarga vida. A Pere Bohigas, centenari. Barcelona: Institut d'Estudis Catalans. pp. 21–366. ISBN 978-84-7283-556-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=7yLWMgiBz4kC.

- Echegaray Corta, Carmelo de (1907). "Calígrafos vascongados. Juan de Icíar" (in es). Revista Internacional de los Estudios Vascos = Revue Internationale des Études Basques 1 and 2: Vol.1: 242–248 and Vol.2: 68–75 and 136–150. http://www.euskomedia.org/analitica/1768.

- Madrid, Maria José; Maz-Machado, Alexander (2015). "Analysis of two Spanish arithmetic books written in the XVI century". Journal of Education, Psychology and Social Sciences 3 (2): 117–121. ISSN 1339-1488. http://www.sci-pub.com/archive/?vid=1&aid=3&kid=10302-7&q=f1.

- Maz-Machado, Alexander; López, Carmen; Sierra, Modesto (2013). "Fenomenología y representaciones en la Arithmetica Practica de Juan de Ycíar". in Rico, L. (in es). Investigación en Didáctica de la Matemática. Homenaje a Encarnación Castro. Granada: Editorial Comares. pp. 77–84. ISBN 978-84-9045-095-6. http://digibug.ugr.es/bitstream/10481/33497/1/23RodriguezMolina.pdf.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Juan de Yciar. |

- Turner, Eric Gardner. "Juan de Juan de Yciar". http://global.britannica.com/biography/Juan-de-Juan-de-Yciar.